The JobMaker scheme and FBT exemptions will play an important role in getting the Australian economy back on track. But HR needs to be at the forefront of these initiatives for them to have an impact.

The recent Budget announcement included some big promises for businesses with billions of dollars injected into education and training, and hiring incentives. While the opportunities presented will be a boon for economic recovery, using these schemes isn’t black and white.

HR professionals will play a critical role in helping their organisations navigate the nuances of some of the recent Budget items – such as ensuring training incentives are used effectively and that wage subsidies don’t derail workplace inclusion.

A lack of meaningful employment

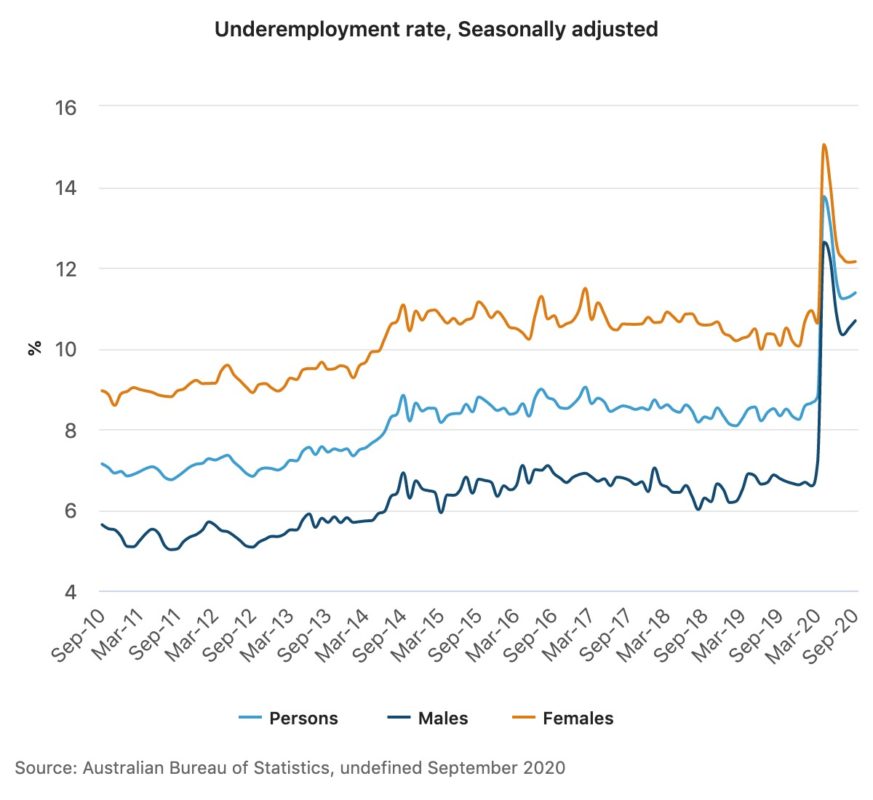

While the COVID-19 pandemic has seen a sharp rise in Australia’s unemployment rate, equally worrying is our current underemployment rate.

Underemployment encompasses quite a few different circumstances. It could mean:

- someone is employed but working less hours than desired

- someone is working in a low-income job

- someone is working in a role that doesn’t align with their skills and qualifications (i.e. a person with a law degree who is working part-time at a cafe)

When the Global Financial Crisis hit in 2007-2008, underemployment rates in Australia peaked at 5.9 per cent, according to ABS data. Fast forward to 2020 and that number has almost doubled – now sitting at 11.4 per cent.

Underemployment obviously has significant impacts on the economy, however, it’s also impacting individual wellbeing. Research shows that when people aren’t in meaningful employment (i.e. they’re underutilised) their mental health can suffer. In fact, 9 in 10 employees are actually willing to earn less money in order to contribute to society in a meaningful way.

Of course, each person’s definition of ‘meaningful work’ will differ. However, we can safely assume if someone – a recent graduate, for example – isn’t able to put their skills and years of study/training to the test, and instead has to settle for whatever they can find, that they might not experience high levels of career satisfaction.

The solution, of course, is creating more as well as appropriate jobs.

Unpacking JobMaker Hiring Credit plan

The Government is well aware of the fact that employment opportunities will be the lynchpin for recovery. That’s why it recently announced a $74 billion JobMaker plan designed to fast-track economic recovery and incentivise employers to increase hiring efforts.

Part of this hiring increase will come down to the $4 billion JobMaker Hiring Credit Plan. Employers that hire people aged 16-29 within the next 12 months will receive $200 per week towards that employee’s wages. New hires aged 30-35 will be subsidised with $100 per week.

The caveat here is that those hired need to have been receiving income support payments (JobSeeker, Youth Allowance or Parenting Payment) for at least three months prior to being hired.

To be eligible for this, employers must:

- hold an Australian Business number (ABN)

- be up-to-date with their tax lodgement obligations

- be registered for Pay As You Go (PAYG) withholding

- be reporting through Single touch payroll (STP).

On one side of the coin, this is a fantastic initiative. We know from previous research that young people were (and still are) disproportionately affected by the impacts of the GFC in terms of gaining meaningful employment opportunities in the preceding years. And getting more young people into the workforce will breathe some life into a crumbling economy.

However, this new scheme has a glaring obvious gap.

Mature age workers left behind?

“The fact that [this scheme] is discounting a huge portion of the older workforce is quite befuddling to me, ” says Denise Hanlon, principal at HR Hanlon.

“I read a lot of stuff about millennials and what they want from the workforce… but there’s a massive group of older (i.e. over 45 year olds) workers that are fit and well who have to earn a quid. They have a lot to offer.”

Ageism against older workers was already a problem prior to the pandemic. Australians aged 55 to 64 years old make up a significant proportion of our population (2.9 million) yet they face significant underemployment and unemployment rates and are often on the receiving end of all kinds of workplace discrimination and biases. Could the JobMaker scheme make this worse?

“We want more young people to join the workforce, yes. The more productivity and taxpayers, the more money there is to splash around. So I’m not saying they’re mutually exclusive. I’m just saying this particular initiative ignores a massive group of people who are already in the workforce and have amazing skills.

“There’s this massive group of people who want to continue to work but are invisible to a large degree.”

In response to criticism that the Budget is leaving out older workers, Prime Minister Scott Morrison said young workers are the most likely to lose their jobs during economic instability whereas those over 35 years will likely be able to utilise JobKeeper payments.

Hanlon is quick to point out that older workers aren’t without support. There’s the Restart scheme, she adds, which offers a $10,000 wage subsidy incentive (GST inclusive) for employers who hire and retain employees over 50, who work for at least 30 hours per week.

However, the worry is that because the Budget conversation is focussed on younger workers, that older employees, perhaps, could be unintentionally left behind.

“A lot of people in recruitment are fairly new to HR. It’s quite common for people to cut their teeth in HR by coming through the recruitment funnel,” says Hanlon. “So they’re perhaps not as aware of the value that older workers can bring to a role.”

Even if recruiters are consciously willing to give older candidates a foot in the door, unconscious bias and a tendency to hire those who are like us can mean that door is never really fully opened for older workers.

So while JobMaker is likely to answer a lot of our short term economic problems, it’s critical that HR professionals keep their eye on how this could potentially skew their organisation’s hiring preferences in the long term.

A win for employee upskilling

Creating jobs is one thing. Ensuring people are adequately prepared to fulfil the requirements is another.

Gartner recently surveyed more than 800 HR leaders about their 2021 priorities. Building critical skills and competencies came out on top as the most important priority (68 per cent of respondents felt this way).

In fact, Gartner’s experts predict that 33 per cent of the skills that were present in 2017 job ads won’t be necessary come 2021. While this research is US-based, the sentiment is echoed here in Australia.

The Budget announcement proposed a fix for this: resetting fringe benefit tax (FBT) for employee training – meaning employers no longer have to pay the 47 per cent FBT if they decide to offer training opportunities to employees.

This incentive aims to encourage employers to retrain and redeploy employees who may have otherwise faced redundancy. Even employees who have been made redundant can benefit.

To illustrate how this would work, the Government’s Budget breakdown document used the example of a retail company that was forced to close its doors of its store due to COVID-19. The owner wants to provide training opportunities to its ten staff members (worth $2,000 per person).

Five of these employees will use this training in order to become more attractive candidates for prospective employers. The other five will remain employed with the retail store and use the opportunity to upskill in web design to join the online team.

Without the FBT exemption, the employer would have had to fork out $17,735 in FBT to make this happen. During economically unstable times, this could deter the employer from going ahead with the retraining plan. However, under the new exemption plan the retail store won’t have to pay any FBT for these training programs.

Training and development opportunities are one way to upskill staff, but during a crisis it’s also worth doing a skills analysis of your workforce to see if there are complementary skill sets that could be used in other parts of your organisation.

In HRM’s previous article on HR’s role during a recession (written before we were actually in one), professor Wayne Cascio – a champion of responsible redundancy measures – said retraining employees, or finding new ways to utilise them, is crucial for survival in a recession.

He said employers should create what he refers to as ‘Leopard teams’ – meaning employees need to “change their spots” in order to add value and stimulate business recovery.

Cascio used the example of welding company Lincoln Electric, an organisation, he says, that hasn’t had to lay staff off since the 1930s. During the last recession, factory workers’ roles within the company were in jeopardy. Instead of cutting ties with employees, the organisation gave them the opportunity to find other ways to contribute to the business.

“One team identified a market for home welding equipment, and nobody was tapping into it. So they started working with big-box retailers and ultimately generated a US$800 million per year line of business,” says Cascio.

HR professionals need to help their organisations to think creatively in a crisis. Sure, Government incentives can give employers a much needed boost, but knowing how to make that boost go further requires strategic, long-term planning. That’s where HR’s influence and input is invaluable.

Need help navigating the people aspects of change management? This short course from AHRI will give you the tools and skills you need.