Unconscious biases that come from positive feelings (not negative feelings) can still be unfair, and might be more difficult to prevent.

Ageism against older workers isn’t what you might think it is. It would be wrong to conclude that everyone despises or even dislikes them. It turns out that, for the most part, older people are viewed as warm, trustworthy and friendly. The flipside is that they are also seen as incompetent.

Why these stereotypes persist and how they can be broken down are the subjects of research on unconscious bias that has important implications for workplace management.

The fact that ageism exists continues to be largely unacknowledged and is in stark contrast to other forms of discrimination, says Susan Fiske, Eugene Higgins professor of psychology and public affairs at Princeton University, who has been studying the topic.

“People don’t want to be called racist, but if you tell someone they are ageist, then no one gets defensive,” she says. “If you don’t realise you are biased against older people, there is no motivation to change your behaviour because you don’t feel shame.”

A standout finding in the research Fiske has led is that older people, and another discriminated group – people with disabilities – are well-liked, but also evoke pity.

And pity doesn’t get you the job. Or the promotion.

To explain why this happens, Fiske first makes a distinction between three types of unconscious bias. The first is an automatic response or ‘unexamined bias’, such as when an older person walks into an office and is automatically ignored. The second is ambiguity, which can be captured by the statement, “It’s not that I hate older people. It’s just that I like younger people, who are more like me, better.” The third response is ambivalence, and this is where pity comes in.

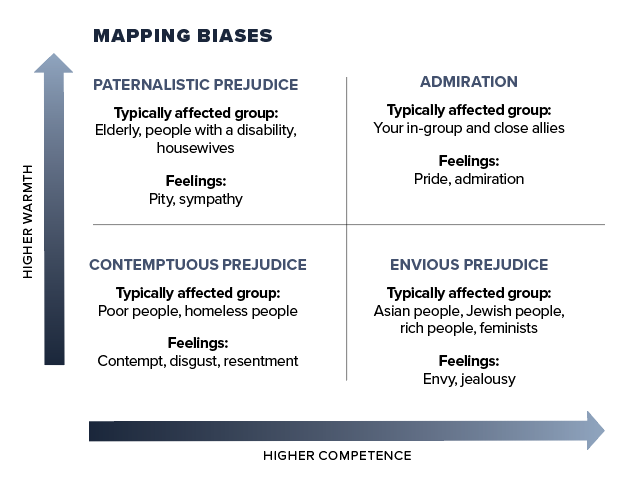

Older people and people with a disability rate highly for warmth and low for perceptions of competence. The prejudice typically felt towards them is therefore paternalistic.

So, on a personal level, some people may be fond of an older woman because she reminds them of their grandmother, but they wouldn’t want her running payroll.

“Older people are seen as well-intentioned but incompetent. It is a complicated form of discrimination both neglectful and demeaning, but also sympathetic. Our research found this is in contrast to groups that are seen as competent but cold, such as career women, rich people or politicians. These are people you have to go along with even if you would rather not.”

This one-day course from AHRI can equip you or your management team with techniques to reduce bias in your workplace.

Power dynamics

Status has an effect on all biases, including those rooted in sympathy. Media mogul Rupert Murdoch isn’t being ignored or pitied by anybody; the issue applies to older people in subordinate roles.

Where pity falls away is if an older person “gets uppity” or a person with disability becomes a rights advocate, says Fiske. Then they’re not pitied anymore and might even gain respect. “To get sympathy, you have to act in a certain way.”

To support their theory, Fiske and her fellow researchers explored several scenarios in which older people’s behaviour determined whether or not they were viewed sympathetically.

In a workplace setting, if an older person has power, such as the CEO, colleagues expect an orderly succession and that he or she should be open to retiring, willingly and gracefully.

“If you cooperate with succession, then people like you. If you don’t, people dislike you,” says Fiske.

“It’s not the same with a young or middle-aged person. They’re not expected to step aside.

“We found the same thing with consumption. If a company has options to take a lot of leave or flexibility and I use all my entitlements, then I’m putting a lot of burden on my colleagues. This is tolerated more in a younger and middle-aged person than it is in an older person.”

Another area where sympathy dissolved was when older people co-opted a younger identity. “We found that it’s not entertaining if young people go out for a drink after work and an old person tags along. Or if an old person tries to dance to young people’s music. There are very strong prescriptions for what old people should and shouldn’t do.”

Fiske and her colleagues have collaborated on equivalent Australian research, so these results are not peculiar to the US. They hold true the world over.

One of the biggest barriers to changing hearts and minds around ageism is the fact that old people are usually a part of everyone’s families. Fiske says it makes the biases “sticky”.

“If you are going to change your attitude, you have to change the way your family operates and really start respecting older people. It involves a certain relinquishing of power. Whereas if I change my attitude to Muslims, then it doesn’t have to impact my daily life,” says Fiske.

“People don’t want to be called racist, but if you tell someone they are ageist, then no one gets defensive.”

Ending bias

Generational tensions have always existed, but some people believe they are intensifying.

Michael North, Fiske’s PhD student and assistant professor of management and organisations at NYU Stern School of Business, says: “There is a perfect storm of generational tension factors. High youth unemployment, student debt and economic recession on one side, and dwindling respect for older people, limited job opportunities for older adults (particularly after a lay-off) and diminished retirement resources on the other.”

He’s speaking of a dynamic in the US, but it can be argued that it’s happening in Australia too.

Companies can play a very helpful role in ameliorating tensions and breaking down negative stereotypes about older workers. North says one way is to focus on the importance of ‘organisational memory’, which is held by those with a long tenure and tends to correlate strongly with chronological age.

“If you are a younger worker trying to forge your way at a company, very rarely does anyone make the effort, or have the ability, to spell out precisely how things get done, what the unwritten rules are and how the organisation fits into the industrial ecosystem. Knowing how to navigate the unwritten norms of the workplace is something that can help younger generations to value the wisdom, knowledge and experience of older workers.”

As an employer, you want to place staff where they are likely to be most successful and productive, and the same goes with older employees. In a study of best-practice for employing older workers in the US, North and colleagues found companies can help adjust to a rapidly ageing workforce by enacting four specific measures: flexible, half-retirement options; prioritising older-worker skills in hiring and promotion; creating new positions or adapting old ones to accommodate older employees; and changing workplace ergonomics. These are all visible signs that older workers are valued.

Training workers to recognise their unconscious biases is also key. Jill Noble, from Pivotal HR, has been running workshops on the subject in Australian organisations for five years and says no-one is immune.

“A lot of times the decisions made under the influence of unconscious bias are skewed,” says Noble. She cites a true story that went viral on social media, about a woman in Melbourne who had multiple sclerosis.

“She went to meet her daughter in a shopping centre and parked her car in a disability parking space. When she came back there was a note on the windscreen that read, ‘Did you forget your wheelchair?’ The person who wrote that may well describe him or herself as a disability rights activist. The point is, all is not what it seems to be. Selective perception is at work, and depending on what our brain chooses to see, that’s what we see.”

Noble believes we need to slow down and train our brains not to indulge in what she calls “thoughtless thinking”.

“Do I know the full facts? What am I not seeing? Questions like these help us move forward, to be less judgmental and make better, more balanced decisions.”

Noble has seen some progress with her clients. “One government department in Victoria regularly discusses unconscious bias in its team meetings and holds each other to account. There is responsibility at an individual level to continue exploring your own blind spot, and collectively, the organisation’s blind spots.

One way to become more aware of our biases and change our own actions is by taking people through the Implicit Association Test, says Noble. Developed at Harvard University in 1995, it measures a person’s strength of association between concepts and certain groups of people. For example, the association between clumsiness and people living with disability. Its purpose is to raise awareness, show people the extent of their biases and help them eliminate discriminatory behaviour.

Paying heed to Fiske’s research, it’s important to remember that sometimes those blind spots exist not because of our ignorance, indifference or hatred. Our compassion and sympathy can also disguise the truth.

This article originally appeared in the April 2020 edition of HRM magazine.

How great to see such evidence based material presented in such an easily understandable way. Well done Clive Hopkins and HRM.