Now that employees have had a taste of increased autonomy at work, employers that try to revert to their old approaches risk losing talent in the process. Instead, why not charge headfirst into a new way of working?

The pandemic has caused many employees to rethink their passions and set themselves up for new professional challenges, leading them to go searching for greener pastures. But in some cases, what’s causing employees to call it quits is the fact that their employer is no longer meeting their expectations.

Gone are the days of feeling grateful for simply having a job. Now, for many people, it’s all about having a job that delivers on a range of psychological, personal and professional needs. While this may seem unfair to some employers, it makes sense that we’re at this point.

In 2020, in a matter of months – days for some – employers and employees came together to devise new ways of working. This co-creation meant employers, whether they wanted to or not, had to take their hand off the wheel and let their people design solutions that worked for them.

“That relied on trusting employees to get the job done,” says Kerry Agiasotis, President of The Access Group, Asia Pacific, a business management software provider.

Research and anecdotal evidence tell us that productivity remained steady, or increased, when employees called the shots when working remotely.

“We all just want to be valued. The value doesn’t come from carrying out activities that someone prescribes,” says Agiasotis. “We’re all thinking people and we want freedom to make choices.”

Many leaders weren’t prepared for that shift. And plenty still aren’t.

“The pandemic resulted in panic on the part of many leaders,” says Doug Kirkpatrick, CEO at D’Artagnan Advisors, co-founder at Vibrancy and former Financial Controller at Morning Star.

“It’s why we saw an explosion in sales of spyware, for example, so people could be monitored more closely when they weren’t in the office.”

Even though this desire for autonomy is a by-product of the pandemic, it’s unlikely to wane as COVID-19 does, says Agiasotis.

“Once you’ve experienced something, and you know it works, it’s very difficult for employers to take that away. “Why would we go back to something that just isn’t as desirable as the current environment?”

Employers aren’t meeting autonomy expectations

In a recent report, The Access Group found that Australian employees’ appetite for more autonomous ways of working has increased since COVID-19, but employers aren’t necessarily meeting those needs. Employers were twice as likely to operate under a command-and-control approach than they were to offer autonomy.

“Nearly 70 per cent of the respondents said [autonomy] was now an expectation,” says Agiasotis. “We’re probably going to see a change in the way their organisations work as a result of this.”

The research showed employees want control in three main areas: where and when they work (this will be a universal expectation for office-based workers in 2022); the activities that are part of their work; and the resources they have access to.

“It’s not like you can just do your own thing and show up when you want. There’s a lot of structure in place to make it work.” – Carol Gill FCPHR, Associate Professor, Organisational Behaviour, Melbourne Business School

It also found that 35 per cent of organisations favoured forms of empowerment – for example, you can determine how to approach a task, but your boss will determine the task – over full-blown autonomy, which is what their people were actually calling for.

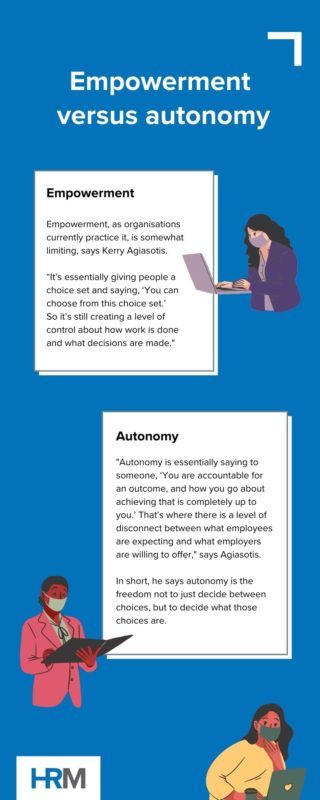

“There’s this disconnect in expectations, and even understanding, as to what empowerment is versus what autonomy is,” says Agiasotis. (See infographic below).

It’s important that employers understand and communicate the difference between the two, he adds.

“Without that level of understanding, an organisation thinks it’s doing what employees want, but it can give you the opposite effect, because employees look at that and think, ‘They don’t know what they’re doing.’”

Autonomy at work to the extreme

If you want a lesson in extreme autonomy practices, take a leaf from Chris Rufer’s book. In the 1970s, he spent his summers driving a truck delivering tomatoes in California. A lot of the companies he was visiting were antiquated and inefficient, he thought, so he started investigating where the bottlenecks were by talking to the workers at the various factories.

Over the next decade, he used this information to develop a business theory for his own tomato processing company.

“I joined him in the early 1980s as the financial controller,” says Kirkpatrick. “We started with a small team of 24 people, working out of a tiny farmhouse.”

Over the years, the business evolved into Morning Star, the world’s largest producer of tomato products. It now employs more than 400 full-time workers, with an additional 2500 seasonal workers, all of whom work completely autonomously.

“Everyone is considered a professional. There’s no blue-collar versus white-collar – there’s no collar. The people who clean the bathrooms are considered professionals, and their voices are respected because everyone’s voice is equal.

“[They’re all] making gigantic, life-changing decisions about who to marry, what to do for a living, whether to buy a car or house, or have kids. Somehow they made these decisions without a boss. So logically, if people know what to do at work and how to do it, why do they need a boss at all?”

A lot of people would be able to come up with a few reasons: to maintain order, to outline a future direction, to ensure nothing slips through the cracks, or to determine important decisions such as pay, consequences for poor performance or who to hire.

But Kirkpatrick insists there’s no need for a chain of command in these situations.

At Morning Star, if you want a raise, you’re welcome to determine that yourself. If you present a compelling enough business case to a panel of your colleagues, it’s yours. If disagreements arise, there’s a plan for that, too.

“There’s a process called ‘gaining agreement’. If the two people can’t agree, a third colleague is brought in as the mediator. If that doesn’t work, the problem can be escalated to a group panel of colleagues.”

“[They’re all] making gigantic, life-changing decisions about who to marry, what to do for a living… Somehow they made these decisions without a boss. So logically, if people know what to do at work and how to do it, why do they need a boss at all?” –Doug Kirkpatrick, former financial controller at Morning Star

In very rare circumstances, unresolved matters will be elevated to Rufer, who remains the company’s President, for a binding decision. So some processes do require a light touch of hierarchy.

Also, if someone is underperforming, or simply isn’t the right fit, anyone in the company can ask them to leave.

“Everything is accomplished by request and response. So anyone can ask anyone to exit the company. But it’s a request; no one has command authority. People are free to respond in whatever way makes sense for them.

“We’ve had people who were asked to leave who said, ‘Yeah, you’re right. I should leave.’ And if people disagree, that’s where the gaining agreement process comes in.”

All hiring decisions are made in consultation with any employee who will be impacted.

“We would never hire an industrial electrician, for example, without having every other industrial electrician vet that individual for their capacity and aptitude.”

How can you maintain order?

At this stage, you might be thinking, ‘That all sounds well and good, but how practical is it in reality?’

In Morning Star’s case, it was about setting boundaries early on. Rufer first proposed the idea of a self-managed organisation before the first factory began operation. Everyone gathered in a trailer to discuss how they’d govern the organisation.

“[Rufer] handed out a document called the Morning Star team principles. Basically, they boiled down to two things: people shouldn’t use force or coercion against other human beings… and people should keep the commitments they make to each other, or renegotiate the commitment.

“When we filed out of the trailer, we became a self-managed enterprise. On 16 July 1990, we turned on the factory and produced 45 million kilograms of industrial tomato concentrate for the world market. And we did it without a single boss, supervisor or manager – there was zero command authority, just humans working as a team.”

Six years later, after Morning Star had built and operated its second factory, the company developed an instrument called a Colleague Letter of Understanding (CLOU) to prevent processes from descending into chaos and to coordinate activities.

“[The CLOU] includes details of the who, what, why, when, where and how of work, with some verbiage about being careful with proprietary information, expectations for hours of work, short-term and long-term goals, and alignment with the mission of the enterprise. People negotiate, review, and then sign it. They take it very seriously.”

Defining the challenges

Research tells us that autonomy is a great way to motivate people and see their productivity and moods improve. And while Morning Star is a great success story, there are plenty of examples of autonomy-at-scale failing, says Carol Gill FCPHR, Associate Professor of Organisational Behaviour at Melbourne Business School.

“In principle, autonomy is great. We know it’s a high-performing practice. But in reality, it requires calibration to make it work effectively,” she says.

For instance, there can be issues with alignment to other teams and the organisation’s goals. People get too caught up in their own world to work towards the bigger picture. Also, we all have different growth needs, she says.

“Some people will just want different work rhythms – they want time off to go to the doctor, for example, or [spend time with their] families at home – but that’s as much as they want. They’re not seeking decision-making power.”

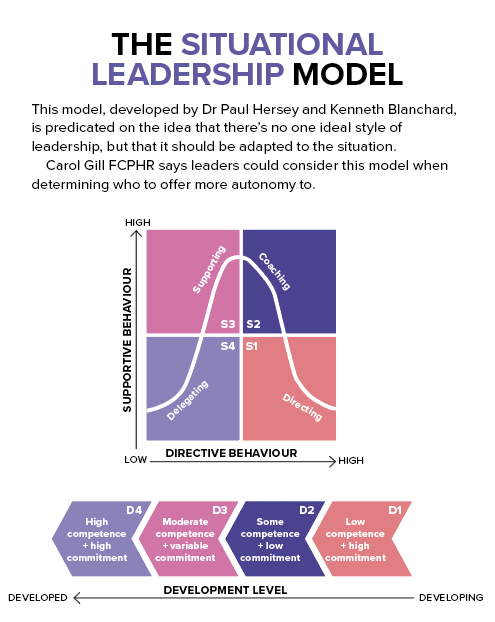

One factor that often determines this is a person’s seniority or experience, she says.

“The Situational Leadership Model, based on the contingency theory of leadership [see illustration], suggests if somebody is quite junior and new to a job, you have to give them a lot of intense direction. But if somebody is fully capable and highly motivated, you leave them alone.

It comes down to the manager to determine how much autonomy could be offered.”

Importantly, we need to do away with the idea that autonomy means a free-for-all, says Gill. Successful autonomous processes must have structure and be aligned with culture.

“If you think of agile work, those organisations often have a matrix structure where you report through to somebody who manages your performance and allocates you to different projects. Then you might also report to a project leader. Accountability is significant. It’s not like you can just do your own thing and show up when you want. There’s a lot of structure in place to make it work.”

Also, autonomous organisations can run on peer control, which Gill says can be “far more oppressive than any [formal] management structure”.

People are often quick to pull their co-workers up for slacking off, for instance, because that could mean everyone misses out on a bonus.

“That can even come down to something like the chairs they buy. If they buy expensive ones, that reduces the profit margin that all team members get. In those organisations, you think it’s hands-off leadership, but power has just been transferred to peers, and they [can be] very harsh on each other.”

How much employee autonomy should you offer?

The question of ‘How much autonomy should we offer?’ depends on your culture and goals.

Whatever you do, it’s critical that you don’t exclude employees from the conversation, says Agiasotis.

“Engage colleagues through that conversation. It’s important to do that because they’ll tell you what they expect and the freedoms they’d like.”

Outside of offering employees autonomy over where they work, which most companies would already be doing, you can also think about giving them more control over idea generation, he says.

“There’s so much tacit knowledge in the employee community. Engage them in ideation. That’s a simple way to demonstrate that their contribution is valued beyond carrying out structured work.”

You also need to apply a congruence model to all processes, says Gill, because while your employees might be happy with autonomous working, perhaps your customers are dissatisfied.

“Or some people are working really hard while others are at home having a lifestyle,” she says.

Gill notes that new processes need to be assessed on three levels: individual, group and organisational.

“The organisation might set up structures for full-level autonomy, but at the group level, that may vary. Think of people who are in accounting; they can work from home. But what about the maintenance people – the people screwing things into walls. They’re not going to have the same autonomy, so you need variation at a group level.”

That variation could look like offering decision-making power, says Kirkpatrick.

That might involve small things at first – “What coffee should we order?” or “What colour should we paint the walls?” – but eventually you might start asking bigger questions like, “What should our operating hours be?”or “What kind of clients would we never work with, and why?”

“When you start distributing decision-making authority to the edges of the organisation, that can be magical in terms of waking up engagement, responsibility and accountability,” says Kirkpatrick. “When people own decisions that they didn’t previously own, they suddenly get very serious and focused on their work.”

Preparing your culture

To prime your culture for more autonomous styles of working, you need to introduce the right training, says Gill.

“Not just in the hard skills, but the ‘soft’ skills, too. How do I work with others? How do I take initiative? How do I check in? How do I take responsibility and find out what’s going on?

“You also have to pass information down to everybody and let them know what the organisation’s direction currently is. That [information] is often determined by folks who are in strategic areas of the business, but it has to be pushed down to the frontline.”

Gill argues that, prior to COVID-19, many businesses were run on lazy management.

“Employees clocked in and out, employers checked they had bums on seats, and that was it. An autonomous approach to work requires leadership that’s capable of thinking outside the box in terms of creating systems that allow people to thrive.

“Think of IT, for instance. They’d roll their eyes at a conversation like this because they’ve been doing it for years,” says Gill. “They run on a ticketing system. That’s the way it’s got to move for everyone. Otherwise you might try to contact someone whose working hours are 8pm to midnight every day, but I’m putting in a request at 8am for a customer who needs an immediate answer. We’ve got to have more tech to help us distribute work to everyone.”

Another way to offer more autonomy is to simply give people more information, says Kirkpatrick.

“When we put graphs on the wall showing trend lines of performance improvement, or efficiency over time, people paid attention to those things. People were able to gamify their roles and figure out how to play the game of work in an enthusing way, without a boss telling them if they’re doing a good job.”

For those looking to trial more autonomy, one challenge could be getting leadership buy-in. To this, Agiasotis says think about what people have experienced in terms of new-found autonomy, and what you’d be taking away.

“You’ve already introduced autonomy to the business. If things are working, even if they need to be tweaked, look for those opportunities for improvement rather than reverting back to the previous state.”

Asking leaders to willingly relinquish power is a big ask, says Kirkpatrick.

“But they should feel anxious about what happens if they don’t do it. Because companies that don’t figure out how to make these shifts in the uncertain world in which we live in will be outperformed by organisations that figure out how to build robust, dynamic, networked organisations.”

A version of this article was first published in the February 2022 edition of HRM Magazine.

Gain the leadership skills you need to help your organisation navigate change with this short course from AHRI.