Could your organisation survive without its managers? Some companies already are. HRM takes a deep dive into flat organisations.

There’s a company in America called Morning Star. It permanently employs around 600 people and adds another 4000 to the books for seasonal work. It’s a tomato processing factory and has the largest production scale of tomato-based products in the world, but that’s not the only thing that makes it unique.

It also decided to eliminate all of its managers.

If you’re a manager, you’ll be no stranger to the time-sucking responsibilities that often go into your role. That’s why some call management the least efficient, most costly function of a business.

However, there’s an equally important argument to be made for the importance of middle management – these people coach and develop your star players, they handle the inevitable disputes that arise, they set boundaries and expectations, and they ensure the wheels keep turning.

So could you really operate without them?

Only got time to skim? We’ve included some quick tips at the bottom of this article.

Will flat organisations rise in 2021?

When done successfully, flat organisations can become a key pillar of an agile workforce. With ‘agility’ being a buzzword many equate with business success post-pandemic, could we see more flat organisations cropping up in the near future?

Dr Nidthida Lin, senior lecturer, department of management at Macquarie Business School, can see it going two ways.

“With the rise in remote work, I can see some organisations imposing more hierarchy as they try to monitor the work their people are doing [at home],” says Lin.

“However, I can also see a group of organisations becoming flatter as a way to increase speed and responsiveness to a changing environment… so you don’t have to go through so many layers of approval; you can just make things happen. Another reason to become flatter [post-pandemic] would be to reduce costs.”

However, there’s more than one way to be agile and reduce costs, and Lin warns against jumping on the bandwagon.

“You need to ask what you’re trying to achieve by being flat. Do you need to be more responsive? Do you need to be faster? If you work in a highly dynamic industry, it might be something that suits you. If you operate in a relatively stable environment… the cons will probably outweigh the pros.”

“You want to be agile because it’s a catchy term and everyone is doing it, but one pitfall of [flat organisations] is that people jump in before assessing if they are ready, or if they really need it.”

The benefits of cutting out the middleman

Proponents of flat organisations will tell you removing layers within an organisation allows ideas to permeate; you’re getting rid of unnecessary approval layers and allowing employees more autonomy, therefore boosting their engagement and, potentially, their wellbeing too.

Hierarchical structures can also suppress innovative ideas.

When Lin studied flat organisations, she spoke with leaders who were in favour of trimming the management fat. One executive told her he was worried that he was being presented with ideas that had been through a filter – ideas that were most likely to get funded. But he wanted to see the first drafts, the big ideas, the fruits of a brainstorming session. That’s where he believed a lot of creativity and innovation was hiding.

“I was looking into the cognitive biases that occur when managers make a decision. A lot of the time when you make decisions based on a hierarchy of people that need to approve it, the KPIs will be set around profit and revenue. That can be a real killer of innovation because [the manager] has a specific idea in mind about how they’re going to judge an idea.

“It means they’re only thinking about how to serve their mainstream customer, but that doesn’t open up new markets for you.”

There’s a reason some big companies carve out time for employees to think outside the box – that’s how we ended up with Gmail, Twitter and Slack, or so the legends suggest.

“We need more leaders. Not managers.” – Jocelyn Hunter, founder of BENCH PR.

The most obvious benefit of a flat organisation is the time it gives back to workers.

Jocelyn Hunter, founder of BENCH PR, worked in a flat organisation in the UK. She loved it so much she decided to introduce the idea to her own company back in Australia, which she founded in 2008.

“My experience of working in other PR agencies is that the more senior you get, the less PR you actually do. You’re hamstrung to an office and you spend your time managing people and budgets,” says Hunter.

“A flat structure enables you to get on with the job. It removes time required in meetings, the chain of emails for ‘approval’ [and it] enables flexibility. You also build deeper relationships with your clients because you have to be across everything.”

Hunter notes it’s not for everyone and admits she has struggled to find and retain the “team players” needed to make a structure like this succeed.

“It works well if you want to keep your team small and specialist, like we are. [There are] no junior staff to train or manage, just experienced people who are great at what they do.”

Interested in upping your workforce management game? AHRI has a short course on this very topic. Book your spot for the next session on 17 June 2021.

No chain of command

Others argue that a lack of a clear hierarchical structure could actually add a level of complexity as employees might struggle to know where responsibilities lie and who needs what information.

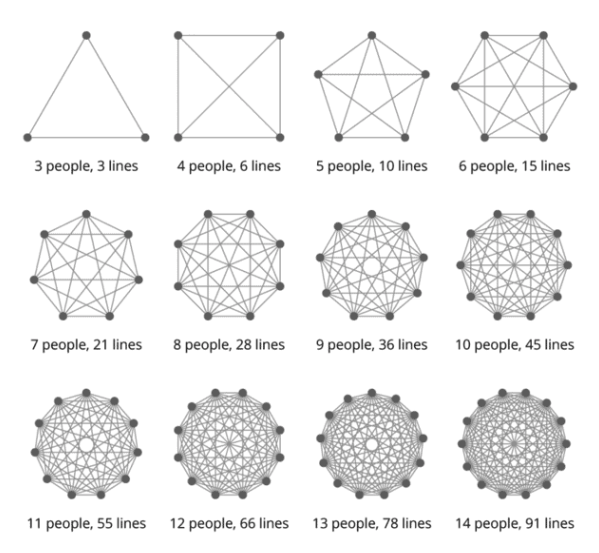

This only gets trickier when more people are layered into the organisation.

In 2015, Chris Savage – founder of US-based video marketing agency Wistia – decided to pull the plug on his flat structure because he found it wasn’t conducive to growth. The idea of a flat structure excited him at first. He said it was “startup-y and awesome” in a blog post, however, it soon turned into the company’s “biggest weakness”.

“It became hard to take risks – no one was clear on who was responsible for what. We moved more slowly, and it felt harder to learn and be creative,” wrote Savage.

“We had centralised all the decision-making…. If you don’t explicitly define your structure, then you are left with an implicit one, and that can stifle productivity. We had hoped that being flat would let us move faster and be more creative, but as we grew, we ended up with an unspoken hierarchy that actually slowed down our ability to execute.”

But Morning Star was able to make it work, so what’s its secret? Making sure that even though management was absent, leadership was not.

As a group, they would agree upon who the right person was to lead a specific project and that person would be granted temporary authority. They also had a lot of other structural elements in place to ensure responsibility and accountability was present at every turn (see tips at the end of this article).

It’s also worth considering what cutting out the middleman will do to employee motivation. We’re not all driven by the same incentives. Some of us are intrinsically motivated, others are extrinsically motivated. The latter group could suffer in a flat organisation.

“If you’re changing your structure, you also need to change your rewards system,” says Lin. “Your performance management systems have to reward the habits of a good leader, not just looking at if a project was finished and within budget, but also how much effort someone put into [developing] the people in their team, or coaching or providing feedback to someone.”

You would also need to assess your remuneration strategy, Lin adds, as people who might have usually progressed to management as a way to get a salary bump might still need financial motivation to stay with your company.

To remedy this, Lin says “you might introduce specialist streams instead of management streams”.

The struggle of being your own boss

Lack of accountability and motivation are just two challenges to overcome. There are plenty more.

Skills development opportunities could fall to the wayside, for example, as people focus on their own patch, and with no one calling the shots, it can also be easy for pseudo-managers to come to the fore; you end up with too many cooks in the kitchen and not enough meals getting made.

It’s also challenging to push against the traditional approaches embedded within an organisation. Many people categorise flat organisations as the domain of small businesses or start-ups that are setting the cultural tone from scratch.

“If you are a more established firm or an organisation that is really large, it’s difficult to successfully transform your organisation to be flat,” says Lin.

It’s challenging because big companies have to change the mindset of all of their people, says Lin, and the former managers need to understand that giving up power and formal authority doesn’t necessarily mean they are giving up their influence.

“When you look at flat organisations that went back to being more hierarchical, it’s almost always because they wanted to take back control,” she adds.

This isn’t to say it’s impossible for larger companies, it will just take longer. Lin was speaking with a large Australian supermarket chain that was trialling a flat organisation and while there were speed bumps it gained important lessons before committing to a new structure.

“It is notorious for having too many levels of hierarchy and it wants to go flat, but it knows it can’t do it in one go. It has started by implementing it for a smaller part of the business and has been trialing it for almost a year now, but it’s still not ready to roll it out across the entire organisation.”

The supermarket found that the flat teams increased internal politics.

“Some people didn’t get along with the people in their teams and they didn’t have a manager who they could raise their problems with.”

“It means they’re only thinking about how to serve their mainstream customer, but that doesn’t open up new markets for you.” – Dr Nidthida Lin, senior lecturer, department of management at Macquarie Business School

Lin suggests adopting a flat organisation model only where it makes sense, such as a department that might need to be responsive to a changing market or generate innovative ideas, and have other departments retain that traditional hierarchy.

She adds that you can also have varying degrees of ‘flatness’. You might be very flat (C-Suite/founder only – like Morning star) or you might have one layer of managers but remove individual team leaders, for example.

As is the case with all the other innovative ways to work – remote work or the four-day week, for example – it will only succeed if trust is put front and centre.

In nearly 13 years of working flat, Hunter says she’s never had any issues with accountability because she makes it clear that trust is of utmost importance.

“Not everyone I’ve hired has worked out. There are some people who have joined that only want to do ‘part of the job’ and that just doesn’t work. You have to trust your team to do the job.

“I found this difficult, particularly in the early days, when you want to control and do everything yourself, but as you grow, you realise you can’t do this. There is nowhere to hide working in a flat structure; you’re accountable. And if you don’t trust your team to do the job, why have you hired them?

So, does all this mean that middle management will one day be redundant? Hunter thinks so.

“I think if you trust your team to do the job, and they do, why waste time and energy trying to ‘manage them’. We need more leaders. Not managers.”

Tips for trialing a flat organisation

- Lin suggests starting with one function of your organisation and learning from their approach.

- Develop a collective mission statement. Morning Star did this and it helped to give employees something to work towards.

- Consider creating a colleague letter of understanding (CLOU). Morning Star also did this and found it helped keep people accountable. The CLOU outlined each person’s commercial mission and their commitments to the company, which they had agreed upon with others.

- As a collective, create a set of guidelines for managing difficult situations – such as performance issues, conflict or needing to fire someone. That way, when one of these things occur (and they will), there’s a clear structure to follow. In some instances, you may need to elect a person to make the final call (usually the founder) but only if your collective processes aren’t working.

- Have a really solid change management and communication plan in place, says Lin, and remember these things can take years to get off the ground.

Want to hear more about Morning Star’s flat organisation? Listen to this episode of Adam Grant’s podcast, Work Life.