Leading thinkers on the future of work have given us their roadmap for the years to come, and it runs counter with the narrative some of us have told ourselves.

The CBD isn’t dying. Very few jobs are entirely automatable. And we should hold on tight to middle management.

Many delegates who attended the final day of AHRI’s TRANSFORM 2021 conference had to throw away everything they thought they knew about the future of work, as range of experts clarified where HR and workplace leaders should be focussing their attention.

This article will focus on some of the key insights from the day around the future of work (FoW), and we’ll be bringing you more from the day’s illustrious speakers over the coming weeks.

Want to skip to the part that interests you most? Here’s a look at what this article covers.

- Dr Daniel Susskind’s views on the automation of work (it’s about tasks, not entire jobs).

- Dr Ben Hamer’s helpful tips for future-proofing your business.

- Caitlin Guilfoyle’s quick tips to put Hamer and Susskind’s insights into action.

Here’s how you should actually think about automation

In the 1800s, London and New York faced what has since been called ‘The Great Manure Crisis’. Horse-drawn carriages were the cities’ main form of transport. In London alone, around 50,000 horses were utilised, each producing between 15-35 pounds of manure a day.

People were getting sick as the congregating flies spread typhoid and other diseases, and a 1894 article in The Times declared, ‘In 50 years, every street in London will be buried under nine feet of manure.’

Urban planners and policymakers were understandably concerned about what this would mean for the future of both cities. However, those fears were soon allayed with the development of the first combustion engine, followed by the introduction of automobiles.

This is the story Dr Daniel Susskind told to open his keynote address.

You might think this centuries-old anecdote was shared to demonstrate human ingenuity in the face of crisis, and that Susskind was using this to anchor what would be an inspirational speech about ‘anything being possible’ if only we’d be open to exploring the possibilities that technology has to offer.

But this wasn’t his point at all. Yes, that moment in history marked a turning point in our technological advancement, but it was also the moment we first gave up a sense of control to machines.

“If there’s one thing to take away from this is, it’s that in the medium term, the challenge is not one of mass unemployment, rather one of mass redeployment.” – Daniel Susskind

“In most retellings of this story, it’s cast in a relatively optimistic light – as a tale of technological triumph,” said Susskind, who is a Fellow in economics at Balliol College, Oxford University. “But for Wassily W. Leontief, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics for his research, this story led him to a far more unsettling conclusion.

“What he saw was how an animal that had played a central role in economic life for millennia, had been banished to the sidelines by technological change. And in a set of articles he wrote in the early 1980s, he expressed one of the most infamous claims in modern economic thought – that what cars and automobiles had been to horses, robots and computers would be to us.”

Susskind shares this anecdote not to scare us, but to prepare us because “we have to take the anxieties about technological change seriously”.

The digital engulfment of work is such a mammoth topic. Where to begin? Susskind suggests looking at our differing views of blue versus white-collar automation.

“Many people are very comfortable with the fact that technology might have a disruptive impact on the things blue-collar workers do; the farmers and factory workers,” said Susskind.

He demonstrated this with a graph showing that in 1860, nearly 27 per cent of the US workforce held roles in the agriculture industry. In 2000, that number fell to about 1.2 per cent, yet the output from the agriculture industry increased fivefold. Similar data was shown for the manufacturing industry.

Overtime, we’ve developed a comfort level with certain blue-collar roles being automated – that’s just how technological advancement works, we’d tell ourselves.

What’s less easy to swallow, however, is when AI creeps into the white-collar world.

“Why do we think white-collar workers are somehow immune from technological change? It seems to me that the answer is because we tend to think of the work that blue-collar workers do as being relatively routine, process-based and relatively straightforward to automate.”

It’s also worth noting some potential classist undertones at play, but that’s a story for another time.

Susskind suggests that we feel more threatened when robots do something we believe to be inherently human, such as creative, empathy-based work.

He went on to list the various white-collar roles that have recently been automated – the lawyers, the journalists (yikes), the architects, medical professionals and, would you believe it, the role of confessionals with a priest (yes, there’s even an app for that).

It was at this point that delegates started jokingly sharing commiserations with each other in the live discussion function of the virtual event platform. But Susskind was quick to clarify that this didn’t mean we were all doomed, just that some of us might be thinking about the future of work in the wrong way.

The challenges we’ll face around technologies are more mundane than Hollywood would lead us to believe, he said.

“If there’s one thing to take away from this is, it’s that in the medium term, the challenge is not one of mass unemployment, rather one of mass redeployment,” he said.

“It’s still a very significant challenge, but it’s quite a different challenge – equipping people to do the work that [needs] to be done, rather than there not being enough work.”

Another misconception many people hold about the FoW is that it’s about entire jobs, said Susskind.

“That’s unhelpful because it encourages us to think of the work that people do as a monolithic, indivisible lump of stuff, when actually, if you look under the bonnet of any job, what you see is a wide range of different tasks.

“The risks, when we think about the future of work in terms of entire jobs, is that we get trapped in a mindset where the only way that technological change could affect the work we’ll do is by destroying, or perhaps creating, jobs in an instant. But that isn’t what technological change does.

“What it does is far more gradual and [subtle]. It might displace people from certain tasks… but it can also make other tasks more valuable and important for human beings to perform,” he said.

If you’re looking for hard data to support this opinion, Susskind had some up his sleeve.

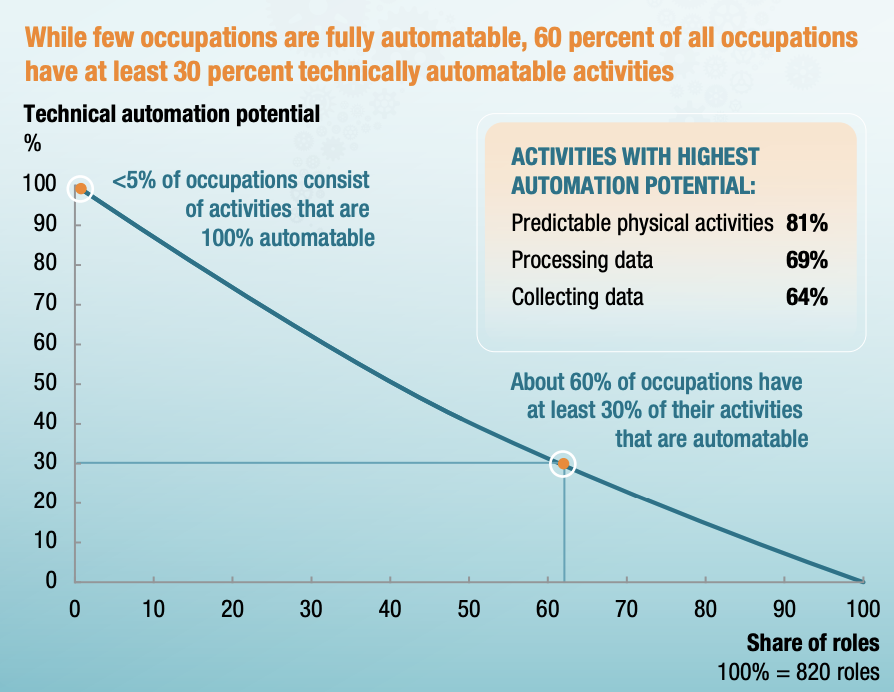

He pointed to 2017 research from McKinsey which showed that of 820 jobs in the US, only 5 per cent could be fully automated. This doesn’t align with the ‘robots are stealing our jobs’ narrative.

Interestingly though, the research also found that 60 per cent of those jobs involved tasks in which 30 per cent could be automated (see graph below).

“That’s the first reason why I think white-collar workers need to take this technological disruption more seriously.”

The second reason is a result of our current times. The pandemic has created more of a need to rely on automation because “a machine cannot catch the virus and fall ill”.

“It’s not going to take time off to protect co-workers or customers, or to recover. There is a new incentive to replace people with machines, and as we see more and more labour shortages, particularly in lower paid service roles, that incentive… is only going to get stronger.”

This is the point where you might let out a big sigh. But fear not, Susskind was kind enough to leave us with some hope. Our best response to this challenge is to rethink how we approach education, he said.

“We need to look at those tasks and activities that are hard to automate, those that are non-routine. In spite of everything I’ve said, of course there are large areas of human activity that remain out of reach of even the most capable machines.”

That’s the ‘what’ but equally important is the ‘how’, he adds.

“The ways in which we educate people hasn’t changed for centuries – traditional classroom settings with one person at the front and 10 to 30 people in the classroom being broadcasted to.”

We need to move away from that, he said. Would that involve more one-on-one training, for example? Or utilising technology to connect with global experts who we previously might not have had access to? It’s time to expand our thinking and try new approaches, he suggested.

Finally, Susskind said we need to address the ‘when’.

“There’s a cultural presumption that education is best done at the start of your life. That’s when you spend the time and money learning the skills and capabilities to prepare yourself for the world of work.

“But the best response to uncertainty is flexibility and willingness to train and reskill later in life with the same sort of intensity that you might have had at the start of your life.”

(You can read HRM’s interview with Daniel Susskind here).

Tips to become future-ready

Directly following Susskind’s thought-provoking speech, we had the privilege of diving into the fascinating brain of Dr Ben Hamer CPHR, AHRI board member and PwC Future of Work Lead.

Hamer was able to put a lot of Susskind’s insights into action. For example, lifelong learning was a key theme in his presentation, too.

“We need to be spending a minimum of 15 per cent of our working week on upskilling and reskilling in order to remain current,” he suggested.

This could be employer facilitated in some instances, but Hamer said employees need to maintain their own curiosity. This could be as simple as listening to a podcast every day, he said, or signing up to a Coursera course.

“Think about the micro-credentials and micro-learning that you can embed into your workday.”

“For every dollar that an organisation spends on wellbeing, there’s a $2.40 return on the bottom line.” – Dr Ben Hamer

Hamer had a huge amount of value to add to the FoW conversation, and we will bring you more snippets in the coming weeks, but for today, here’s a top line look at his thoughts:

- A potential innovation boom – Talk of the ‘death of the CBD’ has proliferated since many major cities have told employees to work from home, but Hamer said the suggestion that the CBD will cease to exist as a result of this is inaccurate. It will just change. Maybe for the better.

“The CBD has historically been extremely resilient, and will continue to be so. We are seeing that tenancy and the price of renting in the CBD is going down, which means that those organisations located on the CBD fringe, like start ups and tech companies, that were previously priced out of the [inner city], are now able to come in.

“So we’re going to have more diverse organisations occupying the CBDs which has the potential to create an innovation spike,” said Hamer.

- Invest in middle management – Leaders in the middle section of an organisation have received a lot of airtime at this convention – Amy Edmondson mentioned that they’re critical in ensuring psychological safety within a team – which is interesting when we consider that some people have previously argued that this is the obvious business area to trim fat, claiming middle managers to be an obsolete function.

Hamer sees them as mission critical in helping to upskill and empower employees, which is the most impactful way for leaders to strengthen and grow their company moving forward.

“We did some modelling with the World Economics Forum and found, if we could close the skills gap in Australia, we would see an uplift by 5.9 per cent to GDP, and the creation of 200,000 extra jobs. Now is not the time to take the foot off the pedal as far as skills are concerned.”

- Invest in wellbeing to boost the bottom line – The pandemic and subsequent lockdowns mean “increased incidences of isolation and loneliness“, said Hamer, adding that increased working hours are contributing to alarming rates of burnout (he said 61 per cent of employees reported an increased workload since working remotely). Making wellbeing a key investment area, now and into the future, will determine which businesses are likely to thrive.

“For every dollar that an organisation spends on wellbeing, there’s a $2.40 return on the bottom line. So it’s a ‘no brainer’, no regrets investment in wellbeing, from a social but also a commercial perspective.”

- Our digital skills are lagging – “For digital skills, [Australia] ranks 23rd in the world – countries like Mexico are above us. For a first world nation like ours, we should be much higher than that.”

Under investment in technology at a government level is part of this problem, he adds.

“Over the next five or so years, [Australia] will be secondary recipients of whatever countries like Germany, China or the US invests in as far as technology goes.”

Considering not much is happening on a national level, this means employers have a great opportunity to take the lead and trial innovative technology to set themselves up as employers of choice.

- Offer horizontal growth opportunities – Gen Z workers are expected to have 17 different jobs over five separate careers, Hamer said. So HR professionals need to think differently about how to retain young talent.

Employers have need to re-think the initiatives to bolster employee loyalty or to reduce turnover for millennials and Gen Z employees, he said.

“How do we think about and acknowledge that they’re only going to stay in the role for a couple of years, and plan a career path [for them] so we can give them more and more opportunities. It’s not necessarily always about needing to climb the corporate ladder. It’s also about those horizontal opportunities where they can develop skills.”

Mapping out your journey

There have been quite a few FoW insights to digest so far. You’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed at where to start when planning your own strategy.

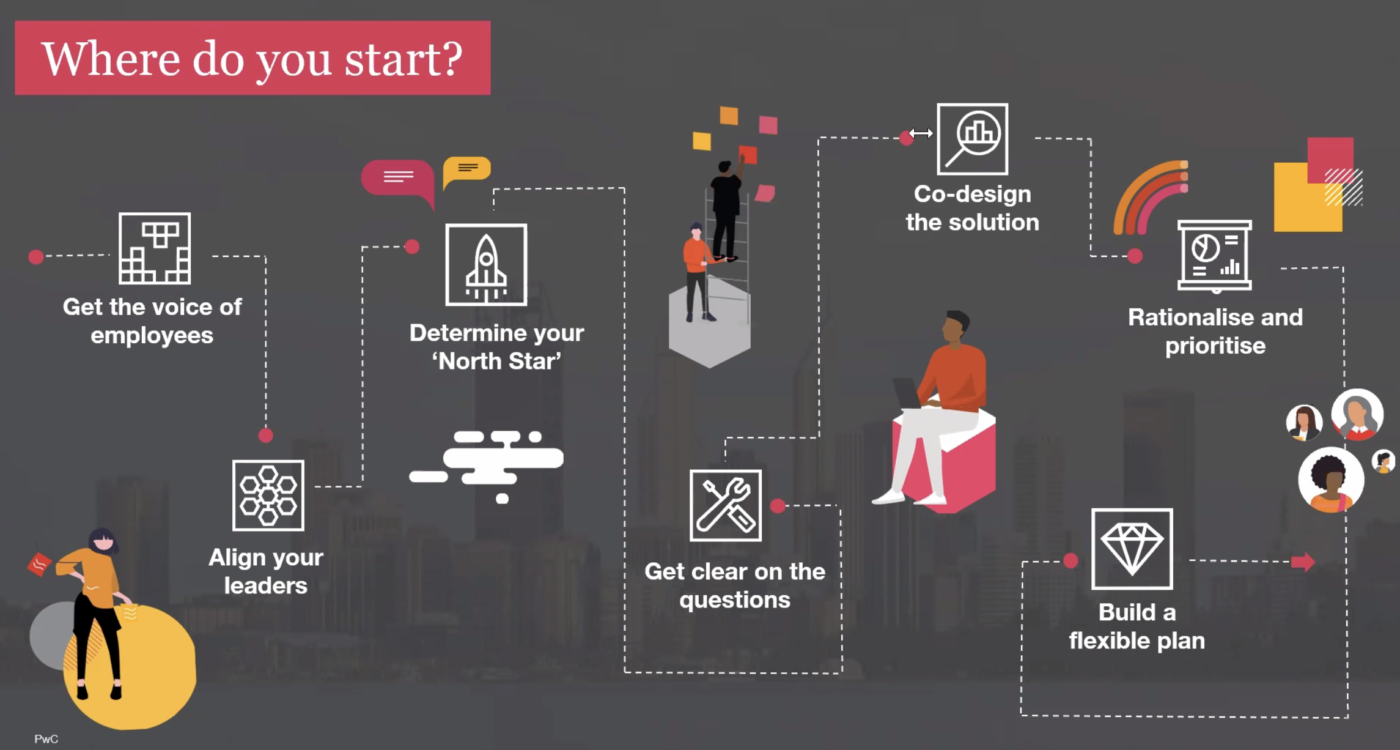

Luckily, Caitlin Guilfoyle, Future of Work, PwC Australia, offered an easy-to-digest road map for you, as shown in the image below.

Guilfoyle’s seven-step process includes:

- Get the voice of employees – Before you start planning, you need to know where your employees stand. “This is more than a survey or a pulse check. This is understanding, on a deep level, the motivation of your workforce,” said Guilfoyle.

- Align your leaders – “One of the challenges we see at the moment is a disconnect between senior leaders and employees.”

By taking the employee voice data to leaders, you can demonstrate any misalignments and get everyone on the same page for any future planning. - Determine your North Star – Where is your organisation heading and does every step you take align with that direction? Ask yourself: “What is the vision of your organisation into the future? Not just the mission statement you put out to your customers, but really, who do you want to be?”

- Get clear on what you need to learn – Ask questions with the aim of identifying factors such as the skills your organisation already has and the ones you’re missing. Guilfoyle pointed to a recent PwC resource which includes a list to help get you started.

- Co-design the solution – If you want employees to buy into the process, you’ve got to include them in the creation. That will look different in every company, but what matters is that employees feel their perspective has been considered. “We know when people are involved in designing a solution, they are more engaged with it. The solutions are richer when there are more voices developing it.”

- Rationalise and prioritise – Determine what programs and initiatives are working and align those with your North Star. Lose the rest to avoid distracting people from your end goal, or falling victim to attention residue.

- Build a flexible plan – “Two weeks ago in Melbourne, we might have thought that we were on track to return to the office. This reminds us that flexibility has to be built into your plan.” After all, the motto for 2020 and 2021 may as well be: ‘You never know what’s around the corner’.

Keep an eye out over the next few weeks for an article unpacking Aaron McEwan’s thoughts on revolutionising the employee value proposition, as well as more from Ben Hamer on his important myths to bust about the future workforce.

Want to catch up on the key insights from days one and two of the convention? You can read them here and here, respectively.