The Government is adopting at least one of the Franchising Inquiry’s recommendations. This could be the end of franchising as we know it.

Chatime may be popular with its customers, but it’s about to become even more unpopular with its staff. The global company which is making the most of the latest Bubble Tea beverage craze, is the newest case in a string of underpayment scandals, joining big names like 7 Eleven, Pizza Hut, Caltex, Domino’s and Retail Food Group (Donut King, Gloria Jeans, Brumby’s etc).

But if recommendations from a recent parliamentary report into Fairness in Franchising (the 17th inquiry into the industry in the last 30 years) are taken onboard, the beverage giant could receive more than just a slap on the wrist, with civil penalties listed as one of the many suggestions made in a bid to completely restructure the failing franchise model.

So, what’s the tea?

Chatime is thought to be the largest teahouse franchise in the world, with hundreds of outlets across 38 countries. The beverage phenomenon of ‘Bubble Tea’ (a cold, sweet tea with tapioca balls) originates from Taiwan, as does the Chatime’s major shareholder La Kaffa, which owns 55 per cent of the Australian franchisor.

The other 45 per cent is owned by Iris Qian and Charlley Zhao directors of Australian franchisor Infinite Plus, who set up Chatime in Australia in 2009. The FWO confirmed the two were also guilty of underpaying staff in a separate business – bakery chain Dough Collective – which has since gone into liquidation. The chain was paying staff as little as $12 per hour (total underpayment costs are estimated to be $350,000 across four Sydney stores).

This week’s investigation from The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age uncovered that they’ve been doing the same thing with their existing business, Chatime. It’s possible employees of Chatime have been knowingly underpaid by millions, dating as far back as 2009.

A 2018 audit by the FWO, covering a five month period from August to December in 2016, found 150 workers who’d been underpaid (amounting to $113,494 in NSW and $62,975 in Victoria) and ordered Chatime to repay these costs by 18 September 2018.

The SMH article said if the audit had dated back to 2009, it would show employees in the corporate offices had been underpaid up to $6 million, and if they included the franchise network “that figure would conservatively blow out to well over $10 million”.

According to the article, “most of the underpaid workers are foreign students on visas from China and Taiwan too afraid to complain to authorities for fear of deportation. Many breached working restrictions attached to their visas to survive.”

It goes on to say that the 2017 Domino’s underpayment scandal caused a conversation behind closed doors with the Chatime board (fearing their heads would be next). According to the SMH, the board floated the idea of moving their employees onto the fast food award in an attempt to clear their name of underpayment claims, but didn’t end up taking any action.

The FWO has said the investigation into Chatime is ongoing, and employees are still waiting for back payments. In a statement to the SMH, the company said: “We do not propose to comment or otherwise correct any of the assumptions you have made (some of which are erroneous), as it would be inappropriate to comment on matters that may be under investigation by a regulator, potentially compromising not only confidentiality but the integrity of an investigation.”

But patience is wearing thin, and this new case of underpayment within a franchise business might spur bipartisan adoption of the recommendations from a damning 369 page parliamentary report released in March.

Putting their foot down and improving regulation

Franchising is a $170 billion industry that in 2016 was estimated to have contributed to 9 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). Likening itself to the Royal Banking Commission, the Franchising Inquiry highlights all the ways in which franchisors have taken advantage of poor corporate governance standards, and calls for ASIC to “take a much more proactive role in monitoring franchisor corporate governance and taking enforcement action where necessary.”

The report says: “the current regulatory environment has manifestly failed to deter systemic poor conduct and exploitative behaviour” and, because franchising is governed by its own code and legislation, it “has entrenched the power imbalance” between franchisees and franchisors.

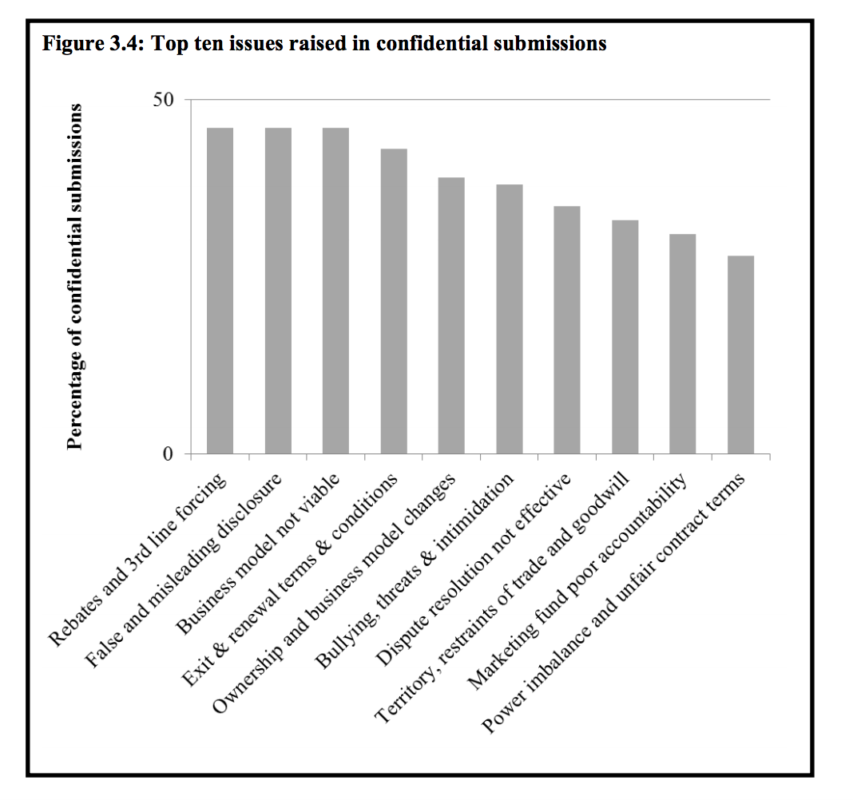

The committee received over 400 submissions, the majority of which were made confidentially. Despite parliamentary privilege, the report said many franchisees feared retaliation from franchisors when making their submissions, which is a major issue at the heart of this report. The franchising model has long been a controversial one. The pressure placed on franchisees to meet daunting head office requirements can be quite considerable, especially for inexperienced business owners. This pressure is frequently passed on to the employees (often migrant workers) in the form of underpayments and poor working conditions.

Referring back to the Chatime example, the SMH says the average franchise costs owners $300,000 for a five year contract.

“The business model is based on franchisees growing sales, not profit, with head office taking a 6 per cent royalty from every sale as Australians slurp on a growing variety of bubble tea. Outgoings include rent, wages, royalties, 3.5 per cent to a marketing fund, payroll system fees, music and mystery shopper costs, cups, syrup, tea leaves, pearls and toppings sourced from the franchisor and refurbishment costs of up to $150,000.”

A lack of transparency was one of the main issues franchisees were having, with many reporting false and misleading disclosures, or entering into a business that isn’t viable as two of the top ten submissions (see chart below).

One of the first recommendations the report made was to set up a Franchising Taskforce to examine the feasibility and implementation of the report’s recommendations. It said the taskforce should consist of representatives from the Dept of the Treasury, the Dept of Jobs and Small Business and, where appropriate, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC).

The SMH today revealed that the government has done just that with a source saying it’s due to meet for the first time later this week.

The taskforce is set to report back to Small Business Minister Michaelia Cash and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg later in the year at which point in time the government will provide its official response to the report.

The Labor party had already previously pledged to act quickly on the recommendations made by the committee if it comes out on top on 18 May.

The report makes 71 recommendations in total, some of the highlights include:

- Changes to the Franchising and Oil codes, such as civil penalties and infringement notices for all breaches to the codes;

- More responsibilities for the ACCC and, in certain circumstances, greater enforcement powers;

- Implementation of the whistleblower protections regime that was first put forward in a 2017 submission;

- Make unfair contract terms illegal (such as unilateral changes to the business model);

- Increase penalty amounts to a level similar to the penalties currently available under the Australian Consumer Law;

- Multiple amendments to the Franchising Code of Conduct (see report for details, recommendations start on page 23);

- Greater transparency and more information provided to potential franchisees upfront and prior to sale (BAS, profit and loss statement, balance sheets etc.)

The report also recommended that a public register of franchise systems be set up, with franchisors asked to provide updated disclosure documents and template franchise agreements annually in compliance with the Franchising Code. This would be made publicly available.

While the ACCC held concerns that it might appear as if its endorsing those organisations if a register was to be created, the committee behind the report said this could be remedied by adding a disclaimer statement.

The committee insists its findings are substantial and that it has taken a holistic approach to encompass the objectives of both franchisors and franchisees and “therefore recommends that the government avoid cherry picking, and instead implement all the recommendations in this report as soon as possible.”

Ensure you understand the legal landscape of your business with AHRI’s short course, ‘ Managing legal issues across the employment cycle’.

I’ve been researching the franchising sector for 30 years and can say, while the sector has always had its challenges, it is far from a failing model. It has been shaken up by investigative stories by journalist, Adele Ferguson, who uncovered serious systemic problems in a particular franchisor, the Retail Food Group, and wage underpayment by franchisees in some large networks like 7-Eleven. There are 1200 franchise networks & 60,000 franchisees with most in reasonable shape.