Do your employees use their allocated annual leave to catch up on work? Are they too scared to admit when they’re sick? You might think the answer is no, but the data around leaveism is startling.

It’s clear we have a problem when an entire phenomenon is developed around a common workplace practice born out of our tendency to overwork. First, it was presenteeism – the idea that employees purposefully work overtime in a bid to impress their boss, often when they’re feeling unwell or exhausted.

This worrying practice has given rise to an even more troubling trend: leaveism. Coined by Ian Hesketh, Project Support, National Health and Wellbeing Forum, and Cary Cooper, Professor of Organisational Psychology and Health, of the Alliance Manchester Business School, leaveism is about employees misusing their leave.

For instance, they might use accrued annual leave to go off sick, rather than admitting to needing their sick leave, or taking annual leave to catch up on work, or working on the weekends.

“Leaveism is when people are worried that their boss will think they’re not coping, so they act like they are,” says Cooper, who is also the President of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) in the UK.

“They might be on a ‘holiday’, but they stay in the hotel room the whole time working when they should be out with their family.”

Always on, always visible

Before putting leaveism on the map, Cooper coined presenteeism in the 1980s.

“During the recession in the 80s, a major newspaper got in touch with me and said that absent rates [at work] were dropping. And they asked, ‘How can they be dropping when there’s so much stress around right now?’ And I said, ‘Would you want to be ill with anything at a time when you’re vulnerable to job losses?’ During times of economic crisis, people are going to [engage in] more face time.”

Leaveism came onto the scene during another economic disaster, the global financial crisis.

“We were looking at police officers in the Lancashire police and asking, ‘Do you turn up to work ill? What’s your workload like?’ We used psychometrics to look at the stress levels of police at that point in time. We found they were taking annual leave to catch up on paperwork.”

This is when it first twigged that leaveism might be a widespread phenomenon. So they tested their hypothesis with other police stations. Yep, it was happening there as well. They broadened their research out to the entire public sector and then the private sector, too.

“We found that it was universal,” says Cooper. “People were easily overloaded during times of financial crisis. [From 2008 to 2015] there were fewer people doing more work, so they were taking time off to catch up, or working on the weekends.”

“Leaveism is when people are worried that their boss will think they’re not coping, so they act like they are.” – Cary Cooper, Professor of Organisational Psychology and Health, and CIPD President.

There’s other data to back up Cooper’s research. In an article for The Conversation, he and Hesketh point to a 2015 Austrian study which shows that employees were using annual instead of sick leave because they were scared their workload would be downgraded if their employer knew they were struggling, or that they’d lose their job altogether.

The overworking habits might make sense to you – we’ve only got so many hours in the day and our workloads are expanding at untenable rates. But why are people lying about needing to go on sick leave?

It’s the negative stigma, says Cooper. “If you have [ten] sick days per year, and you use them all, and you do that for a couple of years running, you might be worried that your employer doesn’t think you’re very robust.”

All of this means burnout rates skyrocket. Of course, remote work makes it even worse as employees not only work longer to make a dent in their to-do list, but also increase their performative styles of working – such as sending emails late at night or logging onto your internal messaging platform on the weekends – to be visible to virtual leaders and prove they’re committed.

How common is leaveism?

Cooper and Hesketh have been researching leaveism for quite a few years now, and Cooper says it’s becoming more common.

In January 2020, Deloitte UK released a report showing leaveism rates were climbing over the previous 12 month period due to our tech-enabled, always-on work cultures.

Fifty one per cent of people had worked outside of their contracted hours to get their work done, 36 per cent said they used allocated time off, such as holiday leave, when they were unwell and 27 per cent did so just to catch up on their workload.

Deloitte also found that 70 per cent of respondents who had observed presenteeism in their workplace also noted that leaveism was present.

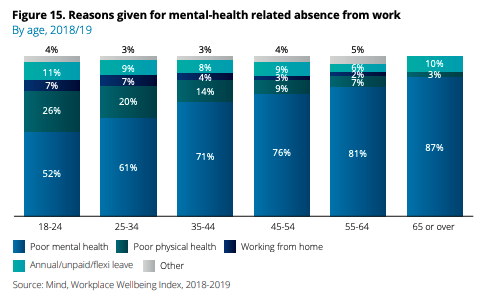

There were also clear patterns in the data to suggest that those with poor mental health might be more likely to fall within the leaveism trap – younger employees in particular – suggesting that some people struggle to disclose their mental health challenges at work (see graph below).

Young employees might also be susceptible to leaveism because they’re usually “the last one in and the first one out”, says Cooper.

“Also, they want to be seen as ‘with it’ and resilient… they’re at the bottom of the greasy pole and they want to climb up it to show they’re highly committed and able to cope with whatever you throw at them.”

Australia’s overworking backdrop

While these numbers are worrying, they aren’t surprising.

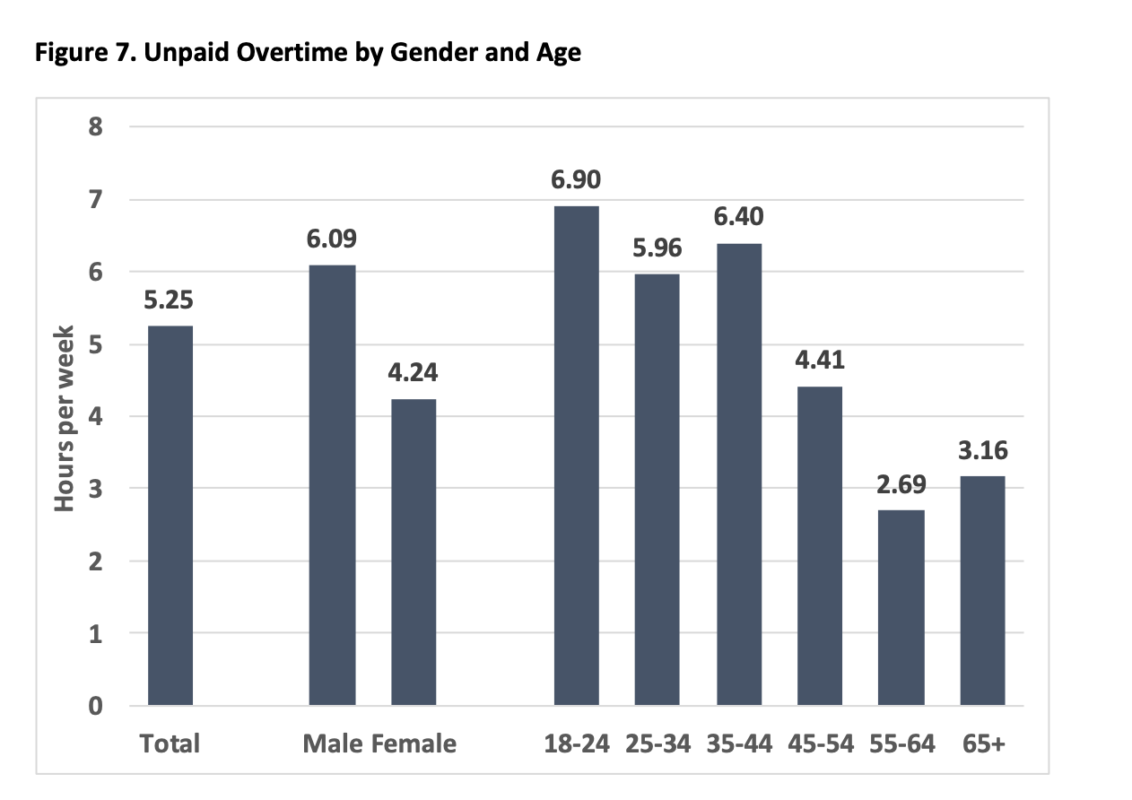

We know from research from the Centre of Future Work that, on average, Australian employees worked 2.9 billion hours of unpaid overtime last year.

New research from University of South Australia shows that over half of employees admit to sending work emails during the evening and 30 per cent on the weekends (and expected a response that day). Of grave concern, 20 per cent said their manager expected them to respond to out-of-hours emails.

In the UK, Cooper predicts leaveism rates could be about to rise in September as the government withdraws the furlough scheme, which covers 80 per cent of employees’ wages. This means millions of workers will return to work and could potentially be on the chopping block as employers try to keep labour costs down, says Cooper.

We could assume that many Australian employees engaged in leaveism behaviours towards the end of JobKeeper for the same reason.

How to reduce leaveism rates

First and foremost, Cooper says all employers should be doing comprehensive wellbeing audits, using proper psychometric methods, and including presenteeism and leaveism sections to identify if it’s a problem.

“This should be done independently and then given to HR. That way you don’t have [details of] individuals or their names, you can just see if the levels are high or not. The CIPD looks at leaveism and presenteeism in its annual report,” he says.

After this analysis, he suggests training managers to recognise it.

“The problem we have is that we promote managers from shop floor to top floor based on their technical skills, not their EQ. We don’t have enough managers who recognise when people have an unmanageable workload. They can’t see symptom changes; they don’t contact them when they’re working remotely.

“In the future when we hire or promote line managers, there has to be parity between their social and technical skills.

“We need to have more emotionally literate line managers. Unfortunately in industry they call them ‘soft skills’, but they’re anything but soft. They’re the important skills we need in the future, particularly in hybrid working.”

Deloitte’s report also suggests:

- Train employees on how to best cover for a colleague who is on leave.

- Consistently remind employees about taking their leave to recuperate.

- Create policies around how employees can redistribute their work should their workload become too overwhelming (this is a great way to normalise asking for help).

- Encourage the use of ‘out-of-office’ messages.

- Proactively hire more people as workloads increase.

- Train managers to spot the signs of leaveism (working late, sending emails while on holiday).

- Help managers to set reasonable expectations for their employees that factor in each person’s individual work style.

If you take away just one thing from this article, let it be Cooper’s parting words: “Expecting fewer employees to do more is a false economy”. It will catch up with you (and them) eventually. Don’t kick the can down the road when it comes to addressing leaveism. You need to stamp it out now.

Learn how to support your people through their mental health challenges with this short course from AHRI. Sign up for the next session on 20 September 2021.