New research on the wellbeing of employees from The Wellbeing Lab and AHRI finds that dealing with people at work is now the biggest source of struggle.

Just prior to Australia re-entering another round of lockdowns, new research from The Wellbeing Lab and AHRI found that employees were demonstrating high levels of resilience.

In May this year, just over 53 per cent of employees said they were living well despite struggles – an increase from 42.1 per cent of employees who placed themselves in this category last August, when this report was last released.

The research also indicates a corresponding decrease in the number of people who say they’re not feeling bad, but just getting by – a term we’ve come to know as ‘languishing’.

One of the researchers behind this report, Dr Michelle McQuaid, founder of The Wellbeing Lab, posits that we’re seeing a big shift in a short period because more people are willing to admit that they’re stressed, worried or anxious, and don’t equate struggle with weakness.

McQuaid suggests acknowledging struggle is actually a hallmark of resilience, whereas those who say they are consistently thriving are expressing minimal struggle, which may not always be reflective of reality.

“What seems to have happened between August [2020] and May [2021] for Australian workers is a recognition that there’s no shame in struggling, and struggling is part of the way we learn and grow, and that it’s possible to thrive, even in the midst of struggle, when we have the knowledge, tools and support to be able to care for ourselves.”

Although the increase in resilience suggests employee wellbeing is moving in the right direction, McQuaid warns these gains could easily be lost if workplaces don’t address some concerning findings from the research, namely:

- Employees are exhausted and lacking in motivation to improve their wellbeing.

- There has been an increase in distrust of management.

- Dealing with people is now the biggest struggle for people at work.

So why are higher levels of distrust lurking in our workplaces, and what organisations can do to improve employees’ wellbeing at work?

Managing people-related stress

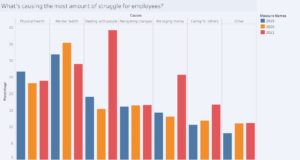

The report found that dealing with people is now the biggest cause of struggle at work for 39 per cent of respondents – an increase from 15 per cent in 2020.

This source of struggle has overtaken mental health challenges, which was the biggest cause of stress for 35 per cent of people in 2020, but now sits closer to 29 per cent.

McQuaid puts the uptick in people-related stress down to three factors:

- Return to the workplace: “Because many workers have been working remotely for an extended period of time, and due to various lockdowns and physical distancing strategies, our social skills [are] understandably a bit rusty.” In short: people could just be getting on our nerves a little more.

- Adjustment in uncertainty: “For many workers, they are trying to navigate this new dynamic of the hybrid workplace and everyone’s a little unsure of what that will be composed of and how it’s going to work practically… The uncertainty can make us more tentative in our relationships.”

- Fatigue: “Dealing with people is always hard and people are feeling worn out as a result.”

To reduce people-related stress, McQuaid says the best strategy is to “understand that feelings of stress are simply our body’s way of letting us know that something important to us is on the line and needs our attention, as evidenced in research by Dr Alia Crumb and Kelly McGonigal”.

These two Stanford University researchers published a book, titled The Upside of Stress, in which they argue people need to embrace stress, not rail against it.

“This means rather than ignoring those signs of stress and trying to distract ourselves or numb them, the best way is to pay attention that uncomfortable feeling, and figure out what is causing it, what help we might need to put in place for ourselves (i.e., self-care strategies) or ask for help from others, then monitor what impact those actions are having and continue adjusting as needed.”

If stress is chronic and impacting wellbeing, she says engaging with EAP services or other external support is a necessary step to take.

Employees are exhausted

Across all four groups measured in the research (employees who identified as really struggling; not feeling bad, just getting by; living well despite struggles; and consistently thriving) wellbeing motivation is “significantly lower than what we’ve seen at any other time, even during the August and March periods last year”, says McQuaid.

“Employees are resilient, but they’re tired. We see that in the PERMAH (positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, accomplishment and health) data for every group except the consistently thriving employees. That’s reflective of exhaustion.”

McQuaid has observed, however, that employers are responding in ways that are inconsistent with the problem areas identified by the research.

“A lot of clients are coming to us and saying, ‘I need to make my workers more resilient.’ And what the data is helping us to say is: ‘Actually, your workers are pretty resilient. We’re seeing lots of resilience, but if you think about a time in your life where you had to dig deep to be more resilient and get through a big challenge, and then when you feel like you’re coming out the other side of it, there’s a great deal of exhaustion.’”

Employers therefore need to provide space for rest and recovery, says McQuaid, and they’ll pay a heavy price if employees aren’t granted the recuperation time they need.

“We risk ending up with a very high proportion of workers being burnt out. And this gain that they’ve made in getting more resilient workers is going to disappear.”

“Workers are really exhausted, so my advice is to not ask them to show up and be their best selves as they move back to work or embrace hybrid working. Don’t tell them that they need to be more resilient right now to get through this next challenge. What workers need is space for rest and recovery.”

Being mindful not to push employees beyond their limits is pertinent in the current climate of unpredictability and uncertainty caused by the recent snap lockdowns.

“There’s a sense of learned helplessness that people can’t plan for anything,” says McQuaid.

“We need to slow down and pause and start to think a little more about what our people need, rather than just what the organisation wants its people to do.”

Distrust of management

There’s been a slight decline in trust of management – from 6.4 per cent of people in August 2020 who said they trust management to make sensible decisions about their future, to 5.3 per cent in May 2021.

McQuaid attributes this spike in distrust to a mismatch between employees’ current psychological state, and their leaders’ expectations.

Employees are exhausted from dealing with the stressors brought on by COVID-19, yet management is demanding more from their workforce, leading to a perception among employees that management is misattuned to their current needs, she says.

She adds that “some of this is fear that decisions are being made behind closed doors”, with employees feeling concerned that management doesn’t have their best interests at heart.

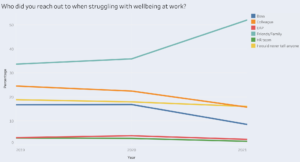

Distrust in management is further highlighted by the finding that only 8.6 per cent of Australian employees would turn to their boss when they’re struggling to care for their wellbeing at work – down from 16.9 per cent in 2020.

This finding could also have increased because of hybrid working.

“Many of us have been in our workplaces less, so perhaps that natural coming across the paths of HR has become harder.”

Distrust in management causes problems to brew.

“At a time when we need managers to help navigate the return to work, to not be trusting them to make sensible decisions about our future really speaks to the fact that there are conversations that need to be had between workers and leaders to figure out what this next stage of work is going to look like.”

Given the current skills shortage, and Microsoft’s recent study which found that 40 per cent of employees are contemplating leaving their jobs, most workplaces can’t afford to risk having people leave.

There’s also no one-size fits all approach, and McQuaid emphasises that providing support should always involve engaging employees in an open dialogue.

“Don’t mandate one organisational answer without talking to your people and asking them what they need. Employers are here to help their workers navigate [this situation], and that will be part of restoring trust because when workers feel they don’t have a voice, that is where employees start to mistrust.”

Employers mandating a return to work, for example, may stem from an often ill-founded concern that employees are more inclined to remain at home.

“We are naturally wired to come back into the workplace because we want to belong and be connected to other people… As much as we enjoy having greater flexibility at home, when teams regularly start coming back together in any form, chances are that more of us will drift to that than pull away from it,” says McQuaid.

Do you want to improve your employees’ mental wellbeing? Book in for this session at AHRI’s convention, TRANSFORM 2021, on August 12 that will explore psychological safety with Danielle Jacobs, psychologist and co-founder of The Wellbeing Lab, and Fiona Michel FCPHR, non-executive director, AHRI, and chief people officer, Vector.

Secure your place with certainty with the option to move to a virtual ticket or receive a refund if you’re unable to attend in person due to COVID-19 restrictions.