The insights from AHRI’s annual Diversity and Inclusion conference are just the start of the conversation. What happens next is up to you. Read expert insights on psychological safety at work, refugee treatment and more.

The fact that AHRI’s Diversity and Inclusion conference saw record registration this year says it all: D&I is still firmly planted at the centre of HR’s agenda, despite the pandemic tightening organisation’s purses.

AHRI’s CEO, Sarah McCann-Bartlett, reaffirmed this message in her opening address to a room of around 200 in-person attendees and hundreds of virtual delegates.

“Right now is the time where we can collectively push the D&I agenda forward.”

It’s on those wielding organisational influence to call out the discrimination and elevate minority voices, she says, and leaders need to model that it’s okay not to have all the answers.

“As someone who is neither an HR or D&I practitioner, and doesn’t have lived experience, I can sometimes feel nervous about using the wrong terminology, saying the wrong thing, showing my ignorance or showing my privilege, and I know that I’m not alone.

“It’s okay not to know everything, but it’s not okay to live in ignorant bliss… It’s on us, on people like me, to educate ourselves and not burden the diverse community with the task of getting us up to speed.”

We’re at a point in time when we’re “pushing against an open door”, she says, so the lessons from today’s keynote speakers and panelists need to be taken back to our workplaces and put into action.

HRM has rounded up some of the key insights, as well as some practical takeaways from speakers and panelists:

This is a long article, but we’ve written it so you can skip to the part that most interests you. Here’s what it covers:

- Human Rights activist Craig Foster’s thoughts on Australia’s treatment of refugees, and HR’s role in the big-picture solution.

- A panel of experts offering tips for how to think about psychological safety in your workplace (with a quick case study).

- Sex Discrimination Commissioner Kate Jenkins on how to respond when a victim doesn’t want to reveal who sexually harassed them.

- Quick food for thought to help reframe your thinking on important D&I topics.

The epitome of a true leader

Standing up to protect vulnerable people – that’s Craig Foster’s MO. Listening to the former Socceroos captain and human rights advocate speak, you can’t help but be filled with a sense of passion and an urgent desire to do more to help the refugee community.

HR professionals aren’t his usual target audience, but he’s clearly excited to share his wisdom with so many influential leaders.

“The opportunity to get here… [in front of] a whole group of HR practitioners, whose focus is to create greater belonging for all of our communities in this country through employment and workplace culture, that’s incredible.”

Foster’s passion for his work is contagious. He spends the first 15 minutes on an unplanned tangent about bringing one’s whole self to work, a concept he’s familiar with from his time on the soccer field.

He recalls being told not to be so liberal in sharing his political views. It might upset the board or sponsors, people would tell him. Or, ‘It’s not what the fans want’. But why should players have to leave parts of themselves on the sidelines, he asks? If the fans didn’t like what he stands for, they’re no fans of his.

Also, asking people to separate their political views from their work identity is a futile exercise, he says.

“Everything is political. Your company is certainly highly political. Life is political. As soon as two or more people get together, it’s political. Sport is political, so let’s just get on with the reality of the situation [so we can get to] the authentic nature of some type of discussion about where the boundaries lie.”

Speaking of the experience of working on the #saveHakeem campaign (you can read HRM’s article on that here) and his other refugee work, Foster says his life was never the same after seeing first-hand the treatment of these people.

“I’m here to say, ‘Can you speak up on the refugee issue, please? Because you’re Australian, and we all have an obligation.’” – Craig Foster, Human Rights Activist.

Now he spends a majority of his energy ensuring these people’s stories are told.

He speaks of the refugees currently held in Melbourne’s CBD in hotels. One man in particular has been there for 15 months, following eight years in detention.

“The man said to me, ‘Our brains are dead. I haven’t read a book in 8 years. I used to read 500 pages a week, but now I can’t read a single page’. He said, ‘I would rather sleep 24 hours a day than deal with my brain’. He has spent 2900 days in captivity, and [recently] he said to me, ‘We feel as though we’ve been jailed for life, and that we are dead.'”

Foster wants stories like this to shock you. He wants it to have such an impact that you go back to your organisations and social circles and commit to making a difference.

“Multiculturalism is not just congratulating ourselves that we have a bunch of Kurds and Muslim Australians in the country. No. We have to stand shoulder to shoulder, and that’s what you’re doing in this room within your own companies… The power that’s in this room is extraordinary.”

This will be challenging in the face of COVID-19, he admits, as Australia will see negative net migration this year. So he encourages the room to turn their attention to the wealth of experience already on home soil. We already have a mass of skilled refugees to leverage, he adds, and most are highly trained and full of potential.

“A quick Google search tells you that entrepreneurship of refugees in Australia is higher than the average level, and the contribution to GDP, not to mention broader society, is exceptional.”

But Foster says his main takeaway isn’t just a case for hiring more refugees.

“I’m here to say, ‘Can you speak up on the refugee issue, please? Because you’re Australian, and we all have an obligation.’”

Implementing psychological safety

You would have heard the phrase ‘psychological safety‘ a lot in recent months, but what does it actually mean? Based on research by Amy Edmondson – who will be speaking at AHRI’s National Convention and Exhibition in August – the concept encapsulates the environment in which someone can be comfortable expressing themselves and sharing concerns and mistakes without fear of embarrassment or retribution.

“It’s not about feeling soft and comfy and cosy,” says session facilitator Lynda Edwards, lead consultant APAC at the NeuroLeadership Institute. “It’s about candour. It’s about having those [tough] conversations in a way that actually moves the needle on making your organisation more competitive.”

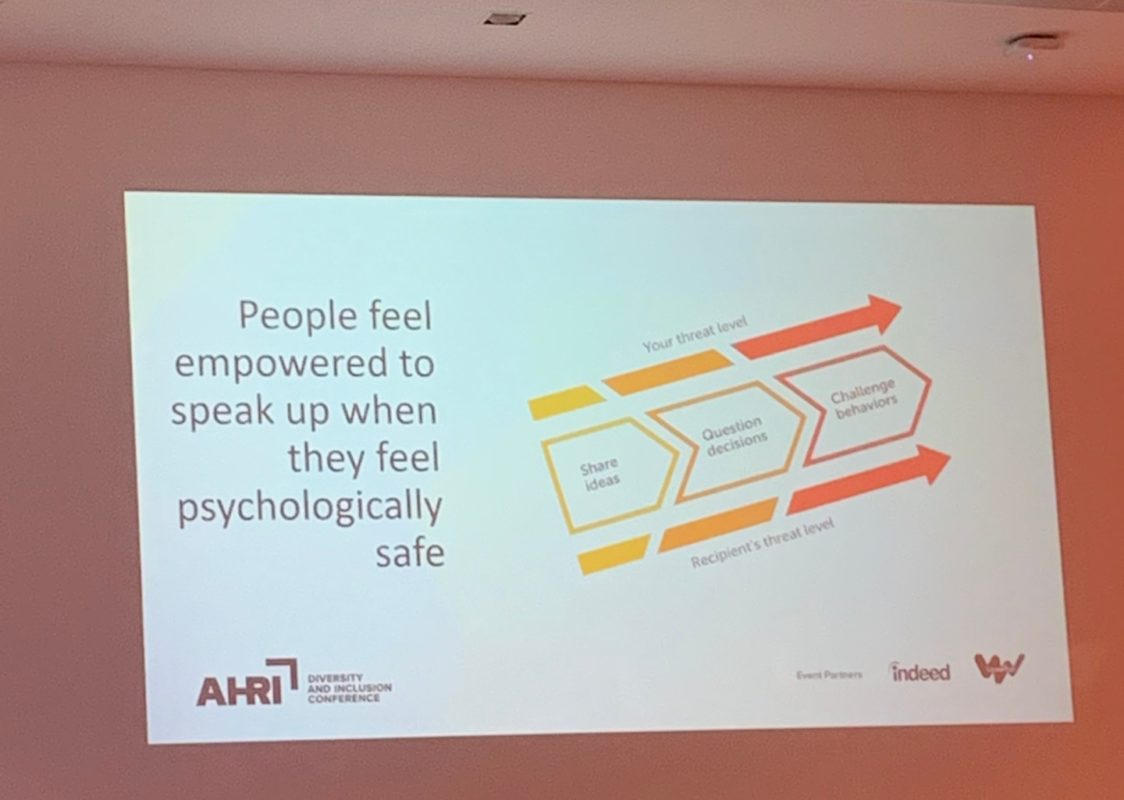

Edwards goes on to outline the various ways in which our brains react to non-psychologically safe environments. In simple terms, the more complex the situation is, the higher threat level we experience (see image below).

“There are no Sabre-tooth tigers anymore, but there sure as heck are some really interesting people we have to engage with – the tough employees or the tough conversations with a really scary boss,” says Edwards.

This triggers our fight or flight response, she adds, and it’s only when we have robust psychological safety frameworks in place that we can respond productively.

Experts including organisational psychologist Amanda Ferguson; Jay Epps, senior manager, workplace health and safety at QBE; and Alex Rowe, assistant state inspector psychological health and safety, and Edwards presented initiatives to help HR professionals assess their organisation’s level of risk and start conversations about psychological safety with executives.

Here were some of their key points:

- To assess your business and identify potential psychological risks, utilise psychosocial risk assessment tools such as People at Work – it’s free!

- Consider job design, says Rowe. That means assessing the responsibilities of a person’s role and ensuring they have the adequate skills and resources. It also means considering who is managing them and if they’re getting what they need from the relationship.

- When talking to your executive team about setting up psychological safety frameworks, do so alongside your risk and workplace health and safety representatives. This will help to bolster your message and maintain executive buy-in.

- If you’re looking to reduce threat levels in your organisation, Edwards suggests using the NeuroLeadership Institute’s SCARF Model – which stands for status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness and fairness to assess differences in employees’ social motivation.

- Consider job crafting to encourage employee autonomy and control, says Ferguson. Individual employees need to be entrepreneurial about their own role, she says.

- Don’t forget your junior workers, says Epps. Many of them haven’t had enough time to develop resilience in the face of professional challenges, so you might need to pay extra attention to them.

- As a leader, don’t assume people will come to you with their issues, says Edwards, because most of the time they won’t. Rowe adds that workers usually spot the signs of a lack of psychological safety well before leaders do. So encourage leaders to take time to connect regularly in a genuine way, so nothing slips through the cracks.

- Hook your business case for psychological safety on whatever the CEO is talking about to get it over the line (i.e. improving engagement, improving the finances, working in agile ways).

“There are no Sabre-tooth tigers anymore, but there sure as heck are some really interesting people we have to engage with – the tough employees or the tough conversations with a really scary boss.” Lynda Edwards, lead consultant APAC at the NeuroLeadership Institute.

A quick case study

In 2019, QBE surveyed its employees and asked if they felt safe to “speak up without fear of negative consequences”. Only 54 per cent said ‘yes’.

To combat this, QBE developed a framework to conduct a comprehensive risk profile of the organisation which acknowledges different types of psychological safety that workplaces need to address. They are:

-

- Innovation safety – do people feel confident to speak up and share new ideas?

- Challenge safety – can people safely and constructively challenge others? Do they feel safe to question the status quo?

- Support safety – do people have a safety net to fall back on when they make a mistake?

- Inclusion safety – does everyone get an opportunity to share their point of view?

The hardest part, says Epps, is the final stage in this process, which is calling people out if their behaviours aren’t aligning with QBE’s four types of psychological safety. To refer to Edward’s graph shown above, challenging certain behaviours is most likely to spike our sense of threat (as well as that of the recipient) and that often leads to highly unproductive behaviours.

With this in mind, Epps says QBE engaged a third party expert to train its people in this critical skill. As Edwards put it, by taking a nuanced, layered approach, you’re helping to “build the cognitive muscle” rather than jumping to the hardest part first – calling people out.

Does your organisation have a great D&I initiative that’s award-worthy? AHRI wants to know about it. Submissions for nominations for the AHRI awards close on 28 May. Click here for details.

Taking a trauma-led approach to sexual harassment

HRM has written fairly extensively on sex discrimination commissioner Kate Jenkins’ thoughts on HR’s role in preventing sexual harassment, (you can read her thoughts on the ‘don’t trust HR narrative’ here, and her advice on preventative measures HR can take here).

Worth quickly touching on, however, was Jenkin’s response to a common question she has been asked for decades: what should you do if someone tells you they’ve been sexually harassed but won’t reveal the harasser?

“I think we’ve [previously] had this idea that you deal with sexual harassment by disciplining and getting rid of the bad egg. We’ve shifted now to say, actually you have other obligations. The welfare of the person raising this issue is actually very important,” says Jenkins. “[Investigate] why that person is unprepared to give you that information?”

When someone comes forward with a sexual harassment complaint but asks you not to do anything about it, they don’t actually mean that, says Jenkins. The subtext of what they’re telling you is that they don’t want to face the negative consequences of speaking out.

“A lot of our [reporting] systems involve paying a personal price,” she says. So first and foremost, you need to create a trauma-informed process for reporting.

“My second point would be to say that when someone comes forward, even if you don’t have the evidence, you should be thinking about what data you do have and what prevention activities you could take. Also, when someone comes forward… it doesn’t mean they won’t want to do something about it later.”

HR has more tools in their bag than just investigating the issue, she says.

You could also set up anonymous reporting lines, which will give you some data about what is happening in your organisation without putting individuals at risk.

“Your voice will never be as loud as the whisper of the most senior person in the room. So to create change, you must reach that person.” Ian Bennett, partner at PwC.

Food for thought: Quick tips to take back to work

There’s so much more we could have talked about from the day. Here are just a few of the other interesting points that were raised throughout the day:

-

- Understand nuance. Burnout isn’t a mental health condition, but it can lead to mental health conditions, says Amanda Ferguson, organisational psychologist.

- Coaching and mentoring. “Mentoring is like having a friendship with a helpful power dynamic,” says Yenn Purkis (read more on Yenn’s story here).

- Provide context. AFL player Alicia Eva said when delivering difficult news to your team, you can’t assume everyone has context behind the decisions being made, and it’s therefore your responsibility to educate them. If, however, the contextual information can’t be disclosed, make that point clear to your team.

- Join forces. Josephine Sukkar, chair of the Australian Sports Commission, urged organisations to only form partnerships with companies whose values align with your organisation.

- Learn what terms you employees like to use. For example, Yenn Purkis says they prefer the term ‘autistic person’ not ‘person with autism’. It’s called identity-first language.

- Identify and challenge stereotypes. One commonly held stereotype that Joanna Maxwell, director of the Age Discrimination Team at the Australian Human Rights Commission, has come across is that older people struggle to think clearly. But Maxwell says, “Until at least the mid 80s, your overall level of thinking capacity does not drop off. In multi-generational teams, you get the benefit of nimble younger workers, and you have older workers with crystallised knowledge.”

- Want to start an employee diversity committee? First find your allies and then ask hard questions like who is missing? Next, set tangible goals, get buy-in from leadership and then advertise the group; let allies know they’re welcome – Erin Waddell, regional Co-Chair of Indeed’s Access Inclusion Resource Group.

- Know where to start. LGBTIQ+ initiatives are a great place to start as you never know who that might impact. You can’t look around a room and see who might be part of the LGBTIQ+ community, says Ian Bennett, partner at PwC.

- Pay your power forward: “Your voice will never be as loud as the whisper of the most senior person in the room. So to create change, you must reach that person,” adds Bennett.

- Understand nuance. Burnout isn’t a mental health condition, but it can lead to mental health conditions, says Amanda Ferguson, organisational psychologist.

Has the D&I conference left you wanting more? Early bird registrations are open for AHRI’s National Conference in August.