This form of workplace disadvantage is nothing new, but the mass migration to remote work has brought it to the fore.

The national conversation about remote work and COVID-19 too often omits a crucial factor – the fact that 2.5 million Australians don’t even have access to the internet.

While this might suggest the rest of the population has easy access to a good-quality internet connection, that’s not painting the full picture. Over four million Australians are limited to mobile-only data. Others struggle with patchy signals due to their location or budget restraints.

But the issue isn’t just access or costs. Being ‘digitally included’ also means having the skills to use various digital platforms. These are three things many of us take for granted. For a country that consistently rates in the top ten on various First World indexes, the fact that so many people are disadvantaged is worrying.

“There’s been a lot more interest in digital inclusion since the lockdown period,” says Dr Chris Wilson, a research fellow with the Centre for Social Impact at Swinburne University of Technology and co-author of the 2019 Australian Digital Inclusion Index (ADII) – Measuring Australia’s Digital Divide.

“Over the years we’ve seen governments, community groups and commercial organisations start to see digital inclusion as a shared value. There are benefits for all if we can get more people engaged in an online world. Those of us involved in digital advocacy see this as the moment to hopefully push through some change.”

How does the Index work?

The ADII, created in partnership with RMIT University, Telstra and Roy Morgan, was first published in 2016. While the most recent report shows national improvement, there’s still a long way to go.

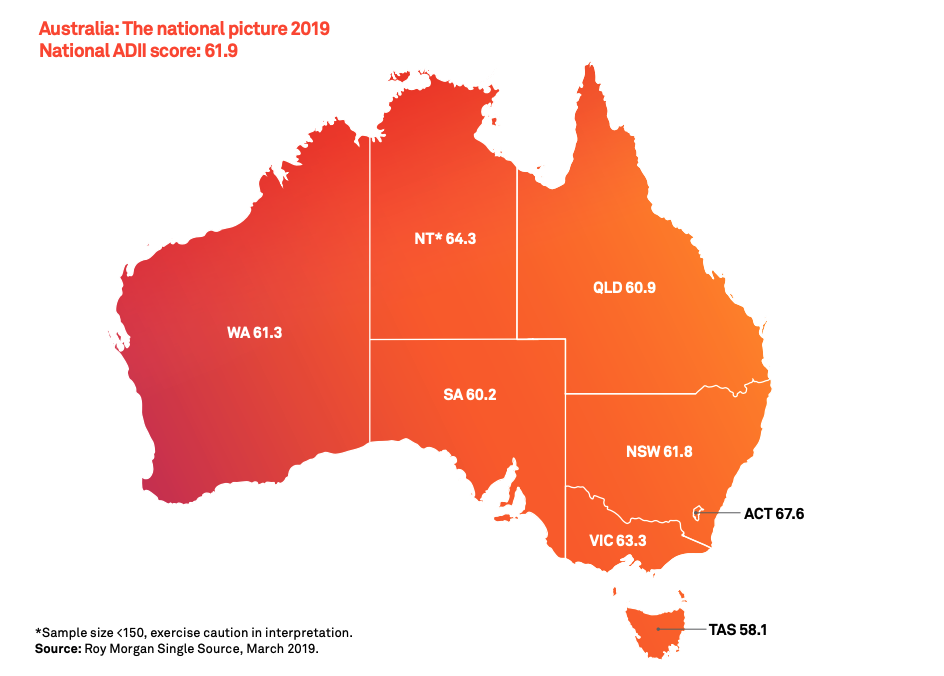

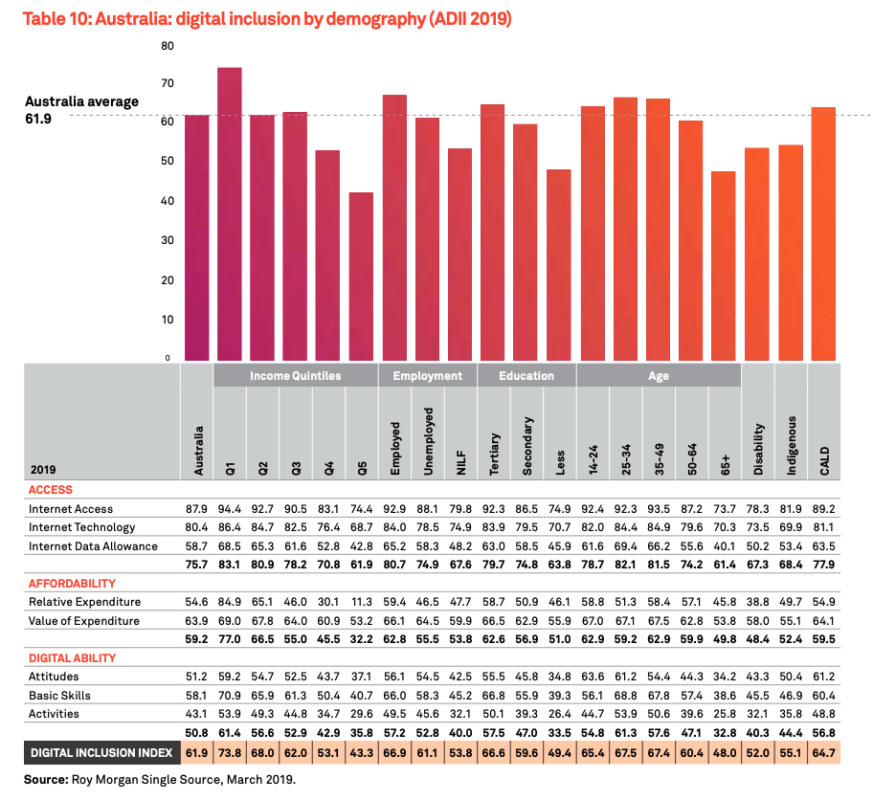

Australian states and groups are measured against three subindices: affordability, accessibility and digital ability. The higher the score, the greater that group’s level of inclusion is. Australia’s overall national digital inclusion index is 61.9. The state with the highest index score is the ACT (67.6 – a 1.3 increase since 2018) and the lowest is Tasmania (58.1 – a 1.2 increase since 2018).

Household income has the greatest impact on an index score. High-income households report a 73.8 index score, whereas households that have an income of $35K or less per year had a score of 43.3. After these low-income households, the groups with the lowest index scores were mobile-only data users (43.7), those aged 65+ (48), those who didn’t complete highschool (49.4) and those living with a disability (52).

Affordability has improved marginally. The ADII shows that people are starting to get more value for money when purchasing digital infrastructure, however it shows we’re spending more money on telecommunications than ever before.

“[Those costs] are continuing to creep up and we know household incomes aren’t creeping up. For middle class or higher income households, perhaps that’s not a big deal. But the pressures on low income houses are extraordinary. They’re often making choices each week, like, ‘do I get my medication or do I get prepaid mobile data so I can receive a call about getting some more casual work?’ It’s diabolical at that level,” says Wilson.

Access has also been getting better over the last five years. The NBN has improved digital uptake in rural Australia, as these regions were prioritised in the rollout. But Wilson warns that this is something of a Bandaid solution.

“We know in regional and rural areas that we’ve got a lot of people on fixed, wireless NBN. But with home-based working increasing, we’re likely to see more pressure on that system during peak times. That’s not going to get any better. It’s really hard to expand the capacity in that technology.

“Most of the big businesses have optical fibre to their premises, but we’ve shifted all the traffic off that network onto the home-based, retail network. It’s coping okay at the moment… but we’re now relying on a network that might be incapable of delivering.”

He says the increasing availability of 5G might offer some reprieve, but it will likely only benefit those living and working in metropolitan areas.

The great divide

Like most forms of discrimination, digital exclusion targets community groups who are already vulnerable.

“Digital inclusion isn’t about an absolute measure, it’s about relativities,” says Wilson. “If the people at the higher end have more skills, everyone assumes that the whole population is at that skill level and we start designing tools, access points and interfaces based on that group. So for those people who were relatively low, even if they’ve had some kind of improvement, the gap widens. They’re effectively going backwards.”

We’re seeing this happen with Indigenous Australians and people living with a disability. Both groups have seen improvements over the last five years, but the index scores of both groups averaged around 20 points behind high-income households and around 8 points behind the national score.

Those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, however, reported high scores, sitting 2.8 points above the national Australian average at 64.7.

Across Australia, women report lower ADII scores than men. Wilson says this could be due to the difference in workplace participation rates.

Wilson is particularly worried about the low digital inclusion rate of those in the 65+ age bracket.

“There’s this argument that suggests that eventually, when the generation that has grown up with technology ages, the older portion of the population will [be digitally savvy] and everything will be fine. But we’re not seeing that.

“What we see is that once you retire and don’t use technology in the same way, or with the same intensity that you would on a day-to-day basis, that you do lose those skills.”

On the other end of the scale, digital natives – those who’ve grown up with the internet – are also at risk of missing out on valuable information.

“We think they’ve grown up with it, so they should know all about it. That’s an assumption that’s had some really negative effects on the sorts of digital training that we provide to young people. We assume they know things, so we don’t teach them.”

Excluded from the workforce

Working from home over the last few months has benefitted some groups and hurt others, says Wilson.

Speaking broadly, you can put people into two different camps, he says. The first is businesses and communities that were forced to undergo a rapid digital transformation due to the pandemic. People in this group will tend to become more digitally included because of the digital skills they’ve had to develop.

“We’ve seen this across the teaching workforce,” says Wilson. “And that’s not just video-conferencing skills, but also those skills that go along with producing creative materials for a school presentation, for example.”

In the second camp are those who weren’t able to work remotely. Employees in certain industries are likely to become more excluded. Wilson uses the example of people working in the airline industry.

“It’s a completely offline skillset. A lot of the cabin crew are older women and I worry that they’ll never return to the workforce after this. They’re not going to have the digital skill sets to get into these new jobs or the new required way of working. We know that once older women in particular are locked out of the employment sector, it’s very, very hard to get back in.”

“The pressures on low income houses are extraordinary. They’re often making choices each week, like, ‘do I get my medication or do I get prepaid mobile data so I can receive a call about getting some more casual work?’ It’s diabolical at that level.”

Moving forward

Wilson doesn’t foresee this problem ever being completely solved.

“It needs to be a continuous investment in skills across the life spectrum,” he says.

“What COVID might have done is help people to transition their thoughts away from the idea that the internet is a luxury service. I think people forget that it’s an essential service. Living without the internet is incredibly difficult. Living with poor quality or unaffordable internet, or without the skills to use it, is also really, really hard.

“People say things like, ‘If you give people the internet, they’ll just watch Netflix’. But that’s how we received cultural cues and information. When you’re at work, if you don’t have Netflix, for example, you’re cut out of a lot of conversations. The notion that the internet is just this functional thing that you use for work and to educate yourself and therefore that we shouldn’t invest in it because people will just use it to watch TikTok videos, or whatever, is out of touch.”

Real change comes from a coordinated approach from governments, telecommunication companies and employers. On the latter point, Wilson encourages organisations to re-think how they’re offering digital skills training in order to multiply its impact.

“That might be by subsidising home internet costs, providing devices for the home and offering training in the workplace that’s not only applicable for immediate impact on the business, but also thinks about how those skills can be adapted to other aspects of their workers’ lives.

“If you’re doing some database training, for example, why not add some extra basic-level training? When people go home and play with that stuff, they discover new settings or tools that can be brought back into their jobs. They come back to the business with new ideas about technology.”

To look at such training through an employee wellbeing lens, there’s an argument to be made that by giving staff the skills and tools to engage in the online world in a fun and casual way – be that through social media, video-conferencing or entertainment platforms – that they’re more likely to be happier and healthier, and therefore more engaged with their work.

“There’s a cyclic element to this. Investment in staff will pay employers back. When people get better skills and better access to the internet, it plays out across their lives. Sure, there’s a personal benefit. But it’s also a benefit to the business and to the wider economy.”

Learn how to establish and manage a virtual team with AHRI’s half-day course. Discounts available for AHRI members.