Depressing research about the trouble work can cause to your marriage, productivity and health.

Working gives us a sense of purpose and and financial stability. But, if you’re not careful it can also ruin your life. Take romantic relationships, for example. A recent Danish study found a link between divorce and the workplace, with the research suggesting that married people who work with many members of the opposite sex are more likely to split.

Men who work in female dominated workplaces were found to be 15 per cent more likely to get divorced than those who work with mostly men. For women who mostly work alongside men, their marriages were 10 per cent more likely to dissolve.

The researchers looked at all heterosexual Danish unions between 1981 and 2002, focusing on the 100,000 couples who divorced in that time period. While the study doesn’t take into account any other factors that lead up to a divorce, it suggests that increasing the viable options of mates doesn’t exactly assist marital bliss. The safest bet? According to the research, the professions least likely to lead to divorce were a librarian or working on a farm. So maybe the company of books and/or vegetables keeps you on the straight and narrow!

Fascinatingly, the level of the subjects’ education had an impact. The research suggests that the association with divorce risk is “about twice the size among highly educated men compared to low educated. For women, the relationship is reversed and highly educated women have barely any increase in divorce risk in more male-biased sectors.”

What happened to my brain?

Is your mind not as sharp as it used to be? It could be due to the number of hours you put in. According to a 2016 study, a 25-hour work week might be optimal for employees over 40. The Australian study, which looked at the data around 6500 workers, found that functionality was at its peak during a three-day work week. Anything more had a negative effect on memory span and cerebral dysfunction, but working too little (less than 25 hours for men and 22 hours for women) also had a negative impact.

Of the findings, Colin McKenzie from Keio University in Japan told the Sydney Morning Herald: “For cognitive functioning, working far too much is worse than not working at all. In the beginning work stimulates the brain cells. The stress associated with work physically and psychologically kicks in at some point and that affects the gains you get from working.”

While the study only takes into account the correlation between hours worked and performance, researchers consider stress and lack of sleep to be responsible for the decrease in cognitive function, with both factors causing a loss of neurons in the brain. Add caring responsibilities into the mix, which the over-40 population tends to have in the form of raising children and/or looking after elderly parents, and you have yourself some tired, stressed-out workers.

As HRM suggested in a recent article, perhaps a six-hour workday is the answer.

Death becomes them

Working excessively long hours is not only detrimental to performance, it’s also terrible for your health. A 2017 BBC Capital article cited several international studies linking long working hours to serious health conditions and eventual early death. One such study likens overtime to smoking by suggesting that working long hours increases the risk of coronary heart disease by 40 per cent (to smoking’s 50 per cent). Working more than 11 hours per day can render you almost 2.5 times more likely to have a serious depressive episode than people who worked seven to eight.

In Japan, overworking to the point of death is known as “karoshi”, and one in five Japanese workers are at risk of it. Recently the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has defined it as “sudden death of any employee who works an average of 65 hours per week or more for more than 4 weeks or on average of 60 hours or more per week for more than 8 weeks”.

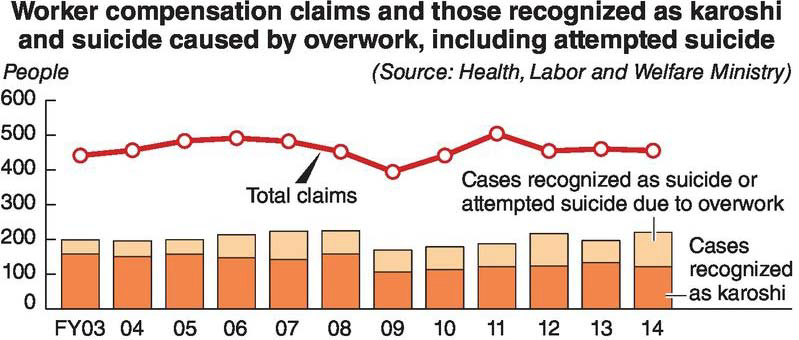

Related to karoshi is karo-jisatsu, or suicide from overwork. There are about 2,000 such suicides in Japan every year. Making the issue more difficult government’s apparent reluctance to record how many overwork-related deaths there are. In 2014 there were over 400 total worker compensation claims of karoshi and karo-jisatsu, but only slightly over 200 were recognised as such.

In one extreme case of karoshi, a 31-year-old journalist worked 159 hours of overtime in one month and died of heart failure. In a case of karo-jisatsu, a 24-year-old advertising worker leapt to her death after clocking 100 hours of overtime in a month.

According to US researcher and author Alex Soojung-Kim Pang we are only good four hour bursts, with the rest of our working days being consumed with “padding” and worry. Some extraordinary achievers were proponents of short work days – think Charles Darwin, Theodore Roosevelt, Ernest Hemingway, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Stephen King and Alice Munro.

Scared yet? I am. Might step away from the computer for a bit.

Access AHRI ASSIST resources for HR guidelines, checklists and policy templates on different HR topics including workplace wellbeing. Exclusive to AHRI members.

Test Test

This is a very interesting read that resonates closely with me, especially the section about Japan’s work culture which exhibits great work-life imbalance. A major strategy that the Japanese government is encouraging to counter this trend is called, ‘Inemuri’, which is simply the need for ‘naps at work.’ I use this in my workplace and it works wonders for managing stress and increasing productivity.

With so much evidence about the effect of excessive working hours on health, there is real irony in how can we continue to allow doctors in training to work regular shifts of 16 plus hours.