Suicide Prevention Australia’s new guide, the first of its kind in Australia, shows employers how to elevate their mental health training to support employees at risk of suicide.

Warning: this article discusses mental illness and suicide and may be distressing for some readers. If you or someone you know needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636.

The national peak body for suicide prevention, Suicide Prevention Australia, has unveiled Australia’s first suicide prevention framework for workplaces.

Suicide Prevention: A competency framework’ aims to help employers uncover the gaps in their knowledge of suicide prevention so they can respond more effectively to employees experiencing suicidal thoughts and behaviours.

HRM spoke with Suicide Prevention Australia’s CEO Nieves Murray about how the framework helps workplaces and what employers need to understand about suicide prevention.

Australian suicide statistics

Before we dive into the framework, let’s look at why something like this is so important.

Organisations have done a lot to improve wellbeing offerings over the years, says Murray, especially in the last 18 months. But suicide prevention is still a neglected topic in our workplaces.

“It wasn’t that long ago that suicide was considered a crime,” says Murray. “And so there’s still a lot of misunderstanding around it. It’s very taboo, so those discussions just don’t happen.”

This trend is particularly worrying considering how prevalent death by suicide is in Australia.

Over 3300 Australians died of suicide in 2019, according to data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. That works out to nine deaths per day. For comparison, 1195 people died on our roads that same year. And over 65,000 Australians attempt suicide each year, according to Lifeline.

The ripple effects of these deaths are far-reaching. With every death by suicide, up to 135 people feel its impact. This includes family members, friends, first responders and colleagues of the person who died.

“More than half of the population knows someone who has died by suicide,” says Murray.

“It wasn’t that long ago that suicide was considered a crime.” – Nieves Murray, CEO, Suicide Prevention Australia.

A four-part suicide prevention framework

The Suicide Prevention Australia framework acts as a starting point for employers and includes the minimum standards for:

- Suicide prevention methods;

- Postvention knowledge (intervention conducted after a suicide for those who’ve been impacted); and

- Skills, attitudes, attributes and values that staff need to have.

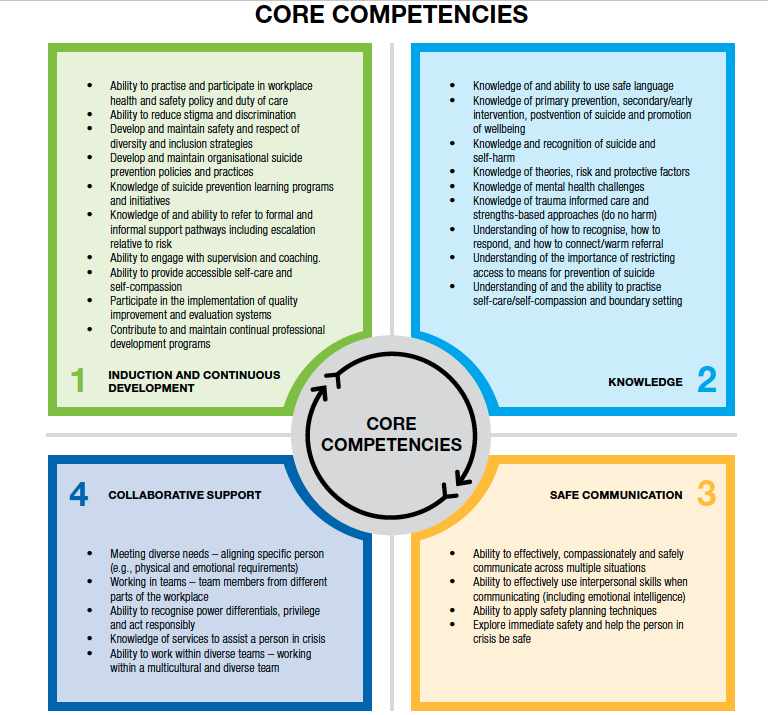

It also outlines the four core competencies that employers need to address (see graph below), including:

- Induction and continuous development – i.e. tailoring policies and processes to ensure any risks to employees’ psychosocial safety are identified, understanding the details about how to support employees and mitigating any risk factors.

- Knowledge about preventative measures – i.e. ensuring employees have the adequate information and expertise to support someone in crisis. It’s at this stage that you might introduce training programs to fill any gaps in your organisation’s knowledge.

- Safe communications – i.e. making sure employees know how to communicate on matters of suicide and suicide ideation in a compassionate, safe manner. This could include learning how to actively listen, validating the person’s experience and being present with them.

- Collaborative support – i.e. engaging in trusting, open relationships with each other. This requires a manager to assess for things such as a power imbalance, the unique needs of the people involved and how/when to escalate an issue.

It also includes details about how to implement its four competencies. Click here to download the framework.

Identifying the gaps in your organisation

The framework was created in consultation with organisations that work in suicide prevention day in day out, says Murray, including well-known names such as Black Dog Institute, Beyond Blue and Lifeline.

It allows employers to conduct a gap analysis on their current mental health offerings to make sure the right people are getting the right training.

Though the framework doesn’t outline how to handle an employee who might be moving towards suicide, it does point employers to resources to gain that important training.

The full list of training options is extensive, but a couple Murray suggests focussing on include:

- Black Dog Institute’s QPR – The Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR) model is a 60-minute self-guided online training course on how to deter someone with suicidal thoughts or in the ideational phase of a suicide plan.

- Livingworks’ Start – A 90-minute online course that teaches participants how to recognise if someone is having thoughts of suicide.

- Livingworks ASIST – A two-day interactive course that teaches participants to intervene when someone is at immediate risk of suicide.

AHRI’s Mental Health At Work short course is a 90-minute session that aims to give HR professionals the tools to tackle mental health challenges in the workplace.

If an employer is already worried about an employee, Murray’s advice is straightforward: ask them if they’re thinking about suicide.

“There’s an incorrect assumption that if we talk about suicide it might put the idea in someone’s head, but that’s not true,” she says.

“If you’re worried about someone, ask the question, listen to their story without reacting and ensure they seek support from their doctor, a crisis support service like Lifeline, or their preferred medical professional.”

Asking an employee if they’re suicidal isn’t easy, but it can be a life-saving question. Importantly, you need to be prepared if the answer is ‘yes’. That’s why Murray says all organisations should be seeking mental health first aid, or undertaking training programs like those listed above.

It should be treated like any workplace health and safety issue, says Murray.

“If someone has an accident at work, most people have first aid [training] so they can help even if a medical professional isn’t present.

“The more people that have basic training to identify when an employee might be moving towards suicidal risks, the more lives we’ll save.”

“The more people that have basic training to identify when an employee might be moving towards suicidal risks, the more lives we’ll save.”– Nieves Murray, CEO, Suicide Prevention Australia.

The remote workforce

Spotting the risks in the remote workforce is harder, says Murray, but it’s not impossible.

Some warning signs to look out for are:

- Change in behaviour

- Starting work late

- Not working at all

- Working long hours

- Submitting subpar work, or work that’s not to their usual standard or

- Missing deadlines or constantly being late.

“Keep an eye on their deliverables,” says Murray. “Not just for productivity, but because it can signal something is wrong.”

Thankfully the past year has increased our attention to mental health issues and Murray believes it has also sped up our maturity around discussing suicide.

“If there is a silver lining to the pandemic, it’s that it has heightened our awareness of the need to connect with others. It has heightened our awareness to notice changes in a person’s behaviour.

“It has given us licence to be more more deliberate in asking questions, maintaining our personal connections, and making sure the people we love are safe.”

Want more mental health resources? You can read HRM’s story on spotting the red flags of mental ill-health, learn about self care in the workplace or – if you’re one of the many Australian’s back in lockdown – here are the best tips from astronauts on handling isolation.

If you, or someone you know, needs help, contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636.