As leaders are forced to adapt to rapidly changing work environments, a static approach will no longer cut the mustard. Finding your leadership style, and knowing when to switch it up, is crucial.

What do leaders and improv actors have in common? To be effective, you need to be present, adaptive and open. In improv, pulling out the same jokes would make you a poor scene partner. Good improvisers need to be hyper-aware of what’s going on around them so they can respond quickly and make their scene partners look good.

The same rules apply to leadership. You can’t come to work each day and act the same in every situation and hope your company reaches its goals. In a post-pandemic context, leaders face unprecedented challenges, and a narrow-minded approach to leadership won’t help you solve complex issues.

Here’s how Rebecca Edwards, General Manager of People, Culture and Safety at outdoor apparel company Kathmandu puts it: “Leadership is not a position you hold. It’s an action – to encourage and inspire others to be their best with clarity and direction.”

A flexible leadership style

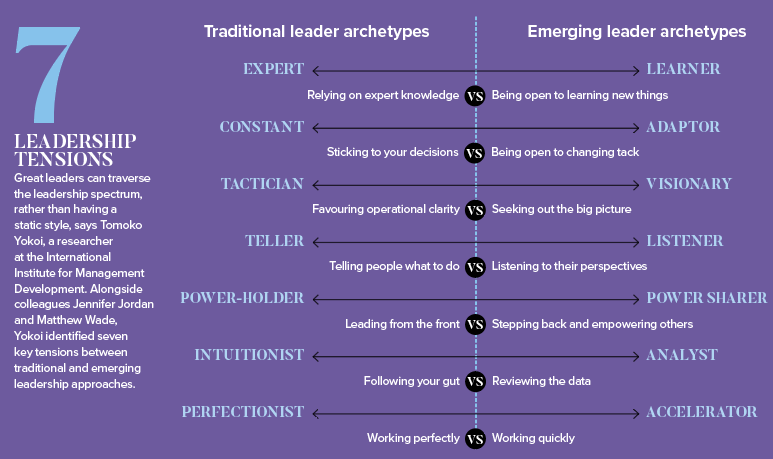

Tomoko Yokoi is a researcher at the International Institute for Management Development (IMD), based in Switzerland. To better understand leadership behaviours, she and her colleagues have spoken to thousands of leaders globally.

“When you think about leadership paradigms, you’ve got these traditional ways of managing and leading. On one end, you’ve got command and control, which are very hierarchical,” says Yokoi. “On the other end of the spectrum, you have tech start-ups which are about agile decision-making.”

They found that effective leaders quickly assess the context, situation and person involved and adjust their approach accordingly. These leaders are consistently navigating the tensions between competing leadership styles. To put these conflicting styles into context, they plotted them out on a continuum (see below).

On one end sat traditional styles (such as the expert or the power holder) and on the other sat their opposite counterparts (including the learner, visionary and power sharer).

Rather than act the same in every situation, adaptable leaders were exercising what the researchers described as a “leadership sweet range” – the ability to enact different leadership styles depending on what the situation calls for, a concept they first unpacked in an article for Harvard Business Review.

“For example, say your organisation is going through a change transformation,” says Yokoi. “An effective leader needs to be able to listen first about what their employees want the vision to be. But to communicate the vision, they would need to then become a visionary leader.”

As both an HR professional and a leader, Edwards understands this dichotomy well. She leads a team of 16 people spanning payroll, learning and development, remuneration and benefits, and talent and culture. She knows her natural leadership tendency leans more toward the listening end of the scale. But during the first COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, she had to become a teller.

“During the last two years there were many times where you had to be more directive than consolidative,” she says. “It’s always important to consider everyone’s thoughts and feelings. But we were facing scenarios that had never occurred before and decisions had to be made fast.

“If you waited too long, the rules could change. The ability to be super-agile, to have the courage and confidence to gather the right information and quickly make a decision, and then communicate – and sometimes over-communicate – to reduce the stress and anxiety we were facing was essential.”

Challenge your assumptions

Widening your leadership range doesn’t mean you have to make split-second decisions for every situation you encounter.

Jennifer Overbeck, Associate Professor of Management at Melbourne Business School, believes that to be adaptive, leaders need to ask constant questions and challenge their own assumptions.

“The biggest change we need to make as leaders is to take the focus off ourselves and put it on our team. We need to make the information flow not just from us to them, but more from them to us.”

So where should you start?

“It’s not about reading the room. It’s the work you do before you even enter the room.”

Start by understanding who you’re working with. Assess their key skills, competencies and commitment. Conducting a survey will help you understand where you stand with your team and how you can lead them.

“The question is, are you going to be courageous and ambitious enough to try and test out something a little bit different?” – Tomoko Yokoi, researcher, IMD

Another technique is to ask lots of questions so you don’t make assumptions based on bias.

She gives an example of going to a doctor because you’re getting headaches.

“The doctor tells you you’re stressed, here’s some medication that’ll take care of your headache,” she says. “[In this scenario] the doctor has asked just enough to have a hypothesis, and then confirm the hypothesis. But what she’s not considering is that there’s some work being done in your area and there’s some low-level chemical exposure causing your headache.

“By not asking more questions, the doctor stops at the easiest answer, not the one that actually solves the problem.

“Managers do this all the time: they quickly decide what the problem is, they start attacking that problem. And instead, they should be asking more questions.”

Four ways to switch your approach

How you lead will invariably lean one way or the other, depending on your natural tendencies and career experiences. But it’s not set in stone.

To be able to toggle between styles, you need to train yourself at both ends of the spectrum, says Yokoi.

“If you don’t develop those competencies, you will end up relying on the unconscious, traditional ways of doing things.”

Instead, you need to learn how to be adaptable. To find your leadership range, our experts suggest the following:

1. Understand your weaknesses

Start by practising self-awareness. Yokoi suggests asking yourself the following questions:

- In which work situations do I feel most comfortable?

- In the past month, was there a situation where a particular strength or weakness came out? If so, how did I handle it?

- How could I improve next time?

Once you’ve reflected inward, you need external feedback. For example, Edwards found that outdated biannual performance reviews were not useful for anyone. She revised to a more active feedback model where her team can give and receive feedback on a fortnightly basis.

“The more open you are to learn and grow, the more opportunities you create for others to learn and grow. I’m always learning how to become a better leader,” she says.

2. Evaluate the context

When you have a good handle on your strengths and weaknesses, assess the external environment and factors that may have a business impact, says Yokoi.

“Situational awareness refers to tangible things. [That’s asking], ‘Where is our business today in terms of profit and loss? What are any emerging disruptions? What are our competitors up to?’”

The external environment is also likely to be impacting how your employees are acting in the workplace too. For example, if your business is facing pressures due to supply chain issues, your team may be feeling vulnerable and reacting defensively.

3. Practice empathy

Leaders need to remember they’re dealing with human beings, says Overbeck. A successful leader should not only focus on KPIs, but also on getting the best out of their team. This sometimes means supporting them with the grittier stuff too.

That said, empathy does not come naturally to everyone.

“We have this tendency to miss [emotional] cues, or feel threatened or scared by them, and so we try to ignore them. Or we say, ‘That sort of thing doesn’t belong in the workplace,’” says Overbeck.

“The biggest change we need to make as leaders is to take the focus off ourselves and put it on our team.” – Jennifer Overbeck, Associate Professor, Melbourne Business School

To overcome this, she suggests looking for verbal and non-verbal signals.

“Pay attention to your colleagues’ facial expressions, pay attention to their tone of voice. If they usually respond in a certain way, and then they don’t [in a particular instance], maybe you pause and ask, ‘Hey, is everything okay? We haven’t talked for a couple of weeks. Am I missing something?’”

4. Develop yourself

Once you’ve determined which end of the spectrum you sit at, you need to start practising. But you won’t develop skills overnight. Overbeck suggests dedicating a month to honing new behaviours.

To help this happen, you might consider:

- Conducting daily personal post-mortems.

The way you might set up a retrospective review for your team at the end of a big project, do the same for yourself.

For one week, take time to chronicle your meetings, interactions and your responses. Consider if there were questions you could have asked? Did you draw a conclusion that wasn’t justified?

- Pay attention to your responses

The following week, pinpoint specific behaviours in practice.

“Don’t put pressure on yourself to do anything about it. Just practise noticing,” says Overbeck.

- Identify a catchphrase.

Once you’ve identified behaviours, you might say a catchphrase when you notice them.

“For example, you could say, ‘Can you tell me more about that?’ or ‘Is that something we need to probe more deeply?’”

- Be grounded in the moment.

By the fourth week, you’re typically at a point where you can notice the behaviour and respond in a way that opens up a conversation.

The challenge is now following that conversation while staying grounded.

Leadership is more than a job title and a corner office. It’s an ever-evolving process of adapting, learning and improvising. And don’t be afraid to embrace the contradictions that come with being a leader, says Yokoi. Successful leaders are constantly treading the line between business goals and keeping employees happy.

“It’s the process of embracing those contradictions that will make you more adaptive,” she says. “So the question is, are you going to be courageous and ambitious enough to try and test out something a little bit different?”

This is an edited version of an article that first appeared in the June 2022 edition of HRM Magazine.

Becoming a strong, effective leader is an ever-evolving process. Add more skills to your toolkit with AHRI’s Leadership Essentials short course. Sign up for the next session on 10 October 2022.

Sounds like the Situational Leadership model/theory with a good does of intra and inter personal awareness.

*dose