Lack of clarity and communication is one of the biggest barriers to psychosocial safety. Promoting shared accountability and eliminating ‘blame culture’ could be the solution.

In the last six months, psychosocial safety has transformed from a relatively obscure concept to one of leaders’ top workplace priorities.

The introduction of a new Code of Practice to manage psychosocial hazards earlier this year has prompted many organisations to reconsider their responsibilities when it comes to workforce wellbeing.

This newfound focus on employees’ mental health could not have come soon enough. In a recent report by the Leaders Lab in collaboration with AHRI, almost two in three workers (64 per cent) reported feeling burned out at work, and fewer than one in five reported high levels of psychological safety at work.

“[The new legislation] is about acknowledging that many of our jobs have multiple hazards in them, and [thinking about] how we are going to navigate these with more care for ourselves and each other as we go about our roles at work,” said Michelle McQuaid, Founder of the Wellbeing Lab and the Leaders Lab, in her address at AHRI’s 2023 National Convention and Exhibition last month.

According to the Leaders Lab’s research, some of the most common psychosocial hazards experienced by employees include harassment, poor supervisor support, unachievable job demands and inadequate reward and recognition.

Interestingly, the top source of psychosocial risk cited by survey respondents was a lack of role clarity. This could indicate that employees are in need of clearer and more frequent communication from managers, but are hesitant to reach out and ask for it.

This is a tricky issue to address, said McQuaid, given that we are not naturally inclined to be vulnerable and share our struggles and concerns with others for fear of blame or judgement.

“We spend all of our day in that state of heightened anxiety about what other people are thinking about us,” she said. “What did they say about us? How are they judging us? How is that impacting our job security, our career prospects?

“The idea that we might be a little vulnerable, a little embarrassed, a little out of our comfort zone or perhaps being judged by somebody else actually lights up the same parts in our brain as though [we had fallen] off a scooter and fractured our elbow. It’s painful.”

In order to effectively identify and address the psychosocial hazards that employees are experiencing, leaders have a responsibility to cultivate an environment where hazards are collaboratively recognised and handled. This requires helping your people shift from a blame culture to a culture of curiosity.

Shifting away from blame culture

In our fast-paced, hyperconnected world, the workplace has become more than just a physical space where we perform tasks; it’s a complex ecosystem of social interactions, expectations and, unfortunately, judgements.

“Our brains are natural judging machines, especially when it comes to our social interactions, to try to keep us safe and avoid pain. So we tend to rush to mind-read each other, and we leap to conclusions about what people are thinking, feeling and doing rather than slowing down and asking questions,” said McQuaid.

As a result of this, faced with the reality of the mental health hazards facing their employees, leaders might instinctively look for a scapegoat to ‘blame’ for their presence.

However, McQuaid stresses that there should be no shame or finger-pointing in flagging and managing these hazards, since the fact that they exist is not necessarily a sign of intent or negligence on the part of the employer. What’s more, all employees, including leaders and HR, are subject to these psychosocial risks. Therefore, managing them needs to be an open and collaborative process to be successful.

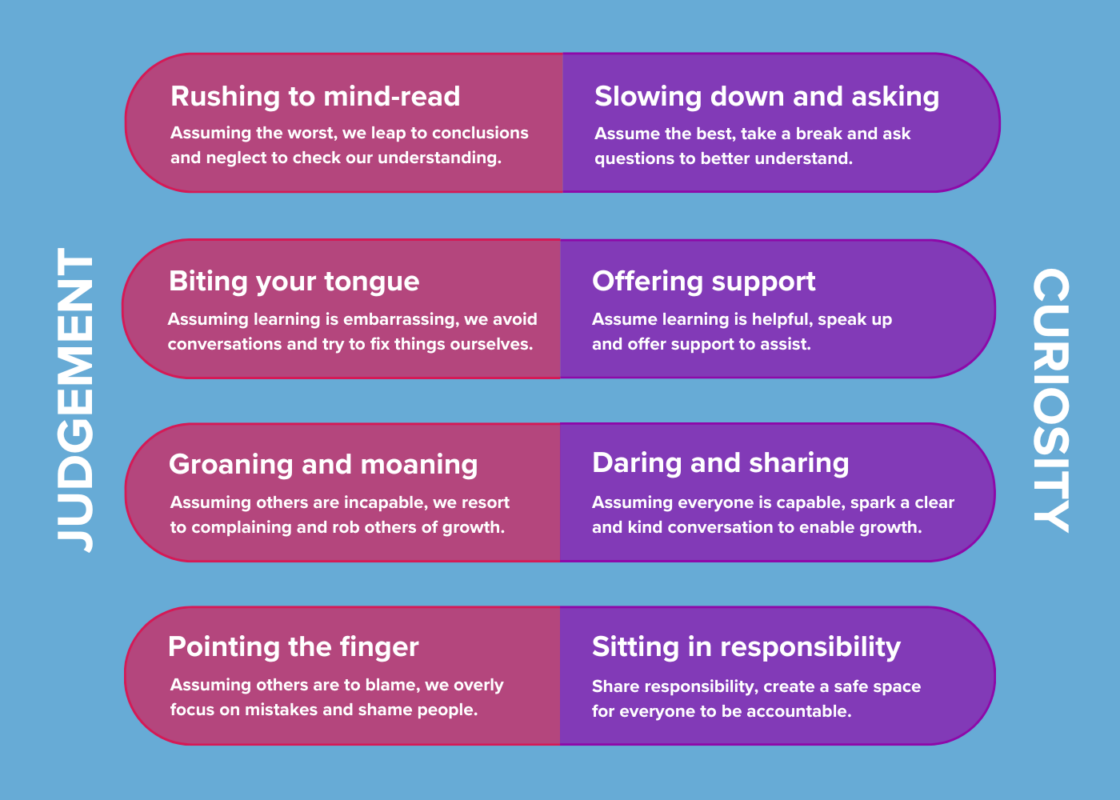

To aid this process, McQuaid and her team have leveraged their research to identify four management behaviours that can lead to blame culture, and the changes they can make to promote psychosocial safety:

This visual was adapted from Michelle McQuaid’s NCE presentation on the Leaders Lab research. View the full report here.

“As leaders, I think we have to lead the way and show that vulnerability is going to be valued and appreciated,” she said.

Cultivating shared accountability

With their new responsibilities to manage psychosocial safety coinciding with a slew of other legal reforms and changes to the way we work, it’s no surprise that our time-poor leaders are grappling with mental health issues of their own.

According to the report, 69 per cent of leaders reported feeling burned out, compared to 54 per cent of team members. What’s more, 91 per cent of these leaders reported they had been feeling burned out for some time or longer.

“Our brains are natural judging machines, especially when it comes to our social interactions, to try to keep us safe and avoid pain.” – Michelle McQuaid, Founder of the Wellbeing Lab and the Leaders Lab

This makes it all the more crucial to ensure that psychosocial safety is looked at through an organisation-wide lens.

“There is a systems lens and a collective responsibility,” says McQuaid. “While the code is clear that ultimately the organisation is going to be considered [accountable for] doing everything reasonably practicable, at the end of the day we all want to go to work, do good work with good people and go home feeling [good]. So, psychological safety needs to happen at a ‘me’, ‘we’ and ‘us’ level.”

The ‘me, we, us’ framework was devised by Dr. Aaron Jarden, Associate Professor at Melbourne University. The framework breaks down the micro- and macro-interventions needed across the organisation to support wellbeing, as follows:

1. The ‘me’ level.

The ‘me’ level focuses on the individual employees and the things they can do at a personal level to improve their wellbeing.

These tend to require little, if any, resources from their organisation. For example, it might include conducting self-care activities outside of work.

“When we feel safe within ourselves, we’re much more likely to also feel safe with others,” said McQuaid.

2. The ‘we’ level.

This level centres around the relationships between people in the workplace. It might be an employee’s relationship with their manager, their team or others they interact with on a regular basis.

By fostering high-quality connections within these relationships, HR can create a culture where employees feel safe to come forward to express concerns or ask for support. Strengthening these connections can also mitigate against ‘blame culture’ by creating a sense of shared responsibility to guard psychosocial safety.

3. The ‘us’ level.

The ‘us’ level refers to a whole-of-organisation approach. This may involve doing a wellbeing or culture audit and committing resources to establish organisation-wide mental health initiatives.

Leaders should remember that, although there are measures that individuals and teams can take to support their wellbeing, the buck stops with them when it comes to tackling psychosocial hazards. Simply encouraging employees to practice self-care is not enough to satisfy legal requirements and the emotional needs of the workforce. Instead, they should focus on creating a process where employees feel safe to help the organisation help them.

“Psychological safety is simply that shared belief that it’s safe to speak out, to take risks, to learn alongside each other,” said McQuaid.

“It’s our willingness to be candid and vulnerable with each other and the belief that that is going to be valued, respected and reciprocated, rather than punished.”

Want to upskill your entire team in Mental Health First Aid? AHRI’s short course is designed to equip your team with these critical skills.