Landmark changes to paid parental leave policies are in the works. Here’s what that means for HR.

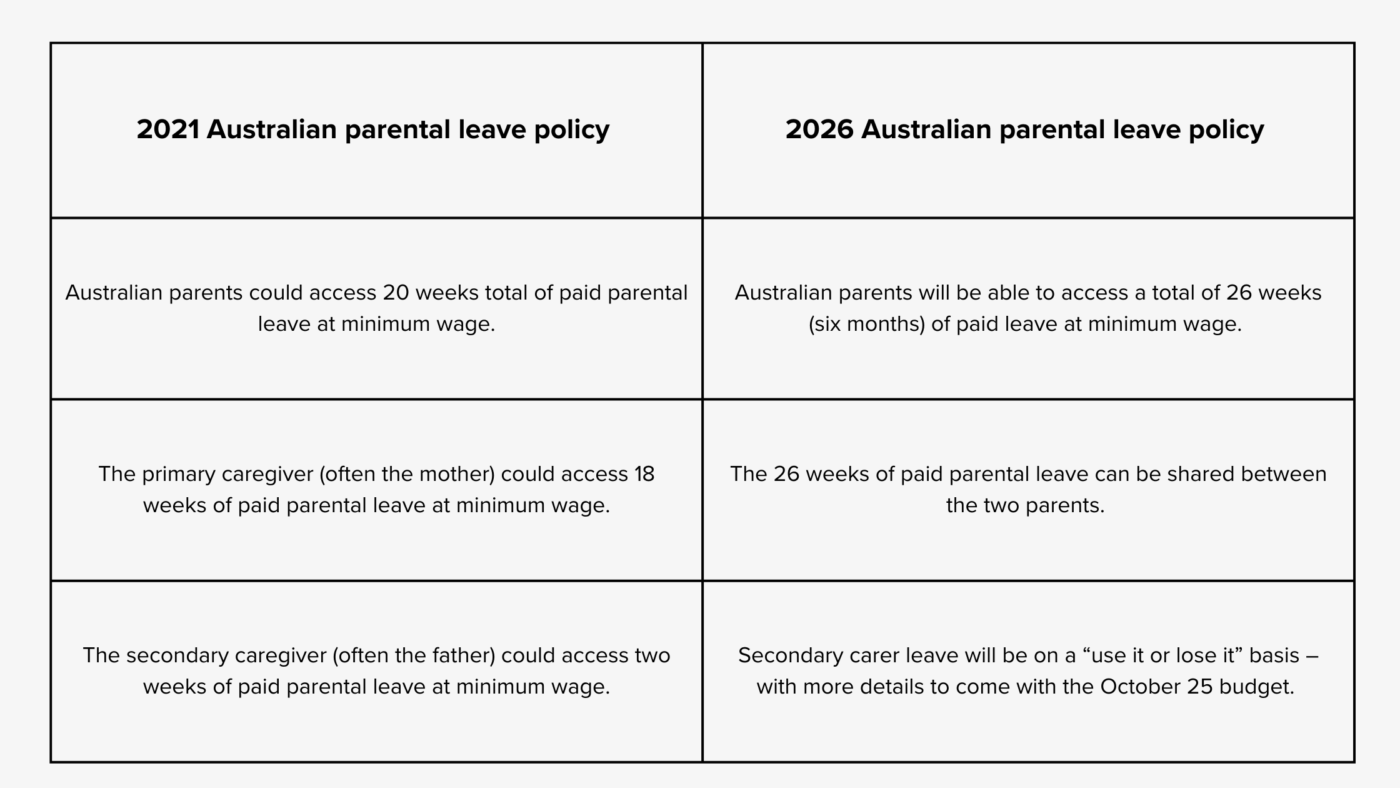

On October 15, the Albanese Government announced plans to extend paid parental leave from 20 weeks to 26 weeks by 2026. Extra leave will be staggered, with an extra fortnight of paid leave added each year from July 2024 until 2026. The new policy won’t restrict which parent can use the leave or the duration they can take within the 26 weeks. Single parents will be able to take the entire 26 weeks.

The first meaningful policy change in 11 years

Before this announcement, Australian parents could access 20 weeks of Commonwealth-funded parental leave. Eighteen of them were allocated to the ‘primary carer’ and the remaining two were allocated to the ‘secondary carer’.

The current system has many implications, especially when it comes to entrenching traditional gender roles, says Dr Leonora Risse, Senior Lecturer in Economics at RMIT University who specialises in gender equality.

“In offering a more generous amount of leave allocation for fathers or partners, it will make caregiving less one-sided, meaning we’re fostering more gender equity at home.

“This matters because we know that if more fathers are involved in parental leave, that is a boost for women’s full-time labour force participation. That’s going to help support women’s economic security over the longer term.”

How Australia stacks up with the rest of the world

“Australia has long lagged behind the rest of the world when it comes to paid parental leave,” says Dr Risse.

“It has been resistant to building it into its government-mandated policies. For many decades, the mantra was that they didn’t want to interfere with household decisions.”

Just look at the numbers. The OECD average for paid parental leave is 51 weeks, whereas Australia’s current policy sits well below the average, at 18 weeks. And it’s a continuing trend – Australia was the second-last OECD nation to implement a national paid parental leave scheme.

“A lot of other countries outside of the OECD, across Asia or South America and Africa, are further ahead in this space too,” says Dr Risse. “Australia is really playing catch-up here.”

Baby steps towards pay equality

“Parental leave means that you’re enabling women to return to the workforce, rather than to drop out completely,” says Dr Risse.

“That supports their overall lifetime earnings and it means there will be more women able to return to work at mid-career levels and move into senior roles that are associated with higher pay.”

Read HRM’s article on ‘greedy work’ and how it holds women back.

Uneven parental leave policies can also contribute to workplace discrimination and Australia’s gender pay gap.

A 2022 report by the Australian Council of Trade Unions found that:

- Women’s participation in the workforce continues to lag behind men (62.2 per cent compared with 70.8 per cent)

- Women account for 68 per cent of part-time workers and 53 per cent of casuals.

- Part-time workers are likely to have fewer opportunities for training and promotion.

- Men account for only 6.5 per cent of all primary carer’s leave taken in Australia.

“If you can rebalance the distribution of caregiving at home, it’s a lever that enables women to advance further in the paid workforce and helps correct those gender gaps in the workforce,” says Dr Risse.

Take it a step further

At last month’s Jobs Summit, increasing leave entitlements was a key recommendation for boosting participation in the workforce and economic growth.

In its media release on the policy change, the Labour Government also recommended companies view these policy changes as a baseline, citing employers across Australia who are competing to offer working parents the best possible deal.

The minimum wage sits at around 47 per cent of average full-time earnings in Australia, says Dr Risse.

“We know if more fathers are involved in parental leave, that is a boost for women’s full-time labour force participation. That’s going to help support women’s economic security over the longer term.” – Dr Leonora Risse, Senior Lecturer in Economics at RMIT University

“There are reports that some men might not take [the leave] because it’s basically a pay cut for them. They might not be able to financially get through that period without that full income.”

To encourage men to take parental leave, Dr Risse says employers could offer wage replacements or make additional contributions to an employee’s superannuation.

Another important way HR can encourage men to use their parental leave is through culture and leadership training.

“There’s a huge role for HR professionals here to work in conjunction with organisational leaders is to shift the culture surrounding men taking leave,” says Dr Risse.

Read HRM’s article on men’s experience of ‘flexism’ in the workplace.

“A lot of fathers report feeling that there’s a negative stigma surrounding taking leave and they’re concerned that it could negatively affect how they’re perceived in the workforce.”

Dr Risse says it could come down to coaching senior executives to create a more encouraging atmosphere.

“There need to be assurances in place that any mother, father, parent or caregiver of any kind who chooses to take leave for caring purposes can be assured that there are no penalties or repercussions to their career opportunities.”

Another approach she suggests is to rethink KPIs. Where a manager or supervisor normally has quantifiable deliverables or outputs, these could instead be shifted to be more people-focused.

She suggests expanding those KPIs to also include supporting the holistic wellbeing of staff. Then it legitimises a manager’s decision to support an employee and comes at no cost to them because they’re delivering their performance indicators.

This is HR’s opportunity to do better

We know that organisations with more generous parental leave packages see higher retention, better recruitment outcomes and increased productivity.

Especially in a skills shortage, signalling to your employees that you care about them is key.

“Offering paid parental leave is a way of signalling to your employees that [your company] acknowledges the importance of balancing work and family, and where your value system lies,” says Dr Risse.

But, she stresses, an employer’s role in paid parental leave should go beyond the strategic benefit. This is HR’s time to play a role in levelling the playing field.

“There’s an opportunity for us to make a big jump forward here and shift the narrative.

“We need to think about [parental leave] alongside the principles of equality and human rights as well.

“Remember we’re talking about people, you want to help them flourish and feel respected and have the dignity of knowing that your caregiving role is appreciated and recognised by your employer. It’s not just a way to improve your bottom line.”

More details about paid parental leave policies will be delivered with the budget on 25 October.

Want to create more equitable workplace policies or enhance your existing parental leave policies? HR’s short course on developing and implementing policies and procedures will equip you with the right skills.