There’s who you are and there’s how you are perceived. At work, neither of those things remain the same forever.

Tim Hessell had a high-flying career as an HR executive when the global financial crisis hit. He was in his mid-50s and possessed a strong set of skills across HR, change management, business and leadership, acquired in a career spanning three decades. And yet he found himself unemployed.

He took up contract work until the contracts became fewer and shorter. He attended numerous job interviews, but heard the same rejections again and again: ‘You’re overqualified’; ‘You’re not the right fit’; ‘Your skillset is out of date’.

Anxiety and self-doubt set in. Maybe it was him, he thought. Maybe his skillsets were wrong, or perhaps he wasn’t going for the right jobs.

But looking around, he realised the same thing was happening to his similarly-aged peers. Contacts in the outplacement industry confirmed that mature-aged clients with extensive experience were considered almost unemployable in Australia at senior levels.

Ageism is prevalent in the Australian workforce. A 2017 study by the University of South Australia found that one-third of Australians had experienced age-based discrimination while employed or looking for work in the past 12 months.

But the assumptions made about older workers – that they can’t learn new skills, or their health is fragile – don’t stand up to scrutiny, says professor Carol Kulik, a senior researcher at the university’s Centre for Workplace Excellence. Older workers tend to be more loyal than younger workers, less likely to change jobs and generally have excellent attendance, she says. “They aren’t a drain on their employer at all.”

Age is an identity shift that happens to us all, and yet age diversity is not a priority for most businesses. “We need teams of all ages because different age groups bring different skills and perspectives,” says Fiona Krautil CPHR, a diversity and inclusion specialist, and founder of Diversity Knowhow. “But age is just not on the strategic agenda.”

Managing identity at work

If diversity is about creating a mix of people that reflects the community and provides the broadest available talent pool, then inclusion is about how to make that mix work.

Inclusion makes people feel like they belong, says Krautil, so they can bring their authentic self to work. In workplaces that aren’t inclusive, employees may bring their professional identities to work, but conceal their social identities, highlighting their outsider status and diminishing their capacity to contribute.

An inclusive culture can help people navigate the shifts in identity that most of us experience in our working life – whether it is growing older, returning to the workforce with a disability, or ‘coming out’ at work.

Twenty years ago, Robbie Robertson, experience design partner at Deloitte and national partner sponsor of GLOBE, Deloitte’s LGBTI network, was working at a company in London where his boss, a “very old-school, very blokey” manager, frequently made homophobic remarks. It created a hostile environment that made Robertson feel he had to check himself constantly at work. “I wasn’t bringing my personality to work at all.”

When his boss saw him out with his partner one night, the bullying started in earnest, which caused Robertson to suffer “crippling” anxiety every Sunday night at the prospect of going into the office.

Eventually, he came out to the company’s “very progressive” managing director, who quickly put an end to the bullying. Robertson instantly felt liberated.

“I flourished. It wasn’t until after I came out, that I realised how much energy I was spending on not being myself… and how much better I was able to focus on doing good work.”

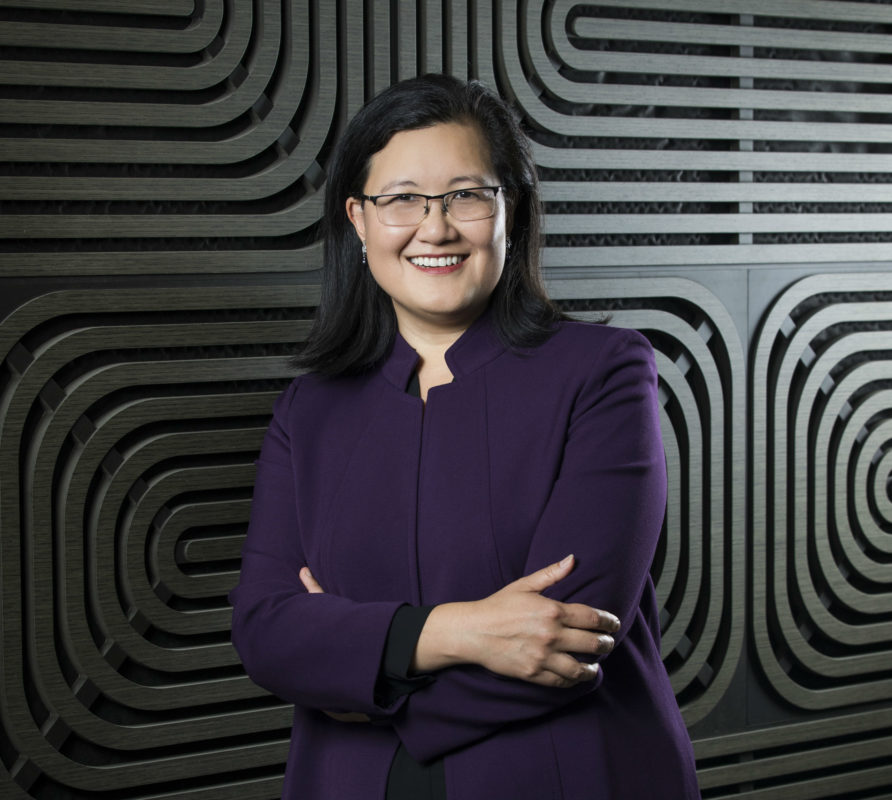

Like Robertson, Ming Long, a non-executive director who is the current chair of AMP Capital Funds Management Limited, has felt compelled to censor her identity at work.

Long, whose family moved to Australia from Malaysia when she was 10, became the first woman from an Asian background to lead an ASX-200 listed company when she was appointed CEO of Investa Office Fund in 2014. “I didn’t bring my true self to work for a very long time,” she says. “I learned over time to save my true self for the weekend.”

She is a self-declared introvert and doesn’t fit the mould of the typical white, male and extraverted leader. Nor is she the stereotypical “meek and quiet” Asian woman. “It irritates some people. When you’re the ‘other’, you’re constantly battling against the majority’s expectations of how you should be.”

Long, who is deputy chair of the Diversity Council of Australia, argues that it’s not up to minorities to change society’s attitudes. It’s unreasonable to expect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – who represent 3 per cent of the population – to overcome the prejudices of the remaining 97 per cent, she says. “The responsibility rests with people who sit within that status quo.”

“I flourished. It wasn’t until after I came out, that I realised how much energy I was spending on not being myself… and how much better I was able to focus on doing good work.” – Robbie Robertson

When Identity empowers

In 2013, Saran Chamberlain was the business manager of 2ic Software, a growing pallet management software company based in Adelaide. It was a job she loved.

One morning, she suddenly lost feeling in her left side, collapsed and was taken to hospital. The next day an MRI revealed that she’d suffered a stroke. “I couldn’t walk,” she says. “I had no feeling in my arm – it was as though it didn’t exist.”

Her life was instantly upended. Eight days in hospital, three weeks in rehab and months of therapy followed. She battled with her loss of independence and the extreme fatigue the stroke caused. “For the first 12 months, I probably slept at least 70 per cent of the time.”

She was determined to return to work even though her capabilities were now vastly different. “Pre-stroke Saran was Speedy Gonzalez. Post-stroke, I was barely able to move at a snail’s pace,” she says. “Even the effort of getting up and getting dressed with one hand was a trial in itself.”

Her boss was supportive, and colleagues welcomed her back, but she still felt pressure to be her old work self. “I was expected to still be me, and I wasn’t. I had to say to people, ‘There will be times when I can’t do the things you think I can do, so I will have to say no.’”

“For me, not to work would be to take away my whole identity.” – Saran Chamberlain

In 2014, she left 2ic Software and started her own business, before taking a permanent role at a different company in November 2018. “I know I have to pace myself,” she says. “If I learn something new or if I’m doing multiple processes at the same, I have to realise that by the afternoon, I will need a sleep.”

Depression, common among stroke survivors, is a constant presence. “I can quite easily be really down and have really dark days, but I find that coming into the office helps.” Work has been crucial to her recovery. “For me, not to work would be to take away my whole identity.”

It’s a sentiment echoed by Dr Dinesh Palipana, who was two years into his medical degree at Griffith University in Queensland when a car accident in 2010 left him with quadriplegia. He spent eight months in hospital, first in intensive care and then in rehab, learning how to breathe, sit and move around unaided.

Although his recovery was arduous, Palipana remained determined to resume his medical degree. “I knew that if I didn’t finish it, I’d regret it for the rest of my life,” he says.

Key supporters helped him pursue his dream – first and foremost his mother, but also Griffith University’s dean of medicine and clinical sub-dean, who made the unprecedented decision to allow Palipana to resume his position in the course in 2015.

But he was also met with resistance from some quarters. Soon after the university accepted him back, Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand issued a new set of guidelines for students’ physical requirements that, if enforced, would have precluded him from entry to a medical degree.

In 2016, he became the first person in Australia with a spinal cord injury to graduate from medicine – and the only student in his cohort that Queensland Health did not immediately offer an internship. He waited six months until he was offered a position at Gold Coast University Hospital, where he currently works in the emergency department – “a close-knit team” that he says has been very supportive.

It helped that he and the hospital had the aid of government initiatives that support employees and employers in the disability space. Through JobAccess and the Employment Assistance Fund, electric wheels were secured for Palipana’s wheelchair, and when he started, an occupational therapist came in to assess the situation and offer suggestions.

Interactions with patients are always positive, Palipana says. Any doubts about his ability tend to come from administrators or the odd senior doctor – such as the specialist who questioned his capacity to perform basic tasks such as typing or doing night shifts, assumptions he says are unfounded. “I can type 55 words a minute with my knuckles and I do night shifts all the time.”

A founding member of Doctors with Disabilities Australia, Palipana was a keynote speaker at TEDxBrisbane and Stanford Medicine X in 2018, and Gold Coast Hospital and Health Service’s Junior Doctor of the Year. In 2019, he received the Medal of the Order of Australia for his services to medicine.

Nine years after his accident, it’s his passion for medicine that gives him purpose. Life with a spinal cord injury comes with a unique set of challenges – just getting up in the morning can take hours. “Because I’m doing something that I love, I’m willing to go through it.”

Priorities and methods

To make inclusion work, organisations must firstly identify diversity and inclusion as a business priority, says Krautil. In a volatile and complex world, she says, no one person can solve all the problems any more – we need teams with diverse perspectives, or we risk groupthink.

Diversity without inclusion costs money, but diversity with inclusion delivers innovation, improved problem-solving, higher engagement and profit.

Inclusion has moved beyond affording select groups special treatment, says Krautil. Instead, organisations must create culture and systems that deliver equity for everybody, “not just the usual suspects of the in-group”.

At Deloitte, diversity and inclusion policies acknowledge the impact of intersectionality. The LGBTI network collaborates with groups such as Women@Deloitte and Deloitte Dads to examine how diversity and inclusion initiatives can cater to employees’ multifaceted identities. “I’m a gay man, but I’m also a dad,” says Robertson. “People can wear multiple hats and be different people at different points of the day, week and year, and I think that’s important to acknowledge.”

Every year Deloitte compiles a list of some of the top LGBTI leaders in Australia, called Outstanding 50. “It’s amazing to hear their stories and share them with our teams at all different levels,” says Robertson.

Flexibility factor

To be successful, inclusion needs flexibility. A policy that is “relevant for every identity and age group”, says Krautil.

For Chamberlain, flexibility was crucial to her return to work. Resuming her role as business manager was out of the question, but her CEO at 2ic Software allowed her to complete admin tasks and “bits and pieces” around the office, working for a few hours at a time. “I was willing to do any role, just as long as I could come in.”

The flexibility older workers require is different to working parents’ need to accommodate school drop-offs and pick-ups. Older workers have different priorities: the flexibility to redesign roles, care for grandchildren or a sick spouse, or take off chunks of time to travel.

Kulik believes that businesses that are serious about age diversity should introduce age-specific management policies. Phased retirement, job redesign, career counselling, and even featuring older people in recruitment advertising, “sends a really positive signal that the organisation values older workers.”

Hessell, who is studying a PhD in organisational ageism, believes age discrimination at work is part of a bigger issue. “The only narrative we have about age in the community is one of decline. There is no alternative narrative to reimagine ageing as a positive experience, and all the things you learn and gain out of life and work in terms of resilience and self-awareness.

Hear from Paralympian Kurt Fearnley and Ming Long as they discuss inclusion at AHRI’s Diversity and Inclusion Conference this May. Registration closes Friday 3 May.

The question was asked in an industry interest group about the pros and cons of integrating Inclusion and Diversity into the recruitment process and or the pros and cons of having a role in recruitment designated to recruiting candidates with Diversity and Inclusion characteristics. What are your thoughts on the topic?

[…] different reasons for doing so. They might need time off to care for children; perhaps they’re recovering from an injury; or, like my dad, they might want to set themselves on a new path. Whatever the reason, there’s […]