Australians are living longer, with 40 per cent of the population estimated to be over 55 by 2050. Yet, HR’s perceptions of what it means to be an “older worker” is getting younger. What risks does it raise for organisations and Australia more broadly?

The Australian HR Institute and Australian Human Rights Commission’s latest joint research paper into older and younger workers in Australia reveals some concerning trends.

Almost a quarter (24 per cent) of HR practitioners who responded categorised “older” workers as those aged 51 or over. Just two years ago, the proportion was 10 per cent. Further, nearly 1 in 5 (18 per cent) said they are not at all open to hiring people aged 65 or over.

And it’s not just older workers who are the object of ageism. Younger workers can experience it, too. Only three per cent of respondents said they perceived younger workers as having professional knowledge and experience.

At the same time, however, more than half of HR practitioners (55 per cent) surveyed reported facing difficulties with recruitment.

Employers could benefit from tapping into the skills, knowledge and experience of workers of all ages – while gaining the social and business advantages of an inclusive, diverse and engaged workforce.

So, why and how is ageism creeping earlier into HR-related decisions? What risks is this bias creating, for both companies and Australia more broadly? And how can HR practitioners combat ageism and make the most of the skill sets of the entire workforce?

What’s driving ageism in HR?

Ageism isn’t just a problem for HR; it’s a social, cultural and structural issue.

In AHRI’s survey, 69 per cent of respondents reported no difference in job performance between older and younger workers. Yet, only 56 per cent reported being open to hiring workers aged 50-64, and only 41 per cent were open “to a large extent” to employing those aged 15-24.

The implication is that unconscious, age-related bias remains widespread – driven by long-held assumptions.

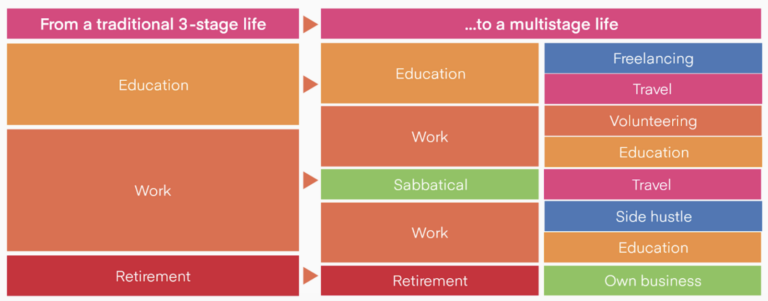

“We’re living in an era of multi-stage careers,” says Alison Hernandez, who co-founded ReCreate 100 with Catriona Byrne, which is an organisation designed to support individuals and organisation to embrace the longevity of our lives and careers.

“People in their 50s, 60s, and beyond are reinventing themselves professionally. They’re reskilling and pursuing new qualifications, starting businesses and side hustles, and taking on leadership roles in new industries.”

Additionally, classifying workers according to age in the first place might not actually be the best idea.

“Age 51 represents a chronological milestone, not a career stage. Someone might be early-career in a new field, while another is transitioning to their third act.” – Catriona Byrne, co-founder, ReCreate 100

“Ironically, you become ageist as soon as you focus on age,” says Byrne. “Rather than reinforcing assumptions, we need to fundamentally change how we approach this topic – by focusing [not on age], but on attitude, aptitude and contribution.

“Age 51 represents a chronological milestone, not a career stage. Someone might be early-career in a new field, while another is transitioning to their third act.”

Read this case study on how Bunnings is creating an age-inclusive organisational culture.

How does ageism in business manifest?

AHRI’s research found that ageism manifests in both recruitment and retention.

In recruitment of older workers, two of the main perceived barriers identified by respondents were candidates’ expectations of high salaries (32 per cent) and having ‘too much’ experience (28 per cent).

For younger workers, these were candidates’ perceived lack of experience (57 per cent) and expectations of high salaries (43 per cent).

These perceptions have been playing out in the outcomes of recruitment processes. Only 57 per cent of HR practitioners surveyed said they had recruited workers aged 55 and over in the previous 12 months – down from 68 per cent in 2023.

In better news, many have taken steps to support age diversity in recruitment. These include ensuring recruitment content is age-inclusive, positioning job ads to attract diverse age demographics and taking a skills-based approach to hiring.

When it comes to retention, many respondents reported offering age-inclusive initiatives such as flexible working hours (80 per cent), part-time work (78 per cent) and carers’ leave (72 per cent).

However, only a small percentage said they went further with options for phased retirement (35 per cent), job-sharing (28 per cent), intergenerational mentoring (18 per cent), career planning (17 per cent) and digital capability upskilling (16 per cent).

What risks does ageism present to both businesses and Australia more broadly?

Given that 56 per cent of businesses are having difficulties with recruitment, the first, and most obvious, risk of ageism is an inability to tap into the skills and potential of the entire workforce, putting organisational and national productivity growth at risk.

This risk may emerge very early in the recruitment process – even before workers apply. For example, Watermann et al’s 2016 study found that older workers who experienced age-based discrimination were more likely to withdraw from job searching.

According to AHRI’s research, a lack of older applicants was the main barrier to employing older workers, reported by 36 per cent of respondents.

Once older employees are in the workforce, ageism can lead to a failure to provide important, engaging work that aligns with an organisation’s goals and drives innovation. Forty one per cent of employees’ time is spent on “low-value, misaligned or duplicative work”, according to a 2025 study by Beamible.

“Rather than assuming older workers can’t adapt, we should be redesigning roles to focus on high-value, meaningful work for all employees,” says Hernandez.

“If employees are to thrive in a multi-stage career, learning and development initiatives must reflect their evolving needs. Many organisations tend to over-invest in early-career development and neglect mid- and late-career learning.

“The longevity economy represents a $35 trillion+ global market.” – Alison Hernandez, co-founder, ReCreate 1oo

“As career transition experts often observe, employees with decades of service might leave a role with little professional development or support because nobody thought to ask what they needed along the way.”

There are also important inclusion gains that businesses miss when they exclude certain cohorts due to their age.

For example, intergenerational teams are 25 per cent more engaged and perform better than their counterparts in creativity and problem-solving, according to this study by McKinsey.

Further, when older workers leave, their experience often goes with them. Only 13 per cent of organisations consistently capture the knowledge of older workers upon exit, according to AHRI’s research.

These organisation-level risks raise significant risks for Australia more broadly – particularly given that, by 2050, more than 40 per cent of the population will be over 55.

“The productivity challenge facing Australia cannot be solved without optimising labour force participation across all demographics,” says Byrne.

Australia’s ageing population could present challenges for economic growth, living standards and government finances, reports the federal Treasury.

However, tapping into older workers could help with overcoming these challenges, ensuring Australia optimises their contribution to the economy – by, not only working and paying taxes, but also spending.

“Fifty per cent of consumer spending comes from the 50+ demographic,” says Hernandez, referring to research by AARP. “The longevity economy represents a $35 trillion+ global market.”

Learn how to create an age-inclusive culture with AHRI’s introduction or advanced-level DEI practice short course.

How can businesses combat ageism?

To begin, it’s important that businesses stop thinking about employees’ potential through the lens of their age.

“Instead of age-based categorisations, organisations should focus on attitude, aptitude and contribution,” says Byrne. “These factors vary enormously within any age group. There are 25-year-olds who resist change and 65-year-olds launching innovative startups.”

Attitude includes a worker’s willingness to learn, adapt and collaborate. Aptitude refers to relevant skills and the capability to develop new ones. Contribution is defined as the capacity to create value.

This means, not asking how to ‘manage older workers’, but how to think strategically and holistically about a multi-generational workforce, says Hernandez.

“How can age inclusion drive sustainable productivity? What role design supports multi-generational teams? How do we create psychologically safe workplaces that enhance performance across all demographics?”

AHRI’s report shares actionable insights in four areas: recruitment, lifelong learning and training, health and wellbeing, and inclusivity.

In recruitment, these include:

- Using age-neutral language in job ads;

- Avoiding chronological requirements, such as date of birth and graduation years, in applications where unnecessary;

- Focusing on capabilities, achievements and skills;

- Training hiring managers in unconscious bias;

- Ensuring diversity in recruitment panels;

- Auditing recruitment tools, such as AI, for biases; and

- Monitoring data for implicit bias.

In facilitating lifelong learning and training, organisations should:

- Offer career-transition support for mid-late career workers;

- Support cross-generation mentoring;

- Foster a coaching culture that emphasises continuous learning; and

- Evaluate training uptake by age demographics, then adjust strategies if age-based gaps emerge.

Strategies for making health and wellbeing programs more age-inclusive include:

- Providing mental health resources sensitive to workers’ needs throughout their life-cycle, from early career stress to midlife burnout;

- Enabling flexible work arrangements and options that cater to different life stages; and

- Offering career-life coaching that addresses work-life balance and supports transitions such as return-to-work, mid-career shifts and retirement preparation.

To promote inclusivity, HR practitioners can:

- Gather feedback by age demographics;

- Create and support age-diverse employee resource groups and networking groups focused on age inclusion and intergenerational collaboration;

- Encourage age-inclusive innovation teams that contribute to strategy and transformation projects; and

- Execute initiatives that combat age-related stereotypes and stigma.

“Australia’s productivity commission recognises that we won’t solve our productivity challenges without significantly increasing labour force participation,” says Byrne.

“Overlooking a quarter of the potential workforce based on arbitrary age thresholds is economically unsustainable.

“The conversation needs to shift from managing age differences to leveraging the full spectrum of talent, experience and capability that a multi-generational workforce offers.”

Completely agree with the article which I wish could be passed onto recruiters and talent acquisition consultants who are increasingly acting as gatekeepers by applying their own often misguided, subjective and unfounded biases that makes it quite impossible for many to get even to first base. They appear to be constantly seeking the goldilocks group between 30-45 then complain bitterly of a skills and talent shortage of their own making. The requirement for dates related to birth and educational accomplishments should be banned as a good first step to encouraging the objective assessment of the skills, attributes, attitudes and capabilities… Read more »

At least 44% of recruiters are clearly under 50. Consider. Anyone older than 50 had to adapt when cell phones replaced landlines; learn the internet; learn email; learn vhs then Beta then BlueRay then DVDs then streaming; learn the tech with all appliances; learn migration from paper to database files…just to name a few tech advances. That generation has had to make the most significant technology adaptations than any other. In addition tbey had to adapt to the legislative changes in every sphere of work and life. They survived the GFC and most were redundant at least once. The rhetoric… Read more »

In my experience it hasn’t been the recruiter but the hiring manager or management who has been ageist.

I had a candidate in 2020 when you couldn’t get anyone who had more than enough experience and can with good project references however the employer didn’t want to hire them because of “insurance”.