Sex discrimination commissioner Kate Jenkins, actress and intimacy coordinator Michala Banas and many others share ideas and solutions about how to tackle workplace sexual harassment.

Last week, experts from a variety of industries gathered in Sydney for the Not In My Workplace summit to analyse data, discuss problems and pave a way forward for tackling sexual harassment in our workplaces.

The diversity of the speakers attests to the fact that this is a widespread issue, with people from the media, sports, defense, entertainment, public service, and more in attendance.

Here are some of the highlights.

Where we’ve coming from

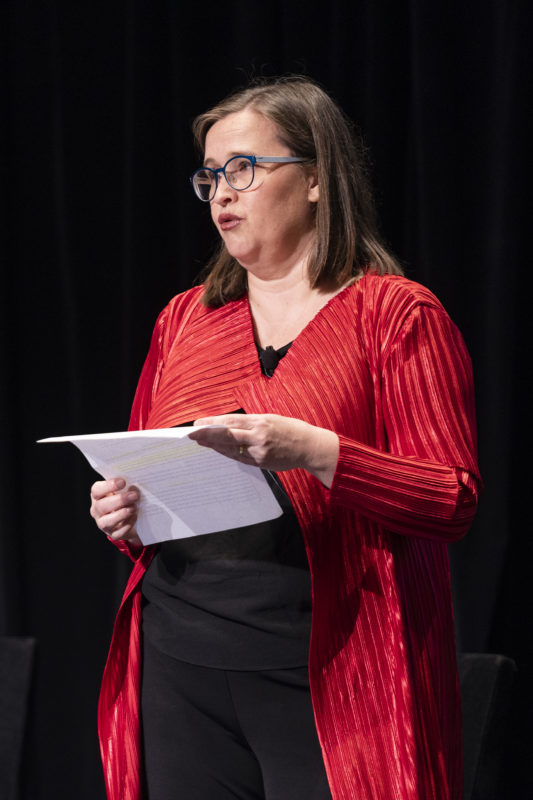

The Australian Human Rights Commission’s (AHRC) sex discrimination commissioner Kate Jenkins set the tone for the day by unpacking the results of the AHRC’s 2018 survey into workplace sexual harassment, which HRM reported on this late last year. This was done in anticipation of the second instalment of the report, due to be released in February 2020, which Jenkins said is solutions-focused and includes government and employer recommendations.

Jenkins talked about the most at risk age group, those aged 18-29, but mentioned that 20 per cent of 15-17 year olds also reported experiences of sexual harassment at work. It’s a shocking statistic. Twenty per cent of people experiencing the workforce for the very first time are reporting instance of sexual harassment. What kind of tone does that set for the rest of their careers?

It’s not just a statistic. Jenkins drew on a submission to the 2018 national survey to convey the harsh reality.

It was from a woman who has had to dodge the unwanted advances of male colleagues for her entire career.

The woman recalled being coerced into private rooms by her manager at just 14-years-old. At 17, she says her boss encouraged her to drink alcohol, and she was told it was part of a company policy to sleep with him. As this woman got older, she moved into the mining industry where she faced further harassment and was often propositioned.

Desperate for a change, she thought a move into the corporate space might provide some respite. But she quickly realised this was “much more insidious than a mine site”.

The culmination of years and years of harassment snowballed into suicidal thoughts, says Jenkins. Here’s the most shocking part of the woman’s submission:

“To avoid going to work, I planned on driving my car into a tree. A few weeks in hospital would mean I didn’t have to go to work.”

Thankfully, she didn’t follow through on the plan. But she did suffer from a psychological breakdown that affects her to this day.

“I can not look men in the eye now. I hope to leave this behind and be me again, but that just seems like a dream.”

This story is heartbreaking, but it’s not unique. Jenkins said it was reflective of many of the submissions the Commission received.

A broken complaints system

Jenkins said Australian organisations need to ensure their complaint systems are compliant, robust and working for the victims, not against them. After a complaint is made the harassment stops 44 per cent of the time, said Jenkins, drawing on the report. But in 43 per cent of cases complainants faced negative consequences, and a few even lost their jobs.

“The legal system works in a way that protects people from being unfairly dismissed but it doesn’t help for those who want to make a complaint,” says Jenkins. “Complaint systems aren’t always looking out for the wellbeing of staff. It’s like ‘you’ve made a complaint and now we need to do a six month investigation’. And sometimes the victims are sidelined.”

The appetite is there from employers who want to do more, but we need to shift the responsibility from the victim to the workplace, said Jenkins.

She suggests we look to things that have worked well in the workplace healthy and safety space.

“When I hear people say ‘we don’t have a problem, because we don’t have complaints. I know that’s just not the case. Harvey Weinstein didn’t have any complaints on his record,” she says.

“The way we work now is drastically different to how we did in 1984 [when sexual harassment laws were first introduced in Australia]. The reality is that we have the gig economy and short term contracts. So the question is, if you’re trying to keep your short term contract, would you raise a complaint? Maybe not.”

Get strategies on how you can prevent sexual harassment in your workplace with AHRI’s e-learning modules on ethics and conduct.

Doing things differently

Also speaking at the summit was award-winning actress Michala Banas. You might know her as Kate Manfredi in the TV show McLeod’s Daughters. But Banas wasn’t at the summit to wax poetically about her star turn in a popular TV drama, she was there to talk about her new role as one of Australia’s only intimacy coordinators.

We know from the AHRC report, the revelations about the troubling behaviour of high profile people in Hollywood (beginning with Harvey Weinstein), and the accusations made against Australian TV presenter Don Burke and actor Craig McLachlan, that sexual harassment is a problem in the entertainment and media industries.

As HRM wrote about in an article on the complaints process at the Sydney Theatre Company during the time when Geoffrey Rush was accused of harassment (the actor won a defamation case against Nationwide News over two articles published about the accusation), there is a high risk of blurred lines and abuse in a workplace where workers are required to kiss and simulate sex. To combat this, it’s becoming best practise to hire intimacy coordinators such as Banas to create boundaries to make sure all intimate performances are carried out with consent at the core.

“There were no rules around consent and agreement [in rehearsing intimate scenes]. I’ve had enough of hearing horror stories. [The entertainment industry] is a very unique workplace, but it’s still a workplace,” said Banas.

She likened her role to a stunt director. When you see something intimate playing out on a stage or screen (that could be a kissing/sex scene, child birth or anything that involves nudity/vulernability), chances are an intimacy coordinator played a role in coordinating that experience with the actors involved.

From her own professional experience, she said often when actors are asked to act out a sex scene it’s thrust upon them in a way that leaves little time for contemplation.

“Often the script will just say ‘and then they have sex’. But we need to be asking questions like, ‘Well, what kind of sex? What positions? Are they taking all their clothes off?’”

In a fast paced production schedule, directors frequently don’t take the time to block these scenes out with these questions in mind, said Banas, so she creates time. She’ll ask the actors to explicitly outline which body parts they are comfortable to have someone else touch and she’ll ensure the set is closed when filming/rehearsing such scenes to avoid any unwanted eyes on the actors.

Banas says her new role has been welcomed with gratitude and relief from fellow actors.

“If there’s an issue, people don’t always feel comfortable going to a producer or a director, but I’m the buffer. People know they can come to me in a confidential way,” she says.

“There was a hole in our industry which, looking at it now, is so obvious. How long have we been telling stories for? Remember when you didn’t have to wear a seatbelt in the car? We’re the car seatbelt.”

Something Banas believes that other industries can take away from her work is to not make assumptions about what people are/are not comfortable doing.

For example, she would never assume that a more experienced actor is more comfortable being touched than an up-and-coming actor. Also, it’s not just women that are the victims in these scenarios, the 2018 AHRC report showed that 1 in 6 men were sexually harassed at work in 2018, so we need to check in with men too.

She encourages employers to think about the buffers they’re implementing in their own workplaces.

Practical tools

In a different session, after tackling some of the big issues, a panel of experts laid out practical tools for workplace change. Here’s a snippet of what they had to say:

- Julie Inman Grant, e-safety Commissioner

Technology-based sexual abuse is on the rise and we need to be talking about it at work.

“Social media surfaces the sad underbelly of the human condition,” said Inman Grant. “It can be a great leveller, and we want people to share their voices, but we need to protect them.”

Creating robust social media policies that protect not just the business but the employee is paramount. Organisations need to include safety by design in social media platforms – much like is done with motor vehicles.

Inman Grant directs people to Women Influencing Tech Spaces (WITS) for more information, including details about social media self-defence tips.

- Natalie Goldman, HR and D&I expert

Goldman thinks most Australian organisations are at an embryonic stage in dealing with workplace sexual harassment effectively. Her advice was to do more to engage men in the conversation.

Looking around the conference, the gender split was about 90/10, women to men. This is reflective of many D&I related events, said Goldman. One way to combat that is to turn these conferences into what’s called ‘Noah’s Arc events’.

The premise is simple – put on an event that both genders should be present for (conversations around D&I, sexual harassment etc.) and make it a requirement that in order to attend, you have to bring someone of the opposite gender.

“This way you have a 50/50 gender split and you can avoid preaching to the converted,” says Goldman.

- Anoushka Dowling, MATE Program Assistant Director, Griffith University

Bystander training is incredibly important in tackling sexual harassment, said Dowling. The first thing people need to realise is that no matter what their status is in an organisation, we are all leaders in some shape or form.

“There are people in your life who will look to you as a leader, and you have to decide if you want to be a positive leader or not,” she said.

“We can disempower ourselves if we walk into a business and think that we need an impressive title to call out bad behaviour.”

You might not think you need further educating on this topic, but most people aren’t yet at a point where calling out bad behaviour is second nature.

“If smoke was billowing out of a building, you’d have an obligation to say something to get people out of the fire. But when it comes to calling out sexual harassment people are unsure what to do,” said Dowling.

Calling out this behaviour should start small, she said. It can begin with not letting sexist jokes or ‘innocent’ sexual comments made towards a colleague pass. Dowling says organisations need to train people how to nip these problems in the bud before the perpetrators take these disrespectful/sexist perceptions out of a social situation, and before they lead to something much worse.

NOTE: A previous version of this article failed to mention that Geoffrey Rush won a defamation case against Nationwide News. We have also deleted a reference Jenkins made to union membership levels in the 90s.

I’m not sure Jenkins’ claim that “most people joined a union” in the 1990s is accurate, and the linked article to union membership would suggest the same. Nor am I convinced that Rush’s successful pursuit of a defamation claim can be held up as an exemplar “that sexual harassment is rampant in the entertainment industry”.

I’m a big believer in bystander training to call out any form of overt discrimination and a strong and approachable HR function unafraid to deal with difficult issues.