Six things to consider if you want to become a better ally.

Disclaimer: The author of this article is not Black, however the advice presented below has been sourced from the Aboriginal and African American community.

If you were on Instagram last week you would have seen people posting images of plain, black squares paired with the hashtags #BlackLivesMatter and #BlackOutTuesday.

The intention of this gesture was to show solidarity with the Black community in a time when global protests are happening in reaction to the tragic death of George Floyd. But good intentions don’t always result in helpful actions. The overuse of #BlackLivesMatter meant important messages from the Black community were eclipsed. The resources and stories they’d poured hours into creating were suffocated by a sea of black squares.

This is a perfect example of how not to be an ally.

To be an effective ally, you can’t just jump on a bandwagon without doing the research to find out what the communities you’re trying to support actually want from you. It’s not a performative, one-off act of solidarity on a national day or after a tragic event in the media. You need to embark on a journey to truly understand the inequality our societies are built upon, and constantly unlearn and challenge racist biases and behaviours both in yourself and in others. It’s a journey with no end point.

Workplace diversity and inclusion initiatives won’t work without employers also training staff in how to be effective allies to their colleagues who belong to marginalised communities.

Below HRM has collated information from the Black community about how to be an effective ally. While this is certainly not an exhaustive list, it’s a good place to start.

1. Understand what privilege means

This is the first part of the journey and it’s here many people get stuck. The tendency to feel defensive when asked to recognise one’s own privilege often comes from not understanding what “being privileged” means.

“Privilege does not mean you’re rich, that you’ve had an easy life, that everything has been handed to you or that you’ve never had to struggle or work hard,” says Franchesca Ramsey, an American activist and YouTube personality. “All it means is that there are some things in life that you will not experience or have to think about just because of who you are.”

For example, in Australia a white person will not get pulled over by the police because of the colour of their skin. And a straight person won’t experience violence because of their sexuality.

While many of the conversations around privilege and inequality are focused on what’s happening in the US right now, it’s important Australians don’t forget to look inward.

Recent data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows Indigenous daily imprisonment rates are over ten times higher (2,589 persons per 100,000 adults) than the national average (223 persons per 100,000). Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander people are also far more likely to die in custody.

You might recognise the phrase “I can’t breathe” as George Floyd’s dying words, but they were also the final words of David Dungay Jr, a 26-year-old Dunghutti man from Kempsey who was sedated and pinned down by six officers in Long Bay Correctional Complex in 2015 for eating a rice cracker in his cell.

“It happened a short drive from an elite university, next to affluent, waterside suburbs,” writes Dr Thalia Anthony, who specialises in Indigenous criminalisation, in an article for The Conversation. “But his horrific death did little to pierce this white bubble of privilege. The media barely blinked. The politicians did not emerge from their holiday retreats. None of the officers involved were disciplined or called to account.”

It’s not just the family of David Dungay Jr who haven’t received justice. Not a single officer involved in the 432 Indigenous deaths in custody since 1991 has ever been convicted. The killing of Black people in and out of police custody is an issue that demands everyone’s attention, but we must not avoid facing our own national atrocities.

2. Learn how to unlearn

The second thing many non-Indigenous/non-Black people struggle with is coming to terms with their own, often unconscious, racist tendencies.

It’s easy to label yourself as “not racist” but it gets more complicated if you want to be “anti-racist” – so, actively and consistently opposing and fighting against racism. This is where many of us (myself included) need to do more work.

On an individual level, that means analysing the oppressive systems you benefit from, looking at the corporations you support that hold Black communities back, deeply analysing your behaviour around Black people (i.e. Have you ever crossed the road when seeing Indigenous person approaching?) and reminding yourself not to sit in silence when witnessing a racist act. Workplaces can assist with the final point by facilitating bystander training on an ongoing basis.

From an employer perspective, this means looking at which businesses you partner with and understanding what they stand for, as well as investigating inequality in the cultural/gender make up of your organisation and challenging unconscious bias in recruitment and career development, among many other things.

3. Prepare for discomfort

In her online resource, ‘A guide to to allyship’, Amélie Lamont, a Black woman, tells the story of someone who she considered to be her ally remaining silent while Lamont was “berated by a racist”. Painfully, Lamont and her “ally” had only recently discussed the power of allyship in situations like the one unfolding before them.

It was an uncomfortable awakening for Lamont. She realised it’s much easier for someone to call themselves an ally than to actually be one.

“When the time came for them to take action, they were more interested in protecting their comfort… Saying you’re an ally looks good on paper, if you’re never taken to task for doing nothing.

Many claiming the word ‘ally’ wear the phrase and ideology like an article of clothing, easily discarded when it’s no longer hip/safe to wear. If only those who are marginalised could cast away their identities with such confidence and ease.”

We should try and see the act of being called out for unconscious racism the same way we view being called out for stepping on someone’s toes, the guide suggests. If someone says “you just stepped on my toe” our initial response isn’t to deny it happened. We swiftly apologise, move our foot and promise to be more careful next time.

Prepare to be called out for getting it wrong or not doing enough. You might feel embarrassed, defensive or hurt, but that’s part of the process. If you’re committing to being an ally, you’re committing to receiving feedback on how to do it properly.

4. Ally is a verb

As the old cliche goes, actions speak louder than words. It’s not enough for a workplace to be reactive when it comes to racism; true allies proactively try to end inequality.

For example, in 2018 HRM reported on a reactive workplace response. Starbucks shut down all of its US stores to conduct an afternoon of racial bias training following an incident where a staff member called the police on two Black men sitting in the store.

The employee told the police the men were trespassing when, in fact, they were patrons waiting for a friend to join them. At the time HRM wrote, “Is this a real cultural change or just something done to quell a PR crisis? There’s a strong argument that it’s the latter.”

An example of an organisation taking a proactive approach to combat racism would be one that regularly engages in bias training and follows up with tangible policy and process changes.

There are lots of options out there for organisations who want to become more actively diverse and inclusive. They include privilege walks, creating Reconciliation Action Plans, talking to experts about how to make your onboarding more inclusive, country-specific training, diversity recruitment drives and internship programs, culturally specific leave policies and fostering a culture that calls out racist behaviours, be they subtle or overt.

Many organisations have been criticised for being too soft or generic in their public statements of support/solidarity. The advice from some in the Black community is to sit with that discomfort. If someone says what you’re doing isn’t enough, try to do better.

And if your organisation is going to release a statement, make sure it’s just a first step. Next, consider donating to organisations that support Indigenous and other minority communities (we’ve shared a suggested list at the bottom of this article). Review and create policies in your workplace that protect and empower staff from all backgrounds. Focus on injustice all the time, not just when anti-racism is trending. When the international attention shifts, which it inevitably will, keep having important and difficult conversations.

5. Do the work yourself

In our personal lives, some Black activists have stressed it’s important we resist the urge to contact our Black friends to ask them how you should help.

“It is not my responsibility, or the responsibility of any Black person to inform you, educate you or teach you how to be an ally,” says writer and actor Brandon Kyle Good in a video titled ‘To my white friends: becoming an ally’.

“As you can imagine there is a large breadth of resources and materials and information about our experiences, and about racism and racist tendencies and white fragility out there. I encourage you, I beg of you… honestly, I demand of you, to do the research – do the work. To be an effective ally it takes work. It will be challenging and painful and arduous at times, but it’s necessary. Lives are dependent on your commitment.”

From a workplace perspective, before calling in a D&I expert, it’s worth the organisation taking its first steps on its own. Bringing in a D&I consultant is too often done as a Bandaid solution. Profound cultural change requires commitment no outsider can give you.

Corporate advocacy can have powerful benefits for a business, but it’s important to identify the right times to speak up. Effective allies will spend time learning and listening and only jump in when what they’re saying is going to have a positive impact on others.

6. Other things to keep in mind

The following advice has been selected from Mireielle Harper’s now viral Twitter thread, ’10 steps to non-optical allyship’. You can read the full thread here, but here are five of the most salient points:

- Check in with your colleagues, friends and loved ones in the Black community.

- Educate yourself by reading anti-racist works – (here’s The Guardian’s list of books on anti-racism, and here’s a list from Reconciliation Australia of Indigenous Australian memoirs, policies, reports, works of fiction and more).

- Avoid sharing traumatic content, such as images/videos of Black people being abused. This content can increase the dehumanisation of Black people, writes Harper, and it can be triggering and traumatic for those you’re trying to help.

- It’s not about you. “Leave your ego,” writes Harper. Effective allies do not centre their own pain/disbelief/sadness above those in marginalised communities. Be empathetic but discuss your own emotional responses with friends and family.

- Create a long-term support strategy. The recent events may have been a wake up call for some, but these issues have been around for hundreds of years. Harper writes: “How are you going to make a long-term impact? Can you mentor a young person? Can you become a trustee for an organisation that supports the Black community? Could you offer your time to volunteer?”

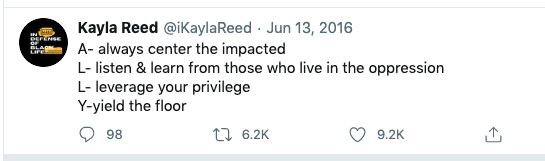

HRM welcomes any additional resources that you’ve come across that you’ve found helpful. Share them in the comments section below. And when in doubt, keep this acronym from Kayla Reed in mind:

List of suggested places to donate: Sisters Inside, Go Fund Me: Justice for David Dungay Junior, Bridging the Gap, Aboriginal Legal Service, Pay the Rent, Black Lives Matter.