AHRI’s latest wellbeing report illuminates the realities of what it’s like to work in human resources amid a pandemic.

Karen Johns has been working around 12 hours more a week than she’s used to over the last few months. As the HR manager at a property firm in Victoria, recent weeks have been a harsh reminder of what she’s already lived through at the start of the year.

“Having enough time to cover the ground to sort out all the new stuff that’s come onto our plate, like JobKeeper and staff wellbeing, has been a big challenge,” she says. “While you’re doing one thing, someone is trying to get you to do something else. You’re being pulled in so many different directions.

“People underestimate how much HR is actually working. We’re at the frontline.”

Johns is one of the 150 people to partake in AHRI’s latest report, ‘COVID-19’s Impact on HR Wellbeing‘ which looks at how HR professionals across Australia have been coping from a wellbeing perspective during what has been the toughest year of many peoples’ lives.

While most respondents reported doing fairly well in their personal lives, the data around their experiences of work is worrying. The massive increase in workloads for HR is taking a toll, as are feelings of disconnection and isolation.

Climbing the mountain (of work)

AHRI’s report shows HR professionals feel they’re constantly chasing their tail – two in three wish they had more hours in the day and 73 per cent say they’re working on tasks that they have neither the time nor energy to complete.

The two researchers behind this report, Dr John Molineux FCPHR, senior lecturer in HRM at Deakin University and Dr. Adam Fraser CSP, human performance researcher, say this is a worrying trend.

“Because HR is such an important function, particularly right now, they get squeezed quite hard. Organisations lean on them quite significantly,” says Fraser.

There’s no sign of things slowing down anytime soon, so one way for HR to manage their workloads, they say, is to strategically prioritise their work.

Fraser says: “You can easily just dump things on peoples’ desks without having a comprehension of how much they already have on. I do this sometimes, but my staff are really good at saying, “if you’re giving me this new thing to do, what am I dropping?’ And that makes me reassess what I really need them to get done.”

Molineux was an HR manager himself for many years, so he knows the pressures of balancing what’s best for both the business and employees more than most.

“It’s already a dichotomous relationship, so it only makes it more complicated when you have your own feelings to manage. It can easily build up and become overwhelming.”

This is why it’s so important to set boundaries, he says.

“HR managers get interrupted so often by spot fires that come up. Instead of taking on that burden themselves, they need to be putting that back on the people who have the problem and coaching them to solve it themselves.

“HR should only be getting involved in the really tough cases, not the everyday stuff – coach the managers to do that.”

Fraser adds that it’s all too common for people to take an ‘HR will solve this for me’ mindset.

“HR has to be careful of enabling and encouraging that behaviour. Learn to push back rather than just rescuing them all the time,” he says.

The edge of burnout

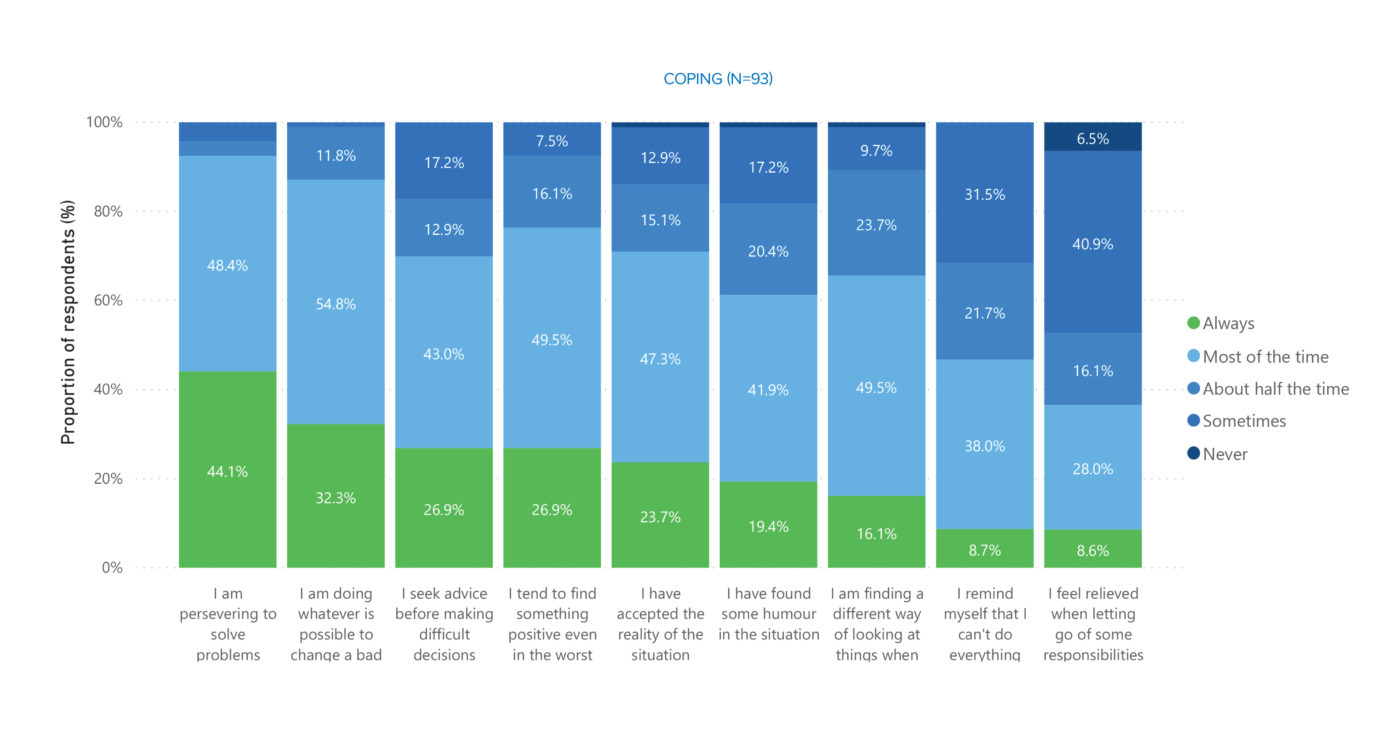

While many respondents are reporting that they’re coping okay (see graph below), what worries Fraser is the subtle indicators of the struggles to come.

“But my biggest concern is what happens in November and December this year because they’re already starting to show the first signs of burnout, like feeling tired for no reason or saying they’re not as happy in their job. These are warning signs around sustainability for the rest of this year.”

Also, the fact respondents felt nervous (23.5 per cent), depressed (13 per cent), hopeless (11 per cent) and that everything was an effort (27 per cent) for either half or most of the time over the last few months shouldn’t be overlooked. Those statistics could easily jump.

In the early days of the pandemic, many of us were running on adrenaline. We had this idea that things would clear up come June/July (and they did, momentarily), so we were able to pull ourselves up from the bootstraps and get on with things.

But with what’s happening in Victoria right now – and with NSW sitting on the knife’s edge – many people are finding their resilience reserve is running low. This is particularly pertinent for HR professionals.

“In those first few weeks of lockdown [in March] the thought was that we’d just hunker down for four weeks and push through it,” says Fraser. “What we’re seeing now is that there seems to be no end to this.

“That uncertainty is incredibly exhausting. People are going to have to change their coping strategies this time around because this might be our reality for quite a while, so we need to think about managing our recovery.”

Johns says: “I’ve found that I’m just so tired, rather than suffering any mental health issues. I’ve just gone through two weeks of reviews with about 60 per cent of the business, so fatigue is my main issue. Trying to stay on and focused is hard at times.”

Molineux says while his previous research suggests HR professionals are a particularly resilient group, he warns that everyone has a tipping point.

To ensure they don’t fall victim to burnout, Molineux and Fraser emphasise the importance of HR professionals practicing self-care consistently. This, they say, is the key to making it through the year.

(To find out more about this, you can read HRM’s HR guide to self-care which includes a helpful template from Black Dog Institute).

Supporting the supporters

More than one in three respondents reported their organisations having to make the tough decision to stand down or make redundant a portion of their workforce over the last few months. This was more common in organisations with over 500 staff (43 per cent) than smaller organisations (34 per cent).

While conversations like this would be devastating for the employee losing their job, it’s also important we spare a thought for the HR practitioners tasked with delivering the news – they’re often having back-to-back meetings relaying this news to multiple people – that’s going to take a toll on their own mental health.

Also, HR are used to being the ones who check in on people, so often they’re left in the shadows themselves. Those executive leaders who take initiative can do the world of good.

“One of our managing directors from a different state recently did a ring around to do a welfare check,” says Johns. “And he called me to ask how I was going and I told him, ‘not many people ask me that.'”

Johns isn’t the only one benefitting from proactive management. AHRI’s data shows many HR professionals are receiving adequate support from their supervisors. Forty-six percent strongly agree that their supervisor is concerned about their welfare and over half say they definitely have access to wellbeing support. However, not everyone is in such a position.

Putting up your hand to signal you’re not coping well with your workload or work in general doesn’t feel like an option for many.

“You can’t always go to your CEO and say ‘I’m feeling overwhelmed and I’m second guessing everything.’ That’s not a message they always want to hear,” says Fraser.

If there are murmurs of redundancies on the horizon, for example, some people might fear their head will be next on the chopping block if they’re honest about not coping. A safer option, they might feel, is to stay quiet and continue just scraping by.

So if talking to their manager isn’t an option, where should they go? Perhaps it’s best to think of it in terms of the way psychologists approach their own mental wellbeing. It’s mandatory that each psychologist in Australia is allocated a supervisor to meet with on a regular basis. Ideally, this person is not their manager – it’s someone they can talk to about their client’s issues and their own wellbeing, as well as someone to seek guidance from.

Organisations could make a rule that each HR professional in their workplace had someone to seek counsel from who was separate from their regular team.

“That might be someone you access through AHRI or your own network. You just need to have someone to debrief with,” says Fraser.

Generation lonely

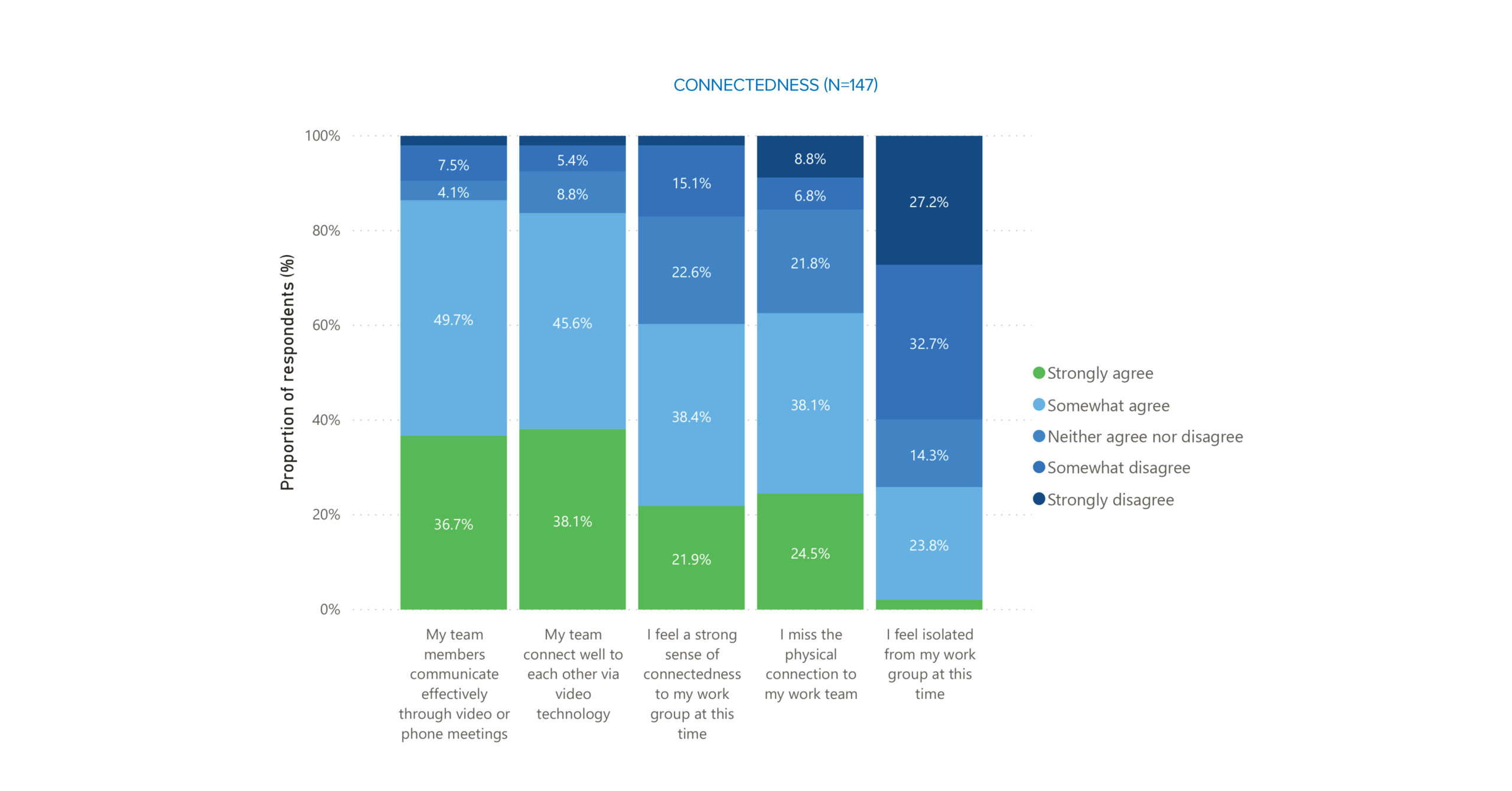

A particularly troubling finding from AHRI’s report is the amount of HR professionals who report they are struggling with the loss of physical connection to their team. One quarter reported feeling “completely isolated from their regular work groups”.

As HRM previously reported, the psychological impacts of isolation can be dire. Feeling isolated can cause negative shifts in our mood impact our sleep and has been linked with increased prevalence to disease and even early death.

But staying connected with one another in 2020 is no easy task. Even though the uptake of virtual socialising through video calls has skyrocketed, many people are lonelier than ever. In the workplace, this can’t just be on HR to fix as they’re experiencing it themselves.

More than four in five respondents reported that communication and connectedness through virtual platforms has been a success in their organisations, yet 62 per cent say they’re struggling with feelings of disconnection.

These two statistics might appear to contradict each other, but there’s a huge difference between the emotional impact of a Zoom call and the deep, nourishing social connectedness gained from a face-to-face meeting.

Molineux suggests HR might be feeling this harder than other industries due to the nature of their work.

“Most HR professionals are ‘people’ people. I know of HR professionals who hardly get any work done in the day because they’re busy building relationships; they do their own work later on. I can imagine that people who aren’t getting to walk about and touch base with people [in person] would be really missing it.”

It’s important to be realistic about the future. It’s going to be an uphill battle, but it’s not without hope. Even though the light at the end of the tunnel has moved further away, it’s still there. In the meantime, HR professionals need to take a long-term approach to their wellbeing.

Johns’ approach to get through the next few months is to practice gratitude as much as possible.

“I’m still working. I live in a reasonably nice house. I’m safe. I’ve got food. So I try to be thankful for what I do have. That’s certainly helped me to get through the recent restrictions.”

This only touches on some of the insights from AHRI’s Wellbeing report. To find out more, you can download the report here.

I get frustrated when AHRI leaders such as Dr John Molineux argue “HR should only be getting involved in the really tough cases, not the everyday stuff – coach the managers to do that.” As a profession we have been saying the same thing for at least 40 years. Let’s stop blaming managers and see what we can change. In my experience it’s the following. 1. Simplify the HR systems and processes we insist line managers user. They are currently too complex. 2. Shift our focus to managing risk. Too often we insist on managing just the process. When managers… Read more »

In line with Mark’s feedback – yes, we are coaching and empowering Managers to look after the “everyday stuff”. That’s what we’re doing day in day out. And refining the tools and procedures to do so. Funnily enough it takes more resources than actually managing those matters ourselves. We may be building capability but it’s an ongoing and evolving area. HR leaders coach others on managing workloads, setting reasonable expectations and boundaries, and work/life integration. The survey results would tend to indicate maybe our subject matter expertise in this area is merely theoretical.