HRM looks at research on our biases about older workers – from why conversations about ageism tend to focus on the elderly, to the troubling implications of ‘compassionate ageism’.

Quick thought experiment: you have two employees with the same role. One is 34, the other is 57. Knowing nothing else, who would you spend your training budget on?

Despite the fact that the national average tenure for people between 25-35 is less than three years, and the average tenure of those aged over 45 is almost seven years, you can imagine most people elect to train the younger person.

Ageism might be the silliest prejudice, if for no other reason than the fact that, if we’re lucky, we will all eventually experience being both young and old. You’d think that some form of self-interest, if not empathy, would prevent workplace discrimination based on age. But apparently humanity is too complex for such a one-to-one equation.

To help deconstruct the bias against the older aspect of ageism, here are four facts to keep in mind.

1. There are good reasons to focus on older workers

When most people think of ageism, they tend to only picture harmful stereotypes of older people – even though it encompasses any bias based on age. Surprisingly, there are sensible reasons why that is the case.

As explained in the SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Psychology, though both younger and older workers face discrimination because of their age, researchers have focussed more on the latter because (among other things):

- Studies show older workers are more willing to quit when they percieve ageist discrimination

- Studies show everyday discrimination affected the job satisfaction of both older and younger workers, but only older workers also experienced a negative impact on their general psychological wellbeing

Of course, that doesn’t mean we should not tackle discrimination against younger employees. But it’s worth keeping in mind that ageism against older workers, at least according to current research, is harmful in ways that ageism against younger workers isn’t.

2. Ageism begets ageism

Another interesting fact from the SAGE Handbook of Applied Social Psychology: research has shown that there is a bias against older workers because of a fear that they will retire soon (even earlier than the retirement age). Relatedly, other studies show that an ageist workplace causes older workers to retire earlier.

So a workplace that discriminates against older workers could very well view its discrimination as justified – but it would be confusing the effect and the cause. There is a vicious stereotyping cycle going on here.

Want to find out more fascinating facts about the world of HR and connect with like-minded professionals? The 2019 AHRI National Convention and Exhibition is the place for you. Hurry and register now as signup closes this Friday.

3. Compassionate ageism is a thing

In discussions of discrimination, we tend to think of negative stereotypes – those with no redeeming elements. But researchers have long looked into discrimination of a more subtle sort: ambivalent stereotypes. This is where negative impressions towards a particular group are balanced with positive impressions.

Often this split tracks the difference between our feelings and our esteem. For example, while people might feel negatively about the very wealthy (seeing them as self-interested, greedy, and so on) they will also often believe they are powerful.

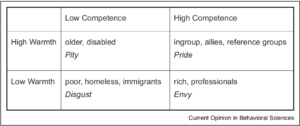

Princeton University researcher Susan Fiske, in her paper Intergroup biases, offers a good explanation of a stereotype content model (one she helped develop) that tracks this: it looks at warmth and competence.

“Warmth reflects the other’s intent, so it is primary and arguably judged faster. Competence reflects the others ability to enact that intent, so it is secondary and judged more slowly. The most valid traits reflecting warmth include seeming trustworthy and friendly, plus sociable and well intentioned. Competence includes seeming capable and skilled.”

When it comes to older people, researchers Amy Cuddy, Michael Norton, and Fiske found that “pity is the main emotion uniquely directed to this group”. We tend to have nice feelings about the older generations, but don’t view them as capable.

Source: Susan Fiske, Princeton, in her paper Intergroup biases

Source: Susan Fiske, Princeton, in her paper Intergroup biases

The same study also found:

- “Apparently, the negative aspect of the elderly stereotype (incompetence) resists change, while the positive aspect of the elderly stereotype (warmth) is more malleable.”

- “Elderly targets who behaved more incompetently gained in warmth, indicating that the highly incompetent target was rewarded on his group’s positive stereotype (warm) for behaving consistently with his group’s negative stereotype (competent).”

- “It is difficult for an individual elderly person to override the warm and incompetent stereotype via stereotype-inconsistent behavior”.

The research reveals how ageism presents unique challenges.

Apply the above findings to the workplace and imagine two HR professionals conducting a job interview with an older woman. They would notice that they have nice feelings about her at the same time as being sceptical as to her capability. Ticking off her relevant experience is apparently not likely to remove that scepticism. And anything that operates against her – say she accidentally misspoke, or forgot something – would make them like her more, because it would fit the stereotype they had of her.

They would leave the interview convinced they’re not being discriminatory – how could they be when they have such warm feelings towards her? They might even tell colleagues “I really wish we could hire her, but…”

This brings us to the last point.

4. Think you’re immune to bias? You are wrong

The two essential things you have to remember about biases is that we all have them, and we all have a very hard time discerning to what extent they’re informing our decisions.

Indeed, one sure way to make sure you will be unfair is to think you’re incapable of doing so. If you define yourself as someone who is free from prejudice, you will examine your prejudices and see only reasonable logic.

You might look at the workforce you hired and see that nobody is aged over 50. But you won’t think, “Ah crap. Time to do something about that bias of mine.” You will tell yourself things like, “the older candidates we talked to weren’t the right fit”; “seems older people don’t want to work in this industry”; or “older workers aren’t capable of handling our sophisticated systems”.

And if a couple of workers do happen to be aged over 50, you will give yourself a pat on the back for your progressive mindset. You won’t wonder whether that percentage is representative of the wider population.

Because compassionate ageism is a factor, people who are engaged in diversity and inclusion in this space also have to be watchful to make sure they aren’t inadvertently supporting a stereotype. HRM has been guilty of this error. In 2018, in an article about overcoming ageism, we wrote, “If older workers are failing to upskill, it could be that they aren’t afforded the same training opportunities as younger employees.”

The statement means well – it’s trying to say that there is a tendency to not train older workers and then blame them for a lack of training. But what it’s actually saying is “in some cases where older workers fail to learn, it is not their fault”, which implies that the rest of the time it is their fault and it’s because they’re older.

A better formulation would have been, “There is a bias that older workers have trouble upskilling. There is no real evidence that’s the case. In fact, if you think you’ve seen proof in your own organisation, what you could be seeing is the outcome of the bias. Because often older workers are not afforded the same training opportunities as younger employees.”

Even the headline of this well-received article on ageism, “How to nurture an ageing workforce” carries with it implications of frailty, and therefore sounds a little too close to compassionate ageism.

The key takeaway is this: Sad as it is, having your heart in the right place is not enough to overcome a bias.

One of my best workers is also the oldest in my team. Don’t underestimate the benefits of diversity of age in your team! Hiring based on any stereotype is just leaving great employees for those of us who are willing to challenge those biases.