Just a month after cosmetics giant Mecca was named one of the best places to work for 2019, staff have called out a toxic culture of bullying and mistreatment.

Just last week we highlighted the Great Place to Work’s (GPTW) list of top employers of 2019. Coming in 4th on the list of employers with over 1,000 staff was million dollar cosmetics company Mecca. But news has emerged this week which proves that such lists might not be all they’re cracked up to be.

A string of former and current employees of Mecca have come out of the woodwork to reveal a culture of discrimination, favouritism and bullying. How can a company with an apparently rampant culture of mistreatment be named one of the best companies to work for? And not just once, but for the sixth year in a row?

Although the weighting of the GPTW list is reportedly taking into account staff’s responses to a 58 question survey, which accounts for two thirds of the decision, it perhaps doesn’t have any protection against a culture that would dissuade employees from answering truthfully.

And media organisations (ourselves included) aren’t helping by holding these lists to such a high esteem.

No amount of concealer can cover this up

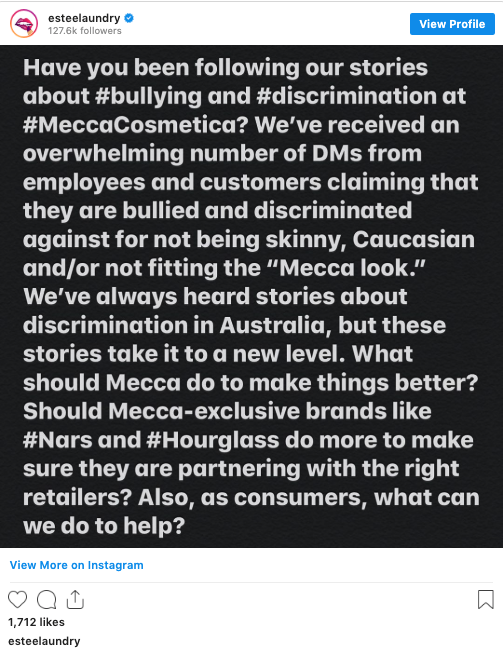

An anonymous Instagram account, @Esteelaundry, was the first platform to start collecting complaints from staff and, according to the Sydney Morning Herald, more than 50 complaints have been made so far, ranging from claims of racism to a “toxic culture of favouritism and nepotism”. And according to reports from Pedestrian TV, the Young Workers Centre Victoria has received 14 written complaints from both former and current staff.

An Instagram story shared on the account told the story of a former employee, who chose to remain anonymous, who says they worked for the company for three years and were “fully under their spell”.

“My manager did some really dodgy sh*t, like just not giving people their allocated breaks, giving sh*tty testers as a present to skip your break, or not paying people for the breaks they were entitled to which was hushed… and sorted [out] internally.

“I postponed having a laparoscopy I desperately needed because [Mecca was] expected to be busy. When I was diagnosed with [endometriosis] they were incredibly unsupportive and made me feel like I was a lesser employee for having an illness. I was told to “leave it at the door” multiple times and [they said] if I couldn’t be “110%” not to come in… [They had] absolutely no tolerance for chronic illness. Eventually, I was forced to resign because I couldn’t fulfil my previous part-time [role].”

Another anonymous employee told Seven News she had nightmares about work. She also backed up the allegations made above that the company had low tolerance when employees were sick, claiming they would use language that “shamed” employees if they called in sick. If she was unwell, she was scared to message her manager for fear her shifts would be cut.

“I also heard stories of friends who would go home and cry after shifts because a manager was aggressive and made them feel embarrassed,” she says.

While anonymous claims often need to be taken with a grain of salt, the huge number of them should be deeply alarming to everyone. Not to mention, some staff were willing to speak on the record.

Speaking with the Sydney Morning Herald, former employee Narita Salima said after a few weeks of working there, she realised that the company culture that Mecca portrays to the public is “just so fake”.

After being bullied and bringing this to her manager’s attention, Salima was fired. She described the situation as “traumatic”.

Mecca is left blushing

Mecca’s founder, Jo Horgan, sent out a letter to staff promising to do better, stating that action would be taken to investigate all claims. She also stated she was “surprised” by the concerns, and claimed only 0.2 per cent of Mecca staff had made a formal bullying complaint over the last two years.

What Horgan is perhaps missing here is the fact that a lack of complaints doesn’t equal a lack of reasons to complain. In fact, you could almost argue that such a low number of complaints is unhealthy, and probably a worrying sign for an organisation’s complaint management system, its culture, or both. AHRI recently released a report on this very topic. One of the key findings to come from the 5 hard truths about workplace culture report, was that CEOs often wear rose-coloured glasses when it comes to the realities of their workplace cultures.

“This further emphasises the important, albeit at times courageous, role HR needs to play in making sure the metrics as they relate to a sustainable culture are carefully considered across both financial and non-financial areas over which HR has oversight,” says Rosemary Guyatt the Australian Human Resource Institute’s general manager of people and culture.

A complaint rate of less than 1 per cent is actually reason for concern. This is only further amplified by the fact that an anonymous Instagram account was the chosen platform for staff to share their problems, again, anonymously.

Employee grievances are part and parcel of work, and a culture that allows people to come forward and share their concerns without fear is a feature of a company that’s doing things right.

“While someone can say, ‘we’ve got a low level of complaints’, that doesn’t accurately reflect the culture of feedback that they have,” says Guyatt.

In Mecca’s online newsroom, there is a response to the controversy (ironically, it sits right above its announcement that it graced this year’s Great Place to Work list – go figure).

The statement reads: “For the past 22 years, our mission has been to go above and beyond to ensure all our team members have a positive experience. To anyone for whom this hasn’t been the case, we’re truly sorry.

“MECCA has grown exponentially in the last five years and we acknowledge that, despite all of our best endeavours, our culture may have been tested.”

In the statement, the company claims to have zero tolerance for bullying and has taken the following steps to address the concerns:

- An external service called STOPLINE has been introduced for staff who wish to anonymously share their complaints.

- An external HR consultancy has stepped in to conduct what’s being referred to as a “listening tour” (a staff consultation) and will make recommendations to Mecca.

- Most staff are said to be undergoing ‘Respect in the workplace’ training which includes modules on diversity and inclusion and bullying and harassment.

“I wonder what the people and culture priorities [of Mecca] were prior to this controversy?” Guyatt points out.

What Horgan is perhaps missing here is the fact that a lack of complaints doesn’t equal a lack of reasons to complain. In fact, you could almost argue that such a low number of complaints is unhealthy, and probably a worrying sign for an organisation’s complaint management system, its culture, or both.

So, how do you actually determine a good workplace?

In the GPTW 2019 report, Mecca was highlighted for continuing to “live by their commitment to helping Australia’s women look and feel their best.” This may be true for its customers, but it doesn’t seem like the same can be said for its staff.

In the 2018 GPTW report, there was a strong focus on Mecca’s company culture of staff being “considerate” of each other and “friendly smiles from the leadership team when passing by”.

It’s all well and good to say these are your company values in an award submission, but it’s another thing to live them on a day to day basis. Guyatt likened applying for these awards to applying for a job.

“Companies that apply for these awards programs often pay to be involved. In this case, I’m sure the program has some structure and a level of reference checking, but just like applying for a job, people are only going to put down referees who are going to provide a positive response.

“Reference checking for these awards does need to be broader, and checking social media can help,” says Guyatt.

AHRI has its own awards program and Guyatt says they’ve had similar scenarios where an organisation or individual has applied and then was found to have a troubling past. By doing a thorough reference check, Guyatt says AHRI was able to identify this and take the matter seriously.

“You have to look beyond what’s stated in the application,” she says.

Guyatt suggests that when determining who makes these lists, we should look at other metrics like turnover and retention rates, employee’s development and progression opportunities as well as what they’re saying when they leave an organisation.

“If we’re going to say somewhere is ‘the best place to work’ we really need to be able to have a multidimensional view of it – internally and externally. I’m sure there are many great places to work that, for whatever reason, don’t make it on this list,” says Guyatt.

If these allegations are proved to be true, should Great Place to Work Australia remove Mecca from its list? Tell us what you think in the comment section below.

Challenges are present in any working environment and it’s important that leaders are well versed in how to communicate this to their people. Ignition Training’s ‘Having Difficult Conversations one day course can help you to effectively communicate to staff during tough times.

Considering you have to pay a fee to be considered for the ‘Top Places To Work’ list, I can’t see why anyone would think it’s credible.

I find most of these awards are flawed and the publicity machines are part of the problem. For example, people write a book get a bunch of people to buy a copy at .99 cents to get it on the best seller list. All of a sudden they are a best selling author and radio shows contact them for their amazing insights. Meanwhile other’s in their industry are truly doing amazing things and do not have the time to write a mediocre book, spend time on radio shows and at big events to promote themselves. I believe we need to… Read more »

Thank you for writing this article. I so resonate with this after working in so many companies- small & large. It’s all the same. I’m shocked to read this, but not shocked that employees don’t come forward for fear of loosing their job. I am a Mecca customer & after reading this, I don’t want to be anymore! That’s not how their staff should be treated & it stops & starts with their leaders! Winning Employee choice Awards gives no meaning if you only ask those that are favourites or are in the “in crowd”! Total lies & mistruths. I… Read more »