Australian union membership has been in decline since the 70s. A new report attempts to track trends and establish where and why this has happened.

Though a few unions have actually managed to increase their membership (including the Police Federation and Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation), the overall number of Australians in unions has been dropping for decades. In 1976 just over 50 per cent of all employees claimed membership, now that number sits at 14 per cent.

A new parliamentary report on the changes attempts to answer the where and why of that trend.

Why union membership is declining

As for the ‘why’ of union decline, the report suggests the following factors:

- Increase in part-time and casual employment and a decrease in full-time employment

- The end of compulsory membership, due to federal and state legislation in in the eighties and nineties

- The decline of industries with traditionally high membership, such as car manufacturing; printing and textile; and clothing and footwear

- Growth in service industries that have always had low membership

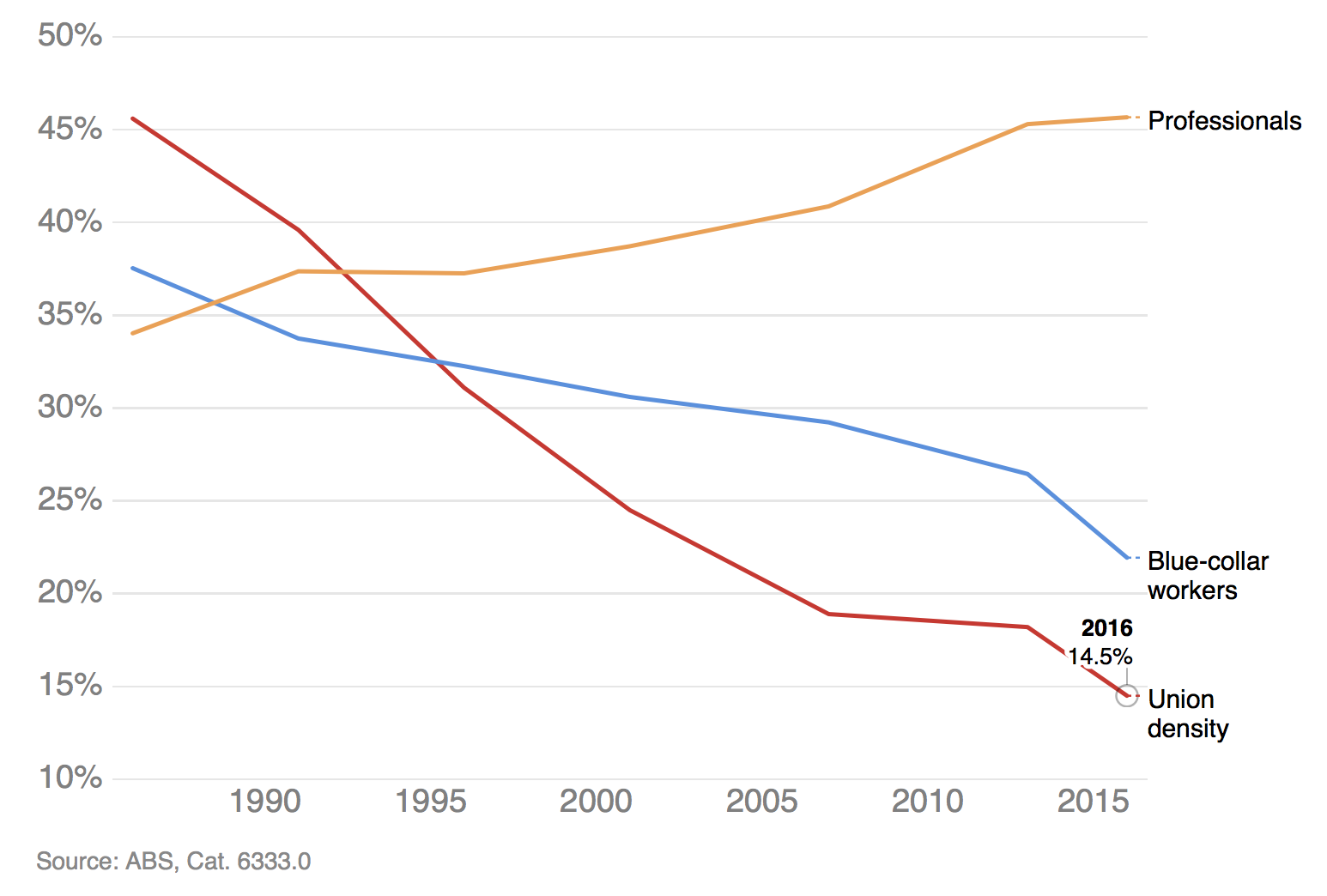

Those last two points are elegantly captured in this graph (sourced from Griffith Business University Professor Bradley Bowden article on the Conversation).

Job type

In terms of how the type of work people are engaged in has an impact on union membership, having paid leave seems like the most significant variable. The report says that twenty per cent of those who had paid leave are union members, compared to 5.6 per cent for those who don’t.

There is a smaller difference between those working full-time (15 per cent) and those working part-time (11 per cent).

Demographics

It might seem surprising, but there’s a slightly higher union density among women (16 per cent in 2016, from 35 per cent in 1992) than there is men (13 per cent, down from 43 per cent in 1992). Apparently this is partly due to women being in more unionised occupations such as nursing and teaching.

This fits with 2016 data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics, which showed that the top three industries for women were hospitals, primary education, and aged care residential services. For men they were computer system design and related services, cafes and restaurants, and supermarket and grocery stores.

Older workers are much more likely to be union members compared to their younger counterparts:

- Workers aged 45-64, 19 per cent union membership

- Workers aged 25-44, 13 per cent union membership

- Workers aged 15-24, six per cent union membership

According to the report, “one of the major reasons for lower union membership among young people is they are much more likely to be working on a casual and/or part–time basis compared to older workers.”

But while different work types undoubtedly have an impact, this seems like a limited explanation. Certainly it applies to 15-24 year olds, but what about the six per cent difference in union membership for the two older groups? Rates of part-time work between those groups aren’t so different.

Overseas comparisons

According to OECD statistics, the developed countries that have experienced comparatively similar union membership declines to Australia are New Zealand and the UK. The former had 69.1 per cent union membership in 1980 and 17.7 per cent in 2016. The latter saw a drop from 52.2 per cent to 23.7 per cent in the same period.

But a Commonwealth country that has had a different experience is Canada. According to survey data, they had 33.4 per cent union membership in 1990 and 26.3 per cent in 2016.

One of the biggest reasons for the difference between countries is legislation. An OECD report on employment notes: “The last decades have shown that in many cases the alternative to collective bargaining is not individual bargaining, but either state regulation or no bargaining at all – as only few employees can effectively negotiate their terms of employment with their employer.”

But regardless of individual differences, the overall trend in developed countries is towards less union membership. As the OECD report found: “Since the 1980s, [the] process of collective representation and negotiation has faced a series of major challenges resulting, in particular, from technological and organisational changes, globalisation, the decline of the manufacturing sector, new forms of work and population ageing, which have severely tested its efficacy.”

Learn about recruitment strategies as well as current legislation and labour conventions that underpins practice, in the AHRI short course ‘Recruitment and workplace relations’.

How about the ROI in union membership is, for most employees, zero? Last time my employer negotiated an agreement. The relevant union (remember unlike most consumer goods, your union is a monopoly, due to demarcation rules) never sent an organiser to a single bargaining session, delayed bargaining for almost half-a-year by having no organiser for delegates to consult with, told delegates that were legally nominated as bargaining agents by both union and non-union employees that they could only represent union employees, over the course of 2 years provided 4 different organisers requiring delegates to constantly have to bring the new… Read more »

Maybe union membership is in decline due to unions being weak and not actually helping employee.i know if my union was any good I would not have been forcibly transferred from govt to private employment. They seemed powerless to change one single thing but they did spread propaganda to employees to get support but still nothing changed. I also see them supporting people that helps them to make a political gain. I could have negotiated better by myself

While I’ve always been an advocate for the importance and place for Unions in the workplace (alongside a great HR team of course!), I would like to think that employers are recognising the importance of employees in achieving their goals and engage and communicate with their teams to help ensure the right environment, alongside sustainable benefits and conditions are introduced to see an organisation’s resulting high-performance and positive culture deliver the outcomes the organisation needs for success and its own sustainability. One angle to a complex puzzle – and maybe its just that I’m an optimist.

In 2018 the Productivity Commission reported that the economy needed wages growth. On one basis, there is a demand problem in the economy with the decline in real wages and a greater % of household income being spent on necessities.

If you have poor outcomes, what is the system that delivered those outcomes? The national wage case is reliant on union involvement; yet union representation is now? Economic or structural Policy change? And where is the Senate in all this?